EAGLE PASS, Tex. — Seek to end birthright citizenship for children of undocumented immigrants. Keep asylum seekers in Mexico while their American court cases pend. Finish the border wall — and use “deadly force” against some people trying to break through it and bring drugs into the United States.

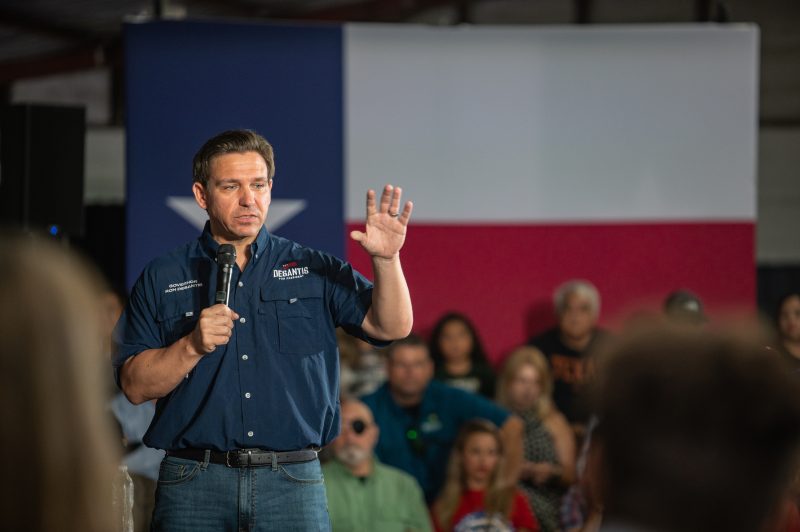

Ron DeSantis on Monday laid out a sweeping plan to restrict immigration at the southern border that reflects his fundamental pitch for the presidency: The Florida governor says he will deliver the ideology of Donald Trump with better follow-through, including by attempting some measures likely to face stiff legal challenges. Trump’s campaign immediately countered with accusations that DeSantis is “copying and pasting” his agenda.

DeSantis’s proposals include “rules of engagement” enabling U.S. personnel to kill certain people breaking through the border wall. He said deadly force would “of course” be justified against people carrying drugs and showing “hostile intent” but did not spell out exactly what that meant.

“If you go, if you drop a couple of these cartel operatives trying to do that, you’re not going to have to worry about that anymore,” DeSantis told reporters. Earlier, in a speech, he compared the border to a home invasion.

“If someone was breaking into your house, you would repel them with the use of force, right?” DeSantis said. “But yet if they have drugs, these backpacks, and they’re going in and they’re cutting through an enforced structure, we’re just supposed to let ’em in? You know, I say use force to repel them. If you do that one time, they will never do that again.”

Under U.S. law, authorities are empowered to arrest and prosecute individuals who have attempted to saw through or damage the border wall. Customs and Border Protection says deadly force is justified when someone poses an imminent threat of death or “serious” physical injury to another person.

The immigration plan, which DeSantis announced near the southern border here, marked a shift for a candidate who for months has focused heavily on promoting his record in Florida and using it as a blueprint for governing on a larger scale. A month into an official campaign launch that has yet to dent Trump’s dominance in the polls, and amid some criticism of his campaign’s stagnation, DeSantis is starting to roll out national policy proposals, beginning this week with an issue core to Trump’s political identity.

His pivot will include proposals on the economy, crime and combating what Trump first derided as a “deep state” in the federal bureaucracy opposed to his agenda.

DeSantis has started to highlight some policy differences with Trump, criticizing the former president from the right on crime, abortion and the federal government’s response to the coronavirus pandemic. But on other issues, such as immigration, he is trying to draw a different contrast, saying he will follow through on promises that Trump never carried out.

“I have listened to people in D.C. for years and years and years … Republicans and Democrats always chirping about this and yet never actually bringing the issue to a conclusion,” DeSantis said Monday morning, speaking between large banners reading “No excuses.” He added, “We don’t want hollow rhetoric.”

Trump has previously floated the use of force against migrants, telling aides that he wanted U.S. forces to block people from crossing the border with bayonets and suggesting a moat filled with dangerous reptiles, officials familiar with his comments told The Post in 2019.

“If the cartels are cutting through the border wall, trying to run product into this country, they’re going to end up stone-cold dead as a result of that bad decision,” DeSantis told reporters.

Immigration and border security continue to be important issues for Republican primary voters, whom Trump energized with his hard-line proposals when he first ran for president. It remains to be seen whether DeSantis can peel away GOP voters still largely loyal to the former president — and often inclined to blame Trump’s enemies for gaps between his campaign promises and his accomplishments in office. The Florida governor is running a distant second to Trump after losing ground this spring, and he hasn’t gotten a bump from his official launch, at least in national polling.

“One time you can really move the needle is when you launch your campaign,” and DeSantis’s kickoff “failed to spark momentum,” said Alex Conant, the former communications director for Republican Sen. Marco Rubio’s 2016 presidential campaign.

It is unclear whether some of what DeSantis is proposing is possible, because it would mean challenging rights explicitly granted in the U.S. Constitution. Birthright citizenship is enshrined in the 14th Amendment.

Some Republican rivals have criticized DeSantis as a Trump copycat: “America deserves a choice, not an echo,” one video from presidential candidate Nikki Haley argued. But Haley and the many other Republicans marketing themselves as more distinct alternatives have yet to break double digits in polling in a primary that still revolves heavily around Trump.

Speaking in front of a barbed-wire fence along the Rio Grande, DeSantis said of Trump, “I think a lot of the things he’s saying, you know, I agree with, but I also think those are the same things that we said back in 2016.”

“Where we differ on is, you know, we’re more aggressive in terms of our plan than anything he did in empowering local officials to enforce immigration law,” DeSantis said, also listing his plan to “lean in against the drug cartels” as a way he differs from the former president.

DeSantis has spent months touring the country and pitching Florida as a “blueprint,” highlighting his opposition to coronavirus restrictions and his battles over how schools and companies approach gender, sexual orientation and race. He talks about his home state far more than other presidential candidates; “Florida” was the most-used word in his Iowa campaign kickoff speech this month, outside of common conjunctions.

The southern border was a major focus of Trump’s 2016 campaign, during which he promised to build a wall and to make Mexico pay for it — something that DeSantis allies point out he didn’t accomplish. Judges initially blocked Trump’s attempts to fund a border wall without Congress’s approval by declaring a national emergency, but the Supreme Court ruled Trump could proceed with money he diverted from the military. Trump started a wall but didn’t finish it.

Campaigning for a second term, Trump is still touting his border policies as president while denouncing the Biden administration, which has worked to end a Trump-era requirement that asylum seekers stay in Mexico while U.S. courts review their cases. Immigration arrests at the southern border rose after Biden took office and reached their highest levels on record last year, topping 2 million annually.

Trump has vowed to go further on immigration in a second term and seek to end birthright citizenship by executive order on “Day 1,” a move that would face legal challenges. DeSantis’s team has noted that Trump made that promise for many years without following through.

DeSantis’s border plan underscores his similarities to Trump when it comes to policy. Ammar Moussa, a spokesperson for the Democratic National Committee, denounced DeSantis’s plans on Monday as “an echo of the same cruel and callous policies of the Trump administration.”

Like many GOP politicians, DeSantis is sharply critical of the Biden administration and says he will ensure that those who cross the border illegally will be detained until their hearing date. DeSantis’s campaign said Monday in a statement that he will designate Mexican drug cartels as “transnational criminal organizations,” deploy the military to the border and finish a wall there using “every dollar available to him as President.”

DeSantis’s campaign also says he will renew Trump’s controversial push to exclude undocumented immigrants from the census counts used to apportion representation in Congress, which ran into legal challenges and never came to fruition.

Additionally, the governor’s team says he will “close the Flores loophole” that he argues incentivizes human trafficking — apparently referring to a 1997 consent decree called the Flores agreement that says the government must work to quickly release migrant children from detention. A federal judge in 2019 rejected Trump’s proposal to allow indefinite detention of children and their parents.

DeSantis is also promising to cut off “hundreds of millions of dollars in grants” to places that “try to thwart federal immigration law” and declare themselves “sanctuaries” for the undocumented. Trump similarly withheld federal grants.

On birthright citizenship — which grants U.S. citizenship to anyone born on American soil — DeSantis’s campaign argued that it is “inconsistent with the original understanding of the 14th Amendment” and said the governor would “force the courts and Congress to finally address this failed policy.”

DeSantis approved some of the furthest-right immigration legislation in the country this year in the run-up to his campaign, requiring many more private businesses to verify that employees have immigrated legally and mandating that Medicaid-funded hospitals ask about patients’ immigration status.

He also grabbed headlines in the fall by flying undocumented immigrants from Texas to liberal Martha’s Vineyard, drawing condemnations from Democrats and civil rights groups who said migrants were misled.

Frank Junfin, an undecided Republican voter who attended the DeSantis event in Eagle Pass, said it’s important for candidates to come see the border.

“I work in Mexico,” said Junfin, an entomologist in agriculture, “and you know, they’re one of our allies. … I’m so glad he’s here to understand what’s really happening in our border area.”

But he was hesitant about aspects of DeSantis’s plan, such as his campaign’s statement that “if the Mexican government drags its feet, DeSantis will reserve the right to operate across the border to secure our territory from Mexican cartel activities.”

Knowles reported from Washington.