The 2019 state budget negotiations in Minnesota were tense, with a deadline looming, when the speaker of the House offered Gov. Tim Walz a suggestion for breaking the impasse.

They both knew that the Republicans’ top priority was to create a school voucher-type program that would direct tax dollars to help families pay for private schools. House Speaker Melissa Hortman, a Democrat, floated an idea: What if they offered the Republicans a paired-down version of the voucher plan, some sort of “fig leaf,” that could help them claim a symbolic victory in trade for big wins on the Democratic side? In the past, on other issues, Walz had been open to that kind of compromise, Hortman said.

This time, it was a “hard no.”

“It was like kind of ‘Over my dead body,’” she recalled in an interview. “He would have shut down state government if they insisted on vouchers.”

Since taking office as governor in 2019, Walz, the Democratic nominee for vice president, has earned a national reputation as a progressive willing to champion and experiment with liberal ideas for governing. That approach was especially apparent in his handling of Minnesota’s public schools, according to critics and allies, who said Walz has retained the heart and priorities of the teacher he was for nearly two decades before seeking elected office.

He used his position’s formidable sway over education to push for more funding for schools and backed positions taken by Education Minnesota, the state’s teachers union of which he was once a member. His record on education will probably excite Democrats but provide grist for Republicans who have in recent years gained political ground with complaints about how liberals have managed schools.

Teachers and their unions consistently supported Walz’s Minnesota campaigns with donations, records show. And in the first 24 hours after he was selected as Vice President Kamala Harris’s running mate, teachers were the most common profession in the flood of donations to the Democratic ticket, according to the campaign.

During the chaotic 2020-21 pandemic-rattled school year, Walz took a cautious approach toward school reopening that was largely in line with teachers, who were resisting a return to in-person learning, fearful of contracting covid. Critics say that as a result, Minnesota schools stayed closed far too long — longer than the typical state — inflicting lasting academic and social emotional damage on students.

Asked about the covid response, Harris-Walz campaign spokesman Kevin Munoz shifted the blame to Donald Trump, who was president at the time: “Schools were closed because Trump failed on Covid.”

He added that Harris and Walz would be far better for American education than their opponents.

“They will fight for a strong public education system, schools safe from gun violence and investing in every community,” he said. “It’s a stark contrast to Trump and (JD) Vance.”

Walz also advanced his own robust and liberal education agenda. He fought to increase K-12 education spending in 2019, when he won increases in negotiations with Republicans, and more dramatically in 2023, when he worked with the Democratic majority in the state House and Senate. He won funding to provide free meals to all schoolchildren, regardless of income, and free college tuition for students — including undocumented immigrants — whose families earn less than $80,000 per year. He also called out racial gaps in achievement and discipline in schools and tried to address them.

And as culture war debates raged across the country in recent years, Walz pushed Minnesota to adopt policies in support of LGBTQ+ rights.

“He understands what our schools and students need,” said Jake Schwitzer, executive director of North Star Policy Action, a liberal research and advocacy group that is funded in large part by labor unions. “He believes in the power of government to improve people’s lives and in his responsibility to move our policies in that direction.”

Walz’s sweeping agenda has been met with pushback from conservatives, who point to falling test scores to argue that he was focused on the wrong issues and catering to the teachers union.

Scores fell across the country during the pandemic, but in Minnesota, reading and, in particular, math scores fell more than the national average. In 2015 and 2017, the state’s fourth-grade math scores were 10 points higher than the average national score on the National Assessment of Educational Progress; in 2022, they were only four points higher. Eighth-grade math scores also fell faster than average, to their lowest level in three decades.

Cristine Trooien, a mother of three and executive director of education advocacy group the Minnesota Parents Alliance, which formed in 2022 to fight for parents’ rights in education, argued that public schooling in her state “has literally never been worse.”

“Sadly for Minnesota students, the union-controlled Walz administration decided it would rather use its power, influence and bottomless resources to saturate the K-12 conversation with straw man issues like ‘book banning,’” she said in an email, “than confront and solve the literacy and student achievement crisis.”

Delivering for teachers

When Walz first ran for governor in 2018, he filled out a 13-page questionnaire from Education Minnesota and left no doubt about his position opposing vouchers.

“As a former public school teacher, I will always do everything in my power to protect our public education system from privatization,” he wrote.

His promise was quickly put to the test.

During budget negotiations in 2019, Republicans were pushing for a variety of tax cuts, but their top priority was a tax credit for donations to a scholarship program — a type of voucher program used in many other states. They argued it would give students stuck in poorly performing schools more options. Teachers and most Democrats opposed it, saying vouchers drain money from public schools and improperly mix tax dollars with religious private school instruction.

As the budget deadline approached, Republican Paul Gazelka, the Senate majority leader at the time and one of Walz’s staunchest political opponents, continued to press his voucher plan but met unyielding resistance.

Hortman recalled that at a point during their closed-door talks, the governor replied, “You know I’m a member of Education Minnesota, right?” (He actually was no longer a member but had been as a teacher.)

Gazelka walked away frustrated.

“I was willing to give up a lot to get that, but it just didn’t happen,” Gazelka said. “We just weren’t asking that much, but that’s how passionate he was against any kind of education reform. He would never go against the teachers union.”

Four years later, Walz pressed his own education agenda.

In the 2022 elections, Walz was reelected, and Minnesota Democrats took control of the Senate. Democrats now had a “trifecta” — governor, House and Senate — and a $17.6 billion budget surplus.

After taking his oath of office in January 2023, Walz said Minnesota had a historic opportunity to become the best state in the nation for children and families. His proposals included a huge increase in K-12 education spending.

“Now is the time to be bold,” he said.

The final budget agreement in 2023 increased education spending by nearly $2.3 billion, including a significant boost to the per-pupil funding formula that would be tied to inflation, ensuring growth in the coming years. Total formula funding for schools would climb from about $9.9 billion in 2023 to $11.4 billion in 2025, according to North Star Policy Action. The budget also included targeted money for special education, pre-K programs, mental health and community schools.

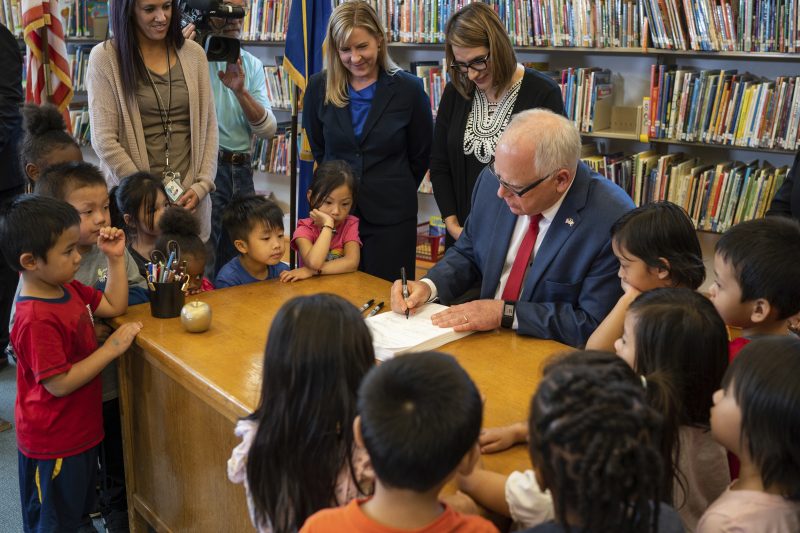

Walz also signed legislation providing free school meals for all students — a signature achievement — not just those in low-income families who are eligible under the federal program.

“Our union came to him with a pretty big list,” said Denise Specht, president of Education Minnesota. “He certainly delivered.”

A covid shutdown

Like every state, Minnesota shut down its schools in March 2020 in response to the coronavirus. As the pandemic persisted, resistance to the state’s response grew.

For the 2020-21 school year, the governor left decisions on reopening partly up to school districts. But he also mandated that, in order for schools to reopen fully, localities had to see their virus cases fall below 10 per 10,000 people over a two-week period. That meant that some school districts — including big ones in Minneapolis and St. Paul — would stay remote, or mostly remote, for months.

He loosened these restrictions near the end of 2020, allowing elementary schools to reopen in January 2021 regardless of case counts. The month afterward, he permitted all middle and high schools to open back up, too, and declared every campus must offer some in-person teaching by March 8.

By March 2021 — a full year after the initial shutdowns — 90 percent of Minnesota districts and charter schools were offering at least partial in-person instruction, according to Walz’s office.

Minnesota schools remained remote longer than average among states, said Nat Malkus, a researcher at the American Enterprise Institute who has analyzed the length of time districts remained remote during the 2020-21 school year. In Malkus’s ranking of states — from most remote learning to most in person — Minnesota came in 19th out of 50 states, based on the number of weeks of full or partly remote school, weighted by student enrollment.

The state’s ranking is “not too bad,” Malkus said. “That makes it somewhat worse than average, but better than average for blue states.”

Critics, both then and since, said Walz made it too difficult for schools to reopen, inflicting irreparable damage on children’s academics and mental health.

In fall 2020, a mother of five, distressed by school closures and a pause of youth sports statewide, founded an advocacy group called Let Them Play Minnesota. The group soon swelled to 25,000 members and sued Walz twice over the sports halt, although both suits were later dismissed. The mother, Dawn Gillman, a Republican, rode the following she gained for her advocacy to a seat in the Minnesota House.

A few months later, Republicans in the Minnesota Senate rebuked Walz for school closures by proposing a bill that would have stripped the governor of the emergency powers he used to close campuses. The measure passed the Republican-dominated chamber but died in the Democratic-controlled House.

Some schools also tried to resist.

Sibley East Public Schools, a rural district southwest of the Twin Cities, voted in September 2020 to ignore the state’s reopening restrictions and shift to in-person instruction for all students — only to back down a week later and resume hybrid schooling. The district fell in line after the state schools superintendent called the Sibley East superintendent, the Star Tribune reported, and the district’s attorney warned of a possible legal battle with the state.

How things played out in Sibley East was typical of the governor’s pandemic policies, said Scott Jensen, a Republican and former Minnesota state senator who lost to Walz in the 2022 gubernatorial race.

“Tim Walz gave the public impression he was letting individual school districts make the decision they needed to make, but I don’t think that was quite genuine,” Jensen said. “I think school districts felt a tremendous amount of pressure to toe the line.”

But Walz enjoyed the strong and continued support of teachers’ unions for most of his pandemic decisions.

He pursued teacher-friendly policies, issuing an executive order that “strongly” discouraged schools from asking educators to provide in-person and virtual instruction simultaneously, a form of teaching that many found burdensome. The order also mandated that districts give teachers an extra 30 minutes of planning time a day. And like a handful of other states, he put educators near the top of the priority list for covid vaccinations once they became available, holding mass vaccination events for them. As a result, 55 percent of school staff and child-care workers were vaccinated by March 2021. His administration also delivered biweekly, free shipments of coronavirus tests to schools statewide.

“There was really no playbook, nobody knew what to do,” said Specht, the Education Minnesota president. Walz “looked to the science, and he engaged our union quite a bit.”

Pushing against ‘hatred and bigotry’

In his 2023 State of the State address, Walz drew a pointed contrast between the culture wars raging in states such as Florida and the situation in Minnesota.

“The forces of hatred and bigotry are on the march in states across this country and around the world,” Walz said. “But let me say this now and be very clear about this: That march stops at Minnesota’s borders.”

Through his tenure, he repeatedly took up the causes of LGBTQ+ rights and racial justice.

He signed a measure prohibiting public and school libraries from banning books due to their messages or opinions, and another granting legal protection to children who travel to Minnesota for gender-affirming care.

“He’s a strong supporter of kids, he wants to build schools where young people can thrive,” said Rep. Leigh Finke (D), Minnesota’s first openly transgender lawmaker. “In Minnesota, we are providing meals. We’re not taking away books.”

Walz also signed a law last year that requires menstrual products be made available in all school bathrooms regularly used by “menstruating students” in grades 4 through 12, permitting the placement of pads and tampons in boys’ bathrooms. The inclusive language, meant to accommodate transgender children, has since drawn attacks from Republicans; conservatives in the state tried to amend the law so it only applied to women-only and gender-neutral restrooms, but failed.

Walz’s administration also updated teacher certification standards to require, among other things, that candidates examine their biases and affirm students’ gender identities and sexual orientations. And his education department revised state social studies standards to require ethnic studies, including an examination of social identities of race, gender, religion, geography and ethnicity.

Walz’s agenda drew backlash from Republican lawmakers in the state, who decried the book removal law as unnecessary — and warned that permitting gender-affirming care would undermine parental rights. Conservatives also unsuccessfully challenged the standards for teacher certification and social studies in court. In their own platform and a spate of 2022 bills, Republicans sought to boost parents’ control of education, for example proposing parents should review curriculums.

Walz has also attempted to address the significant racial disparities in academic achievement. White students score higher on standardized tests, according to a 2019 study by the Federal Reserve of Minneapolis, and Minnesota’s racial gap in graduation rates that year was the largest in the country, per the state’s Department of Human Rights.

Among the governor’s ideas to fix the problem: anti-bias training for school staff, stepped-up recruitment of teachers of color and more a inclusive curriculum.

Still, after five years of Walz’s governance, “we haven’t been able to move the needle much,” said Josh Crosson, the executive director of EdAllies, a statewide education group that advocates for students of color, those with disabilities and low-income learners. He said that’s partly due to the pandemic.

Crosson pointed to two Walz administration initiatives he thinks will help down the road. The 2023 READ Act requires schools to adopt “evidence-based” reading curriculums and teaching practices, such as sound-it-out instruction known as phonics. The act also gave schools $70 million to train teachers, conduct literacy assessments and purchase new curricular materials.

Crosson also cited a law Walz signed, which took effect last school year, forbidding suspensions as a form of punishment for students in kindergarten through third grade. (A 2022 state report found that Black students were eight times more likely to be suspended or expelled than White students.)

“It is a long-term investment in closing gaps in the future,” Crosson said of the two initiatives.

Nonetheless, Crosson said he wished Walz had done more to prevent school police officers from using a hold known as “prone restraint” on children in school. Black, multiracial and Native American special education students are disproportionately likely to be placed in physical holds at school, according to data from the Minnesota Department of Education.

After the murder of George Floyd, the governor signed a law forbidding prone restraints, which spurred many police departments to pull their officers from schools in protest. Ultimately, the Minnesota legislature reversed itself and passed another law allowing such restraints in “physically dangerous” situations, which Walz signed. And, Crosson said, he would have liked to see Walz do more to diversify Minnesota’s teacher workforce, which remains overwhelmingly White.

Mani Sayes, a biracial mother living in Minnesota’s Lakeville school district, said she is generally pleased with how Walz has conducted himself when it comes to education. She praised his attention to educators’ needs and his focus on achieving racial equity.

“He ensures when kids can go to school, they can learn,” said Sayes, 40. “If that means putting in free lunches to take the burden off parents, then he does that.”