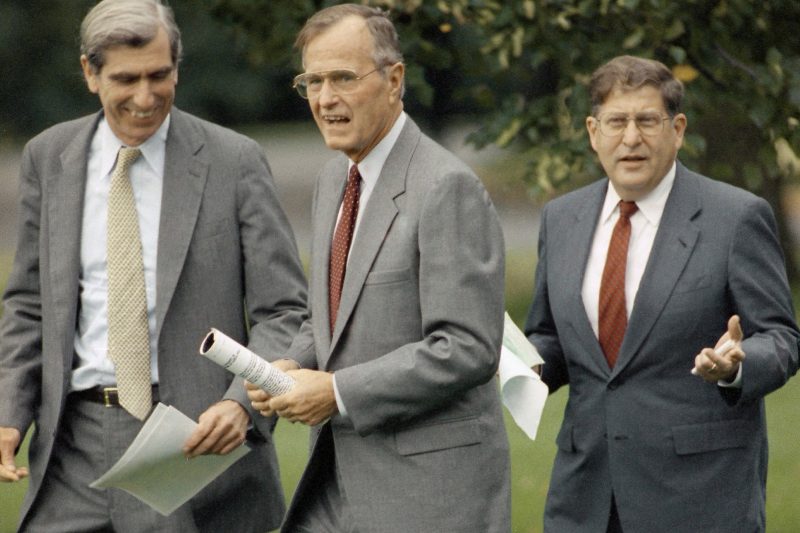

C. Boyden Gray, a patrician conservative lawyer who served as White House counsel to President George H.W. Bush and was influential in shepherding Republican judicial and Justice Department nominees as a strategist and fundraiser, died overnight on May 20 or 21 at his home in Washington. He was 80.

The cause was a heart ailment, said his son-in-law, Nick Summers.

Raised in a North Carolina family steeped in a fortune from banking and tobacco money and communications holdings, Mr. Gray cut a formidable swath in Washington legal and political circles. A lanky 6-foot-6 with thick brows and a reputed inattention to ironing his dress clothes or mending worn shoes, he developed a reputation as a meticulous lawyer and policy maven with workaholic tendencies.

He had been a clerk for Chief Justice Earl Warren, then a leading corporate antitrust lawyer before switching from his family’s ancestral home in the Democratic Party to the Republican side of the aisle. He was swept into the orbit of the incoming Ronald Reagan administration in 1980.

He bonded most closely with Vice President-elect Bush, with whom he shared an Ivy League pedigree and overlapping social connections. Both belonged to the Alibi Club, one of the most exclusive and secretive groups in Washington. Their fathers had once been golfing partners.

Mr. Gray became Bush’s counsel and deputy chief of staff and mostly was known for his work overseeing day-to-day operations of the presidential task force recommending the slashing of government regulations on trade, energy, agriculture, automobiles, prescription drugs, banking, and the environment.

Because of Mr. Gray’s corporate background, his work on the task force was greeted with immense skepticism from consumer advocates. He was persuaded, however, not to weaken disability-related regulations.

Mr. Gray was legal counsel on Bush’s presidential campaign in 1988 and was rewarded with the position of White House counsel after Bush defeated Democratic nominee Michael Dukakis, the Massachusetts governor.

His initial transition into the job was complicated by political missteps. In addition to providing legal advice to the president and the White House staff, one of the major functions of chief counsel was overseeing strict ethics compliance with rules directed at the executive branch.

He drew criticism for remaining on the board of his family’s communications company during his years working for the vice president and also for being slow to place his vast wealth into a blind trust. While not technically required of someone on the vice president’s staff, it was an easy point of political attack against the new Bush administration for someone charged with policing ethics rules.

Mr. Gray was also said to have given his approval to the nomination of John G. Tower as defense secretary, despite the former Texas senator’s long-standing reputation as a womanizing alcoholic and his close relations with defense contractors. The defeat of the nomination in the Senate, less than two months into the new administration, marked the first time in decades that a president had been denied a Cabinet choice. (Tower was killed in a plane crash in 1991.)

On palpable display within the White House were growing tensions with Secretary of State James A. Baker III, long one of Bush’s most intimate advisers. As his own portfolio of holdings drew scrutiny — he resigned as chairman of a family corporation — Mr. Gray reportedly leaked to the media that Baker had ample stock in a bank holding loans to developing countries, which could be a potential conflict of interest. Baker soon unloaded his stock.

The Baker-Gray rift never fully healed, and Bush continued to express faith in both men. Mr. Gray continued as chief counsel and helped negotiate amendments to the Clean Air Act in 1990. Three years later, he returned to a partnership at his longtime white-shoe firm, Wilmer, Cutler & Pickering, to continued work in regulatory law and as a lobbyist for major corporate clients such as Microsoft.

President George W. Bush, the son of his political mentor, named Mr. Gray to a recess appointment as ambassador to the European Union in 2006. After almost two years in the position, Mr. Gray finished out the Bush administration’s second term, first as special envoy for European affairs and then special envoy for Eurasian energy.

Meanwhile, Mr. Gray was especially active in right-wing political organizations such as FreedomWorks, which seeks lower taxes and less regulation, and the Federalist Society, a networking group for conservative lawyers. He also helped to start the Committee for Justice, a nonprofit that screens judicial and Justice Department nominees.

He became involved in the judicial nomination fight early in the George W. Bush administration when Sen. Trent Lott (R-Miss.) grew irate after Democrats on the Senate Judiciary Committee in 2002 blocked a conservative Mississippi trial judge, Charles W. Pickering Sr., from a seat on a federal appeals court. Like Lott, Mr. Gray was furious about filibustering of federal judgeship nominations and worked to end the process.

Although executives and corporations had long sought to avoid entanglement in legal confirmations, Mr. Gray persuaded the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and others to open their coffers in nomination battles because the political flavor of the nominee might affect the outcome of costly class-action lawsuits. Mr. Gray got George H.W. Bush to host a cocktail party at his Houston home that hauled in $250,000 for the cause, The Washington Post reported.

The Committee for Justice took a page from liberal interest groups like People for the American Way in its extensive outreach effort to journalists and activists. To address Democratic opposition in the Senate to the 2005 federal appeals court nomination of William H. Pryor Jr., who was known for his harsh views on abortion and gay rights, the Committee for Justice took out a newspaper advertisement claiming “Catholics Need Not Apply” for court appointments.

“Boyden Gray has always represented well the interests of the Bush family and the corporate community,” Ralph G. Neas, then president of People for the American Way, told The Post in 2005. “But with each passing year, he seems more like a Lee Atwater political type than a former White House counsel,” he added, referring to the scorched-earth GOP operative.

As the White House’s top lawyer, he oversaw one of the ugliest confirmation fights ever — for Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas. He was a key backer of Neil M. Gorsuch to the Supreme Court in 2017.

Clayland Boyden Gray, the third of four brothers, was born in Winston-Salem, N.C., on Feb. 6, 1943. He dropped the first name, he later said, because he did not want to be called “Clay Gray.”

His paternal great-grandfather was chief executive of what became Wachovia Bank. His paternal grandfather was chief executive of R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. His father was president of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and oversaw the family’s newspaper holdings, including two dailies in Winston-Salem, and broadcast outlets in Georgia.

A conservative southern Democrat, Mr. Gray’s father also spent decades in Washington advising the Truman to Ford administrations on national security, defense and foreign intelligence matters.

The younger Mr. Gray described a largely solitary upbringing, a loneliness he attributed to his father’s frequent absence and his mother’s death when he was 10. He was sent away to St. Mark’s, a boarding school in Southborough, Mass., where he said he was “odd man out” as one of the few Southerners on campus.

At Harvard University, despite membership in elite societies and work on the college newspaper, he said he continued as a conservative Southerner to feel ill at ease. He mostly focused on his schoolwork, graduating magna cum laude in 1964 with a bachelor’s degree in history.

Following a stint in the Marine Corps, he enrolled at the University of North Carolina law school and became editor in chief of the law review. He finished first in his class in 1968, and parlayed a clerkship for Warren into a fledgling career at the politically prestigious Washington law firm Wilmer, Cutler & Pickering.

Partner Lloyd N. Cutler became his mentor at the firm, which cultivated trade associations for cars, chemicals and pharmaceuticals among its blue-chip clientele. Mr. Gray became a specialist in antitrust litigation and regulatory law and advanced rapidly to partner.

His marriage to Carol Taylor ended in divorce. Survivors include his daughter, Eliza Gray of Brooklyn; two brothers; and two grandchildren.

Mr. Gray left Wilmer, Cutler & Pickering (now WilmerHale) in 2005, after 25 years with the firm, and founded Boyden Gray & Associates, a firm that represents energy companies and other clients with interests in securities regulation.

A longtime advocate for alternate fuels, Mr. Gray once drove a methanol-powered Chevrolet to make his point. He was also passionate about tennis and was a regular partner of the late Katharine Graham, former chairman of The Washington Post Co.

Although many considered Gray one of the president’s most important advisers, he once said he only had a role in policy when complex legal issues were involved.

“This can be so technical, so esoteric, I’m called in as the translator,” he said.