In its first three months in charge, Newt Gingrich’s House Republican majority had approved all 10 planks of the “Contract with America,” including a balanced-budget law, the presidential line-item veto, an overhaul of welfare laws and a huge tax-cut proposal.

John A. Boehner’s House GOP majority in its first three months forced President Barack Obama to the bargaining table and eventually to accept a nearly $40 billion cut in spending by federal agencies.

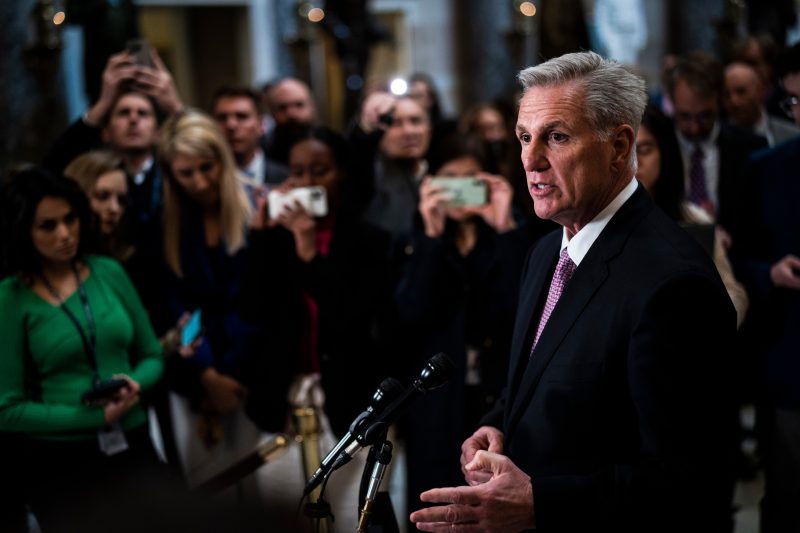

On Thursday, as they gathered to celebrate their first quarter in charge, Kevin McCarthy’s House Republicans had passed just two of their top 10 legislative priority items, and neither is expected to become law. Their biggest victories that will make it into law were blocking the implementation of a crime bill for the District of Columbia and forcing President Biden to end the pandemic emergency declaration a few weeks ahead of his original plan.

For Republicans across the country, this is not the revolutionary charge that Gingrich (R-Ga.) led in early 1995, trying to revamp almost every aspect of federal laws. Nor is it the fiscal police squad that Boehner (R-Ohio) led to two budget deals in 2011 that reined in federal spending for the next decade.

The new House Republican majority is taking a slow-and-steady approach to its confrontations with Biden and Senate Democrats, though often unsteadily because of the conference’s unruly factions. McCarthy (R-Calif.), who considers himself a Gingrich acolyte, does not possess the intellectual charisma that the former history professor used to keep the GOP caucus fairly unified in his first term.

More important, McCarthy lacks anything close to the 242-seat majority that Boehner had in his first term. That allowed Boehner to lose up to two-dozen votes from his side of the aisle and still muscle party-line legislation across the finish line. And although the new majority is investigating the Biden administration, similar to the GOP’s oversight in 1995 and 2011, today’s Republicans have repeatedly been distracted by demands from ex-president Donald Trump to re-litigate past grievances, losing time and energy they need for their agenda and planned investigations.

McCarthy’s House Republicans spent their first three months in charge assembling their leadership team and committee ranks. The nearly five-day squabble over choosing McCarthy as speaker forced concessions that placed more hard-line conservatives on important committees, which created an early emphasis on getting ideological unity on key proposals long before those plans head to the full House floor.

Items that were once considered slam dunks — such as a strong border security bill, a key issue for winning the majority in the 2022 midterms — are still marinating in the House Homeland Security and Judiciary committees.

House Republicans have hit the pause button on the early-January agreement that set approving a budget resolution that brings deficits into balance as the first critical goal for their agenda. At the pep rally Thursday, McCarthy rebuffed a reporter’s question about the delayed release of the GOP budget and the looming battle over raising the Treasury Department’s borrowing authority at some point this summer.

“First of all, if we’re talking about the debt limit, if we’re talking about the budget, that’s two different things,” McCarthy said. “Just so everybody knows, a budget resolution doesn’t go over to the president, a budget resolution doesn’t raise the debt limit.”

It is now possible that when House Republicans return from the two-week Easter recess, they will first deal with proposals to raise the debt limit, trying to win conservative concessions in exchange, before they formally take up the 10-year budget proposal that would then allow them to begin processing the annual federal agency appropriations.

What is called the X date, the absolute deadline at which the United States would default on its debt, remains unknown until tax season wraps up this spring and Treasury Secretary Janet L. Yellen can assess the balance, leading to a decision that will set in motion the first real struggle with Biden and a strict deadline for action.

Senior Republicans have sent dire warnings over the past days that, with no legislative action moving and no Biden-McCarthy talks on the horizon, Congress could sleep walk into a potential default.

“I don’t see how we get there,” Rep. Patrick T. McHenry (R-N.C.), the chairman of the Financial Services Committee and a close McCarthy ally, said at a Punchbowl News forum Tuesday. “And this is a marked change from where I’ve been.”

On Thursday, McCarthy said his lieutenants were assembling a package of spending cuts and other demands in legislation that also would raise Treasury’s borrowing cap. “If the president doesn’t act, we will,” he said.

Passing such a proposal will run into the same snags that have hindered the early efforts at rounding up support for border legislation, the budget resolution and other key items: With just 222 House Republicans, leadership can afford to lose only five votes.

And with several dozen hard-right conservatives demanding aggressive spending cuts, and given that several dozen Republicans are in competitive districts where moderation reigns, that is a tightrope act that this young majority has yet to truly walk on a big issue.

It is a stark contrast to Gingrich’s early days in charge.

Having become the first Republican speaker in 40 years, Gingrich fashioned himself as something akin to a prime minister. He was the first speaker to adopt the “first 100 days” standard that Franklin D. Roosevelt set for his presidency in 1933.

Just before his 100th day in power, he gave a nationally televised address in prime time that had the trappings of a State of the Union speech. “New ideas, new ways and old-fashioned common sense can improve government,” he said.

Much of Gingrich’s agenda crashed ashore in a Senate where liberal Republicans and conservative Democrats still existed, making centrism, not revolution, the coin of the realm. And all of his ego and confidence led him into a politically disastrous shutdown of the federal government, helping President Bill Clinton win a second term in 1996 and ending with Gingrich ousted as speaker and resigning soon after the 1998 elections.

Boehner had served as a junior member of Gingrich’s leadership team, so he saw Gingrich’s weaknesses and strengths up close, trying to learn from that in early 2011 after the Republican romp of 2010 left the conference with its largest majority since 1948.

Boehner decided to dig in for an immediate clash on that fiscal year — unlike today’s GOP leaders, who in December allowed the passage of a huge funding bill that clears the shutdown-deadline decks until Sept. 30. In mid-February 2011, Boehner held a week of late-night debate and amendment votes for a funding bill that eliminated dozens of federal programs and slashed some agency budgets by 40 percent.

“Democracy in action,” Boehner told reporters before 235 Republicans voted in favor.

By early April he had cut a deal with Obama that slashed that year’s agency funding, and by August he had won $1 trillion of spending cuts and a decade-long cap on agency budgets that liberals decried.

Yet, conservatives dismissed that victory as insufficient, and Boehner lost control of the GOP conference. Another long shutdown ensued in 2013, setting in motion the House Republican dynamics that exist today: If anywhere from a dozen to three dozen conservatives become sufficiently agitated, the House basically freezes in place.

Some of the 20 people who forced McCarthy’s pleadings and concessions in January were involved in helping eject Boehner as speaker in October 2015.

And, just as Boehner had a front-row seat to Gingrich’s performance, McCarthy served as a deputy to both Boehner and the next speaker, Rep. Paul D. Ryan (R-Wis.).

Rather than pushing for big early wins, McCarthy and his leadership team have opted for listening sessions with rank-and-file Republicans that are doubling as tutorials for a conference with little experience in big negotiations.

They forced Biden to retreat on his staff’s initial support for the D.C. crime law, which Republicans and some Democrats considered too soft on certain crimes, and then again on the resolution ending pandemic emergency provisions.

McCarthy grew up about 100 miles north of Hollywood, developing an affection for celebrity and an appreciation for theatrics that could fit into a Jerry Bruckheimer film.

He held elaborate rallies with dozens of Republicans in front of flags, celebrating the niche success on D.C. crime and the House’s passing its top legislative priority to increase domestic energy production, more than 85 days into the majority.

Those occasions gave the chance for staunch conservatives such as Reps. Andrew S. Clyde (R-Ga.) and Matthew M. Rosendale (R-Mont.), both of whom withheld support from McCarthy in early January, to share the stage with swing-district moderates including Reps. Michael Lawler (R-N.Y.) and David G. Valadao (R-Calif.).

These feel-good moments lack the concrete successes that lay behind the other Republican majorities’ celebrations, but McCarthy hopes that keeping everyone cheerful in the short run is worth more in the long run than those early wins that Gingrich and Boehner notched.