Imagine growing up in a city where three future Hall of Fame center fielders play.

Imagine walking out of your apartment and to the street corner, where you argue with your friends over a soda or an ice cream about which one of those three is the best.

Imagine going a few more blocks and seeing all three center fielders, and everyone they played against, right in front of you, in the epicenter of the national pastime.

Terry Cashman, who lived these experiences as boy, once put them into a song about New York baseball in the 1950s.

We’re talkin’ baseball!

Kluszewski, Campanella.

Talkin’ baseball!

The Man and Bobby Feller.

The Scooter, the Barber, and the Newc,

They knew ’em all from Boston to Dubuque.

Especially Willie, Mickey, and the Duke.

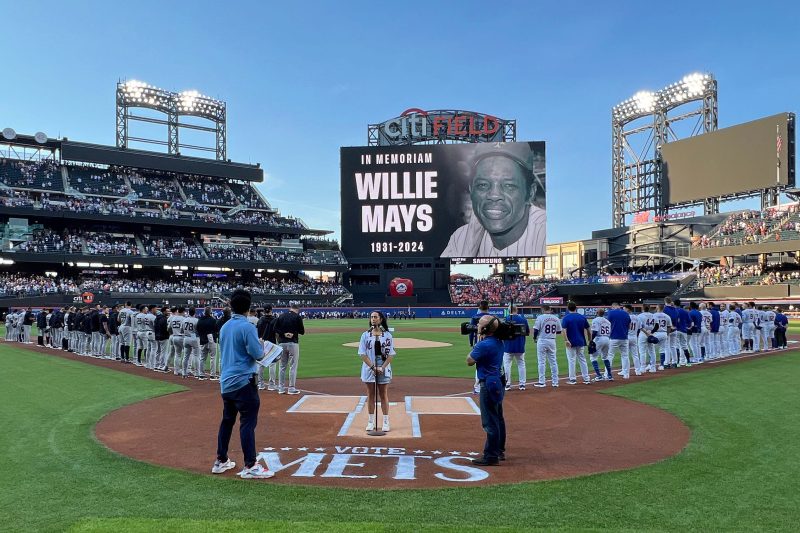

The title of Cashman’s 1981 creation, “Talkin’ Baseball,” became a part of the sport’s lexicon. Its words always come back to three men: Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle and the Duke Snider. The song’s message is especially poignant now, on Hall of Fame induction weekend, because they are all gone. This summer, we lost Willie Mays, who was 93 and the last living member of New York’s super center field trio.

Cashman got to know all three men in adulthood, and they lived up to his childhood imagination, especially one of them.

“There was nobody like him,” Cashman, now 83, says of Mays.

The singer was a former baseball player himself who didn’t quite make it as a pro. Yet Cashman’s story is one of maintaining your love for a sport, and your faith in your hero, even when you learn everything about both of them isn’t perfect.

He spoke with USA TODAY Sports about what it was like to know Mays, as well as Mickey and the Duke, and what today’s young athletes (and their parents) can learn from their memories.

(Questions and responses are edited for length and clarity.)

1. Share your love: Sports bring families together

Dennis Minogue, Cashman’s given name, was born into a family of New York Giants baseball fans. His brother Tommy, just back from World War II, took Dennis to his first game – a Bob Feller no-hitter at Yankee Stadium – when he wasn’t quite five years old. When Dennis got older, he was greeted after school by the sounds of afternoon Giants games drifting from his mother’s kitchen radio.

That team was mostly an afterthought in those day until a life-changing player arrived in 1951. Dennis’ two older brothers nudged him to watch Willie Mays. Mays seemed to be a step ahead of everyone else, anticipating where the ball would go and going after it hard over every inch of the Polo Grounds’ monstrous center field.

Dennis, who would change his name to Terry Cashman in the music business, couldn’t take his eyes off of him.

USA TODAY: Talk about how you became a Mays fan.

Terry Cashman: Bobby Thomson was my favorite player. Then one day in 1951, this guy shows up, his name is Willie Mays. And right away, just that name excited me, and I was 10 years old and started following him. And the first couple of weeks weren’t very good (Mays went hitless in his first three games). But he still was the Giants’ centerfielder and replaced Thomson, whom they moved to third base. Tommy took me to an afternoon game, and they were playing the Boston Braves. Willie got up against Warren Spahn and hit a ball that’s still going. He hit it over the roof in left field and that was his first hit. And I fell in love with him that day. And from then on, I just followed everything he did.

I rooted for him very hard when he had bad times. I would suffer myself and wait for him to get back on the ball, which he always did. He was so exciting, the way he ran the bases and the catches that he made in the outfield.

USA TODAY: He seemed like a good player for kids to look up because he hustled and he had a good attitude. Did you notice those things when you were a kid?

TC: I don’t think you really notice because he didn’t do anything wrong. He played the game the way you should play the game. What I found out later was his knowledge of the game and the way that he would position players defensively and would tell other players where [opponents] would hit the ball. But just the way he played and the way he hustled was unique.

I really felt that I knew him as a ballplayer. You’ve probably seen films of him playing stickball with the kids in Harlem, so that endeared him to everybody. He seemed like a really happy-go-lucky, nice guy.

2. Follow your passion: Love for a sport can push us forward long after we’re done playing

Before and after games in the 1950s, Mays played stickball and got ice cream with kids at 155th Street and St. Nicholas Place, where he lived, with the approval of Giants manager Leo Durocher.

“Leo used to give me the money to buy the ice cream, so we had no problem,” Mays told sportscaster Warner Wolf in 1981. “It kept me off the streets, so I enjoyed it very much.”

He flashed a gleaming smile. It was that hero’s look and feel that inspired another boy in Northern Manhattan to play baseball. That boy pitched in the Detroit Tigers organization in 1960 but it ultimately found another path that truly made him happy.

USA TODAY: You were a pretty good ballplayer yourself. Did you still love playing when you got to the minor leagues?

Terry Cashman: I was 18 when I got signed and I should have waited and played a couple more years in college. I really wasn’t ready for the minor leagues. I didn’t like playing for money. That’s all that anybody talked about was how much money you make. Of course I wanted to make money as a professional but I didn’t take it as seriously as some of the guys I was around.

There was a pitcher named Gary Waslewski who played in the major leagues. He was on a Pirates farm team that we played against. He was pitching against us and there was about as much chance of us winning that game as going to the moon. And the pitcher on our team came into the dugout and said something like, “I gotta get this guy out of the game.” And the next time Gary got up, he hit him in the head. And I said, “I couldn’t do that if that’s what you have to do to get ahead in this game.” Not everybody did that but it was a terrible thing. I thought I’d better stay in school and pursue music, which I loved as much as baseball.

3. Be yourself: Sports heroes are humans, not deities

Cashman was an English major in college who found music, hitting it big when he co-wrote the song, “Sunday Will never Be the Same.” He still daydreamed about baseball. He found himself one day years later staring into a picture of Mays, Mantle, Snider and Joe DiMaggio together.

He drifted off to sleep that night thinking about his childhood and woke up with a song in his head. He wrote it in 20 minutes. DiMaggio, who had been in his prime in the 1940s, didn’t fit into it. It was all about Willie, Mickey and the Duke.

Singing about them opened up a world he could never have imagined. Snider, then a broadcaster with the Montreal Expos, showed up at his front door and they went to dinner. Cashman was invited to meet Mantle at an event and was called to a hotel to do a press conference with Mays he would never forget.

USA TODAY: What was that like, getting to meet him after you admired him for all those years?

TC: It’s something that I treasure until this day. He was working at Bally’s. (Mantle also worked for a casino.) We had given Duke and Mickey checks for $2,500 each so this was an opportunity to bring the check for Willie. Rusty Staub was a very good friend of mine and he said, “Willie’s nickname is ‘Buck,’ and he’s probably gonna expect something from you for using him in a song.’ I went in the room with a number of people from the press and I sat down at a table. They’re playing the song over speakers. And in comes Willie. He sits down next to me and he says, “Do you have a release for this song?” And I said, “Willie, I just want you to know that I’ve loved you since I’m 10 years old and I would never do anything to hurt you.” And I reached in my pocket and I pulled out the check. He looked down, took the check and stood up and said, “You know, this song’s got a good beat.” (Laughs.)

He sat back down and said, “I want to take you to lunch.” At lunch, I said to Willie, “Everybody talks about the catch on Wertz in the ’54 World Series, but I think the greatest catch you ever made was on Bobby Morgan in ’52.” (Mays) made a catch in Ebbets Field where he dove on the warning track and caught the ball and knocked himself out by hitting his head on the wall. And he said, “You saw that catch?’ He laughed and he said, ‘You know more about me than I do.”

And every time I saw him after that, he was always very friendly to me.

4. Be nice: Your ultimate legacy is how you treat people, not how well you play

Tom House, a pitching and throwing coach for famous baseball and football players, loves to work with kids. He posted recently on social media about how much a compliment can help a young athlete’s confidence.

The words especially resonate when they come from a person of stature on the team. Al Downing, the Yankees’ first African American pitcher, recalls how he felt in his first full season (1963) after Mantle returned from a long injury stint and approached him in the clubhouse.

“Great job,” Mantle said. “Keep it up.”

“One of the biggest boosts I got,” Downing, who pitched in the big leagues for 14 more seasons, told me in 2022. “You don’t get that from the star of a team.”

When Mays started his career with the Giants by going 0-for-12, he found comfort in Durocher, his manager.

“I was crying,” Mays told Wolf, the New York sportscaster, during the interview in 1981, “and Leo came to me and he says, ‘Son, as long as I’m manager here, you’re my center fielder. Don’t worry about hitting. You just go out and field. We’ve got enough hitters for you.’ That carried me over.”

The Wolf interview brought Mays, Mantle and Snider together for the first time on the same television show. They came across as regular guys: Charming and grounded in the reality that stars weren’t paid enough in their day and had to work in retirement.

They realized what Cashman did for them, too.

USA TODAY: There’s something still so poetic about Willie, Mickey and Duke. Was there a certain way about the three of them that differentiated them from others?

TC: To have three Hall of fame center fielders in the same city at the same time, putting up record numbers, had never been done before, and it will never be done again. I wrote (the song) because it captured a certain time. We paid them royalties and we give them a share – those were advances – because I didn’t want anybody saying that we took advantage of these guys to make money. They all we’re very grateful.

The three of them were so good to me. I saw Duke at an autograph signing session. I would see Mickey all the time because he had had a restaurant in New York. He was always very nice to me. And like Willie, he would sign anything that I would ask him. I would like people to know that they were terrific people. And three of the three of the greatest players who ever lived.

Steve Borelli, aka Coach Steve, has been an editor and writer with USA TODAY since 1999. He spent 10 years coaching his two sons’ baseball and basketball teams. He and his wife, Colleen, are now sports parents for a high schooler and middle schooler. His column is posted weekly. For his past columns, click here.