In February for Black History Month, USA TODAY Sports is publishing the series “28 Black Stories in 28 Days.” We examine the issues, challenges and opportunities Black athletes and sports officials continue to face after the nation’s reckoning on race following the murder of George Floyd in 2020. This is the third installment of the series.

Doug Williams’ deep throws were legendary. He could throw the ball 70 yards, or he could go intermediate and short, wherever his coach needed them.

“But he’s got more than just talent,” Eddie Robinson, his football coach at Grambling State University, said in November 1977. “He’s a natural leader, he’s intelligent, he’s a real student of the game.”

Robinson, who would go on to win more than 400 games, had already sent 160 players to pro football in more than three decades as a coach. Coaching Williams, his quarterback, Robinson said, was one of the thrills of his career.

Robinson was speaking ahead of the announcement of that year’s Heisman Trophy winner.

Super Bowl Central: Super Bowl 57 odds, Eagles-Chiefs matchups, stats and more

“We like to think we can dream the American dream,” Robinson said.

Though Williams had broken passing records at the HBCU, Robinson knew his chances of winning college football’s most prestigious award were minuscule. (He would finish fourth in the voting.) His chances of succeeding as a Black quarterback in the NFL seemed even smaller.

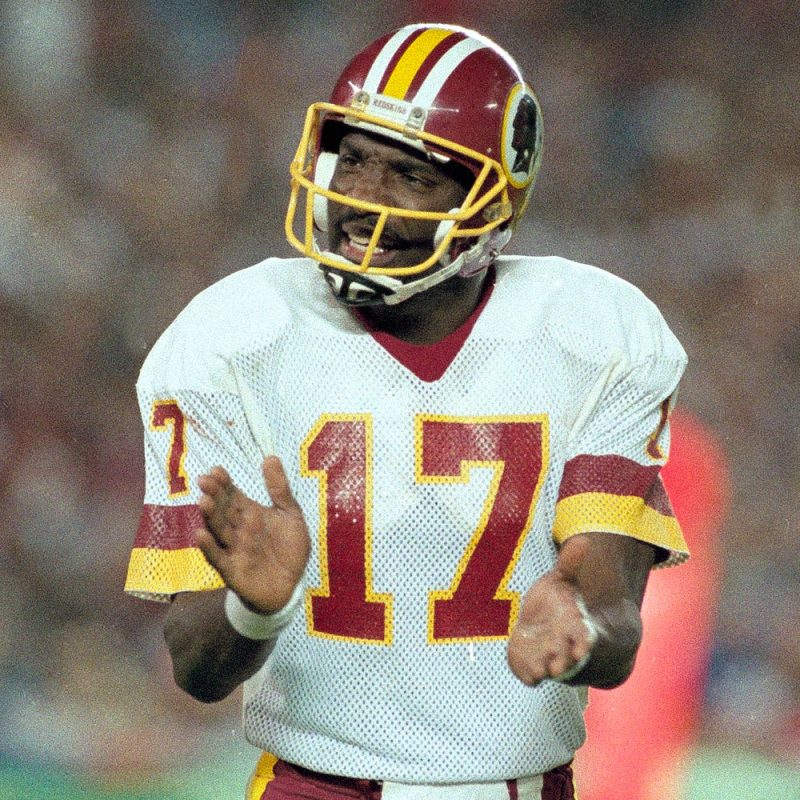

And yet, 35 years ago, Williams became the first Black quarterback to start a Super Bowl, then conquered the Denver Broncos with an MVP performance. In the buildup to Super Bowl 57, which pits two Black starting quarterbacks (Jalen Hurts and Patrick Mahomes) against each other for the first time, that part of Williams’ story has been recounted over and over.

To many, Williams’ story is one of the American dream. The narrative of Williams’ entire NFL career, however, is more one of America’s shortcomings.

It is a story of a Black man entering a near-impossible situation with no modern precedent for success. It is one of that man achieving near-instant prominence and empowering a team and a region of the South that wasn’t entirely prepared for him to do so. And, though it ended in triumph, it is a story of failure, perhaps on all sides, to fully understand one another.

‘Twice as tough’

“Williams has received a lot more publicity than his predecessors,” wrote Ulish Carter, a sports columnist for the Pittsburgh Courier ahead of the 1978 draft, “so whatever team selects him must be very careful in their treatment of him. … Once he is selected, the Black citizens in that city should start an all out drive to make sure he isn’t pressured out of the league or placed on the bench. If he doesn’t make it, it should be strictly because of his ability, not because the majority of the people aren’t ready or don’t want a Black quarterback.”

Carter was referring to James Harris and Joe Gilliam, two other Grambling quarterbacks who had been drafted by NFL over the previous 10 years but given minimal chances to succeed. Harris was picked in the eighth round by the Buffalo Bills in 1969, Gilliam in the 11th by Pittsburgh Steelers in 1972. Other Black college quarterbacks were simply drafted at other positions and not allowed to play quarterback.

Williams went 17th overall to the Tampa Bay Buccaneers in 1978.

“When I came into camp and they wanted to time me in the 40,” he would recall in 1988, “I told them I was going to play quarterback, not running back. I told them, ‘Quarterbacks don’t run.’ ‘

Robinson predicted Williams would turn the Bucs into winners in two or three seasons. Harris, who was Williams’ mentor, said he should prepare for the worst.

“I told him to go in there figuring he wouldn’t be treated fairly, that it would be twice as tough for him as for a white quarterback,” he told The Washington Post.

To that point, Harris had been the only Black quarterback to remain an NFL starter for an extended period. Despite a 21-6 record with the Los Angeles Rams between 1974 and 1976, he was booed by fans and relieved of his job.

The same year Williams was drafted, Warren Moon, who had quarterbacked Washington to a Rose Bowl victory over Michigan, decided to sign with the Edmonton Eskimos of the Canadian Football League instead of test the NFL draft. Despite being a standout high school quarterback at Hamilton High in Los Angeles, Moon went to junior college to prove he was a quarterback and, when he finally started at Washington, had to listen to fans shower him with insults related to his race.

John McKay, Williams’ coach in Tampa Bay, had ignored the bigoted protests when he was a coach at Southern California. McKay had been an assistant in the late 1950s when Willie Wood (the future Hall of Fame defensive back) was the school’s first Black quarterback. Similarly, as head coach, he had played quarterback Jimmy Jones for three years and recruited Vince Evans.

McKay, who won four national titles at USC, had managed two wins in the Bucs’ first two seasons of existence. When he installed Williams as his quarterback, the team won four of their first eight games before Williams broke his jaw. The team finished 5-11, winning once without Williams.

Feeling the pressure

By his fourth year in Tampa Bay, McKay had a defense, led by star defensive lineman Lee Roy Selmon, and he had a running back for USC, Ricky Bell, who could burst through holes. He also had Williams, to whom the coach became a father figure. Writers made comparisons to Branch Rickey and Jackie Robinson.

The head coach was 56 and had an affinity for cigars and floppy hats. Williams was his star pupil: 6-4 and 215 pounds with a quick release and a disarming smile. Most important, he had his coach’s full support.

The 1979 Bucs jumped out to a 5-0 start. Win No. 5 pitted Williams against Evans, who started for the Bears. As Williams hurtled the Bucs toward the playoffs, the Bucs, like the Dodgers three decades before, became Black America’s team. Tampa Bay loved Williams, it seemed, as long as his interceptions (eight in a three-game stretch) didn’t cost the team games. When Evans got sidetracked after Williams beat him, Williams began to fully feel the pressure of being the NFL’s only Black starting quarterback.

As dispatches about the Iran hostage crisis drifted home, one Tampa Bay-area columnist quipped that Williams could “overthrow the Ayatollah.” After a game when the fans at Tampa Stadium had booed him, he snapped.

“A lot of people don’t look at my performance and judge me,” he said, according to The Baltimore Sun. “They look at my color and judge me. A lot of people can’t accept that I’m a Black quarterback and starting in the NFL. But it doesn’t bother me. I’m going to the bank tomorrow.”

Williams apologized for lashing out. McKay stuck with him and Williams led the Bucs to a home NFC championship game with the Rams. But his coach couldn’t fully shield him from the intense pressure he felt by season’s end.

“I think Doug was the first Black quarterback to make it big in the NFL because he was the first one that was good enough,” McKay said, according to The Washington Post, in the leadup to the game. “Hell, Willie Wood couldn’t throw the ball end over end. Anyway, I hope that’s the reason. Anything else would reflect very badly on our society.”

‘I went for the money’

The hard-hitting Rams left the Bucs maimed. Williams completed 2 of 13 passes for 12 yards and sustained another vicious hit that left him with his right arm in a sling. McKay pointed to receivers who were unimaginative with their routes and poor blocking but not Williams. The coach exploded the next season when a Texas reporter quoted Williams’ Southern drawl verbatim in a story. The Afro American newspaper pointed out that while similar critics once found Dizzy Dean’s malaprops colorful, Williams’ grammar made him dumb.

“He doesn’t go anywhere where he’s treated like a football player,” McKay said. “Doug Williams is a young quarterback. He’s not a Black quarterback. No more than David Lewis is a Black linebacker. Or O.J. Simpson was a Black running back. It’s time people grow up.”

When reporters pointed to his performance at Dallas in which Williams had two interceptions, the coach said: “And he had five passes dropped. So that gives sportswriters a chance to say what a poor quarterback and passer he is. It’ll just give another racist a chance to say that Doug is not good, and I’m getting sick of it.”

When Williams approached his locker, he knew he might find hateful letters from fans or something worse. Williams, though, commanded the respect of his teammates, half of whom were Black.

By 1982, when he had led the Bucs three playoff appearances in four years, he was still one of the lowest paid quarterbacks in the NFL at $125,000 per year. The Bucs had always thought he would be their quarterback of the present and future, and began to negotiate a long-term deal with him. Williams wanted $600,000. Don’t worry, owner Hugh Culverhouse told his coaches, Williams will sign. Williams didn’t.

In fact, he sat out the 1983 season when Tampa Bay wouldn’t budge. Williams went home to his hometown of Zachary, Louisiana. “I hope the Bucs go 0-16 but all my friends make the Pro Bowl,” he said that fall.

The comment hurt McKay, but Williams was hurting much worse. It wasn’t just the turmoil of the contract dispute weighing on him. That year, his wife Janice had died suddenly of brain cancer. They had a 7-week-old daughter, Ashley. It was the darkest period of Williams’ life. He said he could have turned to drugs or alcohol or just given up if he hadn’t had to care for Ashley.

When the Oklahoma Outlaws of the United States Football League, a rival to the NFL, met his asking price in a multiyear deal, Williams took it.

“He simply wanted out,” Bill Tatham Jr., the Outlaws’ CEO said, according to The New York Times. “It only took about an hour to work out a deal.”

“I went for the money,” Williams would tell the New York Amsterdam News in 1986, but said he wished things worked out differently. He would return to the Bucs to work in their front office from 2004 to 2010.

“Things were getting sticky down there even before the contract thing came up,” he said. “There was a lot of tension. Some of the fans began getting on me. You know, people get on the quarterback everywhere when they think you should be winning more. But there were a lot of racial things yelled out. I really heard them on the sidelines. There was this one guy who seemed to pay his money just to remind me what color I was.”

When he left, Bucs attendance plummeted, much because the team went 10-34 over the next three seasons, but also because a lot of fans missed Williams.

‘We want Doug’

Joe Gibbs had been an assistant coach for McKay in 1978. In fact, he had flown to Tampa ahead of the draft and gotten to know Williams. McKay drafted Williams on Gibbs’ advice.

Gibbs hadn’t seen Williams play in years. The USFL experiment had lasted two seasons, during which Williams had had surgery on both knees.

Gibbs acted on a hunch and called Williams, now 31, offering him a shot at being Jay Schroeder’s backup in 1986. Tampa Bay traded his rights to Washington for a fifth-round draft pick.

Williams looked sharp in practice, stilling showing that zip on his passes. There was one obstacle he had to clear. Gibbs knew he needed work to see what he could do in a game situation. He termed it a “real bad situation” but didn’t see any way out of not playing Williams in relief of Schroeder in a preseason game in Tampa.

Williams had played there on the road in the USFL. When he arrived the third time before more than 45,000 fans, there was a mix of boos and cheers.

“I put my helmet on my head and tried not to hear any of it,” he said.

One local writer heard fans chant “We want Doug.” Another observed how 100 fans mobbed him outside the locker room and wrote, “It was like a rock star had come to town.”

That was nothing compared to the scene he faced ahead of Super Bowl 22, when reporters asked him about seemingly every angle about his achievement given the color of his skin. They were questions, in fact, he was already tired of answering from his days in Tampa Bay.

“If I play in this league for 20 years, I’m still going to be a Black quarterback,” he had told The Washington Post in 1980. ‘I know that. Every morning when I wake up and look in the mirror, I know I’m a Black quarterback.”