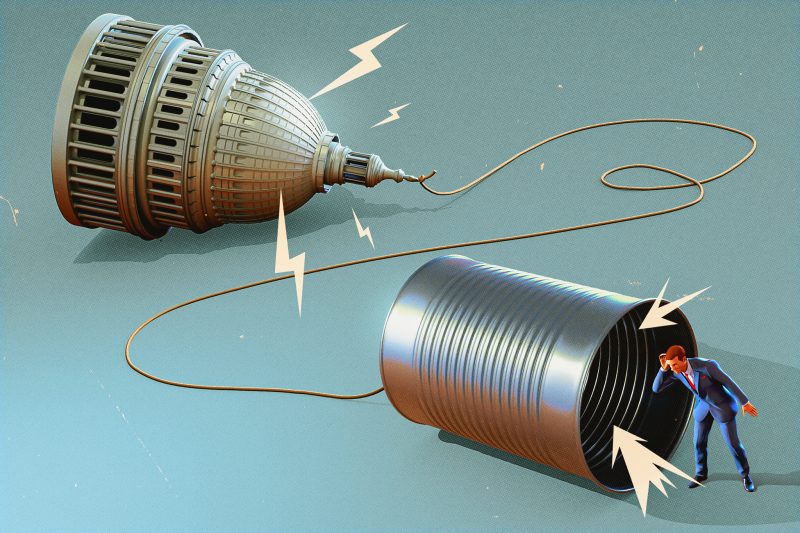

Members of Congress hear a lot of secrets: classified briefings, confidential previews of pending legislation and the private opinions of constituents, regulators, corporate executives and world leaders.

Watchdog groups have long believed that some lawmakers use that information to make money in the stock market. Now a loose alliance of traders, analysts and advocates is trying to let Americans mimic the trades elected officials make, offering tongue-in-cheek financial products — including one named for former House speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) and another that refers to Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Tex.) — that track purchases and sales after lawmakers disclose them.

Collectively, these investment vehicles have attracted hundreds of millions of dollars. At times, congressional investigators have used them to keep tabs on suspicious trading activity, according to people familiar with these investigations who spoke on the condition of anonymity because they are not authorized to speak to the media.

“Our mission isn’t to make everyone millionaires — it’s actually to highlight the hypocrisy of congressional trading in an effort to bring more transparency and trust back into our government,” said Christopher Josephs, the founder of Autopilot, an app that allows ordinary investors to mimic the trades of leading politicians, top hedge funders and other famous traders. “Hopefully it’s helping, but our slogan is, if you can’t beat them, join them.”

Members of Congress are permitted to trade on the markets, but a 2012 law, the Stock Act, clarified insider trading restrictions for lawmakers and ramped up reporting requirements. Lawmakers are banned from trading based on material and nonpublic information they learn through their jobs and have 45 days to disclose any trades they or their immediate family members make.

Because the trackers rely on lawmakers’ legally mandated (and delayed) disclosures, they don’t allow the average American to make identical, same-day trades.

Those delays likely cut into users’ returns. That’s not the point, tracker boosters say. Their goal is to shine a light on congressional stock trading.

But the rise of these platforms is an alarming sign of distrust constituents have for their elected representatives, said Delaney Marsco, the director of ethics at the Campaign Legal Center, a nonpartisan government watchdog group.

“A lot more people than we would like” believe lawmakers use information gained from their positions to “make significant gains to their stock portfolios,” Marsco said. “That’s incredibly damaging to the public’s trust.”

The push to allow ordinary investors to mimic lawmakers’ stock trading began in 2019, when an anonymous social media account called Unusual Whales began publishing reports analyzing politicians’ financial disclosures.

The account spotlighted trades it deemed suspicious, including some lawmakers’ decisions to sell large portions of their portfolios as the coronavirus spread across the globe.

Around the same time, James Kardatzke, an undergraduate at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, started scraping up congressional data. In 2020, he launched one of the first websites that tracked trades disclosed by Pelosi, whose venture capitalist husband, Paul, is a successful investor. (The former speaker has long maintained that she does not personally own any stock and has no knowledge of or involvement with her husband’s investments.)

Quiver Quantitative, the company Kardatzke co-founded that year with his twin brother, Chris, offers a data platform that highlights congressional trades and potential conflicts of interest, including lawmakers’ corporate donors, proposed legislation and net worth.

Josephs’s Autopilot originated as a social investment app called Iris that aimed to make it easier for ordinary investors to mimic their friends’ trades. But after copying famous investors’ trades proved more popular, the company pivoted.

According to Josephs, investors have so far routed some $130 million through Autopilot — $60 million of which has gone toward copying Pelosi, whose portfolio ranks as one of the app’s most popular, alongside Berkshire Hathaway’s Warren Buffett.

The Autopilot portfolio that mimics trades disclosed by Pelosi posted a 45 percent gain in 2023, above the S&P 500’s 24 percent gain that year.

Quiver and Autopilot allow ordinary investors to follow lawmakers’ trades and copy them if they choose. But last year, Christian Cooper, a derivatives trader and portfolio manager at Subversive Capital Advisor, partnered with Unusual Whales to launch products to make the process even simpler.

They launched two exchange-traded funds, or ETFs — investment funds that trade like stocks — that allow everyday investors to mimic lawmakers’ investment strategies. Unusual Whales Subversive Democratic ETF (NANC) and the Unusual Whales Subversive Republican ETF (KRUZ) — whose tickers nod to Pelosi and Cruz, a member who is not a prolific stock trader but has high name recognition — hit the market in February 2023.

NANC, which invests in stocks purchased by Democratic members of Congress, outperformed the overall U.S. stock market from its inception through April 30 of this year, according to an independent analysis by Elisabeth Kashner, director of global funds research and analytics at FactSet, a financial data and technology company. KRUZ, which invests in stocks purchased by Republican members, hasn’t done as well, underperforming the overall market. KRUZ ended April with $16 million of assets versus NANC’s $78 million. But Kashner argues that those outcomes should come with a caveat.

“While NANC’s run-up has been impressive, it’s statistically insignificant, meaning that there’s a decent chance that the outperformance to date has been random,” Kashner said. “Ditto for KRUZ’s underperformance.”

The trackers have proved popular. But without quicker, more up-to-the-minute disclosures, investors won’t ever be able to perfectly copy lawmakers’ trades — and anti-corruption advocates will have a harder time pinning down whether a trade was problematic, James Kardatzke said.

Because of this, some members of Congress have come to believe that the decade-old Stock Act is insufficient to restore Americans’ trust that lawmakers aren’t using their access to information for profit.

The penalties for those who violate the law are minimal: Members who are late to disclose stock activity, or sales and purchases of cryptocurrencies, generally face a $200 fine prescribed by the Stock Act. Rep. Pat Fallon (R-Tex.), who failed to disclose 122 transactions valued between $9 million and $21 million in 2021 in a timely manner, paid $600 in late filing fees and corrected the record though he refused to cooperate with the review conducted by the Office of Congressional Ethics.

More problematic, in the view of ethics watchdogs and people familiar with the ethics process in Congress, is that enforcement of the Stock Act lacks teeth and relies entirely on self-reporting.

“There does not seem to be much evidence of the Stock Act being violated, but on the other hand, anyone who truly wanted to violate the Stock Act with any degree of sophistication would be able to do it simply by not reporting it on your financial disclosures,” said a person involved with ethics investigations in Congress who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss a sensitive and ongoing matter.

An effort to ban lawmakers and their families from owning individual stocks stalled out after Pelosi declined to bring a bipartisan change proposal to the floor at the end of her House speakership in 2022, claiming that she didn’t have the votes to pass it.

“It’s already hard for many members to raise a family and maintain homes in two cities on their salaries,” a senior congressional aide explained of member opposition to a ban, speaking on the condition of anonymity to talk candidly. “If you make it impossible for a member’s spouse to take a job that includes stock-based compensation, that is another burden that can drive talented people away from public service.”

That has not deterred a string of unusual pairings of politicians, including Matt Gaetz (R-Fla.) and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) in the House and Josh Hawley (R-Mo.) and Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.) in the Senate, from introducing bills that would place stricter limits on congressional trading.

Rep. Abigail Spanberger (D-Va.), who is leaving Congress in January to run for governor, has been working closely with Rep. Chip Roy (R-Tex.) on another bill, the Trust in Congress Act, which would require members, their spouses and dependent children to put certain investment assets into a blind trust during their term.

Spanberger and Roy are strategizing how best to advance the bill and have discussed the possibility of trying to force a vote on the House floor before the end of this Congress.

“Transparency has created more questions than answers,” Spanberger said, referring to disclosures mandated by the Stock Act. “So now we have a situation where it actually looks like maybe there’s bad behavior when maybe there isn’t — or maybe there is.”

Interest in the bill ebbs and flows “based on the bad or quizzical behavior of our colleagues,” Spanberger said.

Banning lawmakers from owning stock is popular: Eighty percent of voters support a ban on stock ownership by members of Congress, the president, vice president, Supreme Court justices and their families, a poll released last year by the University of Maryland’s Program for Public Consultation found.

“There’s no reason we can’t address it,” Roy said in an interview. “It’s not going to be partisan. It’ll be split, and there will be Republicans who are for or against it and Democrats for it or against it.”

Spanberger lobbied House Speaker Mike Johnson (R-La.), the rare member who disclosed no assets in his most recent financial disclosure report, to address the issue at the start of his speakership.

Johnson did not respond to a request for comment. “Mike understands that there’s a problem,” Roy said. “We’re just trying to work through on a bipartisan basis how we can address it.”

Under current law, members rarely pay a real price for trading-related scandals.

The Office of Congressional Ethics concluded in 2021 that there was “substantial reason to believe” that the wife of Rep. Mike Kelly (R-Pa.) used nonpublic information obtained through her husband’s official duties to purchase stock in an Ohio steelmaker. OCE investigators found that Victoria Kelly purchased stock in Cleveland-Cliffs a day after her husband learned that Donald Trump’s Department of Commerce was set to grant trade protections to the company.

Then-Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross informed the Cleveland-Cliffs CEO on April 28, 2020, that the department’s actions would potentially help his company, prompting Cleveland-Cliffs to keep its operations in Mike Kelly’s district open. On April 29, Victoria Kelly made her first individual stock purchase in almost a year, buying between $15,001 and $50,000 in Cleveland-Cliffs stock.

But three years after the ethics office referred what some legal experts deemed a “textbook” case of trading off nonpublic information to the House Ethics Committee — the entity with the power to hold a lawmaker accountable for wrongdoing — the committee has yet to issue a determination as to whether a violation occurred. Tom Rust, the chief counsel and staff director of the committee, declined to comment on the status of the investigation. Mike Kelly’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

In a hyperpartisan environment with threadbare majorities in both chambers, the members of the House Ethics Committee have little incentive to hold other members accountable. The Senate faces even less pressure to investigate its members: It lacks an independent ethics enforcement body like the Office of Congressional Ethics, which has jurisdiction only over the House.

The Senate Ethics Committee has not issued a disciplinary sanction against a senator in over 15 years, even after a stock-trading scandal roiled the upper chamber. Sens. Richard Burr (R-N.C.), Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.), James M. Inhofe (R-Okla.) and Kelly Loeffler (R-Ga.) came under scrutiny at the start of 2020 after they dumped vast stock holdings ahead of the coronavirus-induced market plunge. Neither the Senate Ethics Committee nor the Justice Department, whose investigators launched probes into the stock sales, pursued charges.

The “clear exoneration by the Department of Justice affirms what Sen. Loeffler has said all along — she did nothing wrong,” a spokesperson for Loeffler said at the conclusion of the investigation, adding that “she and her husband acted entirely appropriately and observed both the letter and the spirit of the law.”

But ethics experts have argued that the problem with lawmakers’ stock trading habits goes beyond the legal issue of insider trading, noting that even the appearance of improper trading can damage the public’s already record-low trust in lawmakers and government.

Members of Congress might not clear the high legal bar for insider trading, which would require making a trade based on material, nonpublic information. But they might still trade on information that the rest of the public doesn’t have meaningful access to, said Marsco of the Campaign Legal Center.

Some members routinely engage in trades that critics see as posing actual or potential conflicts with their committee assignments, where members often are privy to nonpublic — or even classified, sensitive, privileged or otherwise restricted — information. And some have gotten a lot richer — in part due to the gains made through the stock market — during their time in office.

Several trackers have noted that Sen. Markwayne Mullin (R-Okla.) has in recent months disclosed trades of companies that have business before the committees he sits on. Mullin’s net worth has increased from roughly $5.9 million when he was elected to Congress in 2012 to an estimated $63.66 million today.

But Mullin’s case highlights the complexity of the issue. “Over 2 years ago, Sen. Mullin sold several of his companies,” a spokesperson for Mullin wrote in an email. “Any attempts to link an increase in net worth purely to investments outcomes, which are independently managed by a third-party operator, are completely inaccurate.”

Ideally, Mullin and other members of Congress who own stocks would put them in a blind trust, said Kedric Payne, former deputy chief counsel of the Office of Congressional Ethics, who now serves as the vice president of the Campaign Legal Center.

“That way, there’s no way for you to direct your broker to sell that defense contractor stock because you don’t even know you own it,” Payne said.

But the public’s perception of members’ conflicts of interest is the most important issue, Payne added.

“We are now at a new level where the members no longer have to be insider traders to profit — we are at a point where merely publishing what trades a member buys means the price of that stock goes up because other people are following their lead,” he said. “You have a problem that’s very hard to erase.”