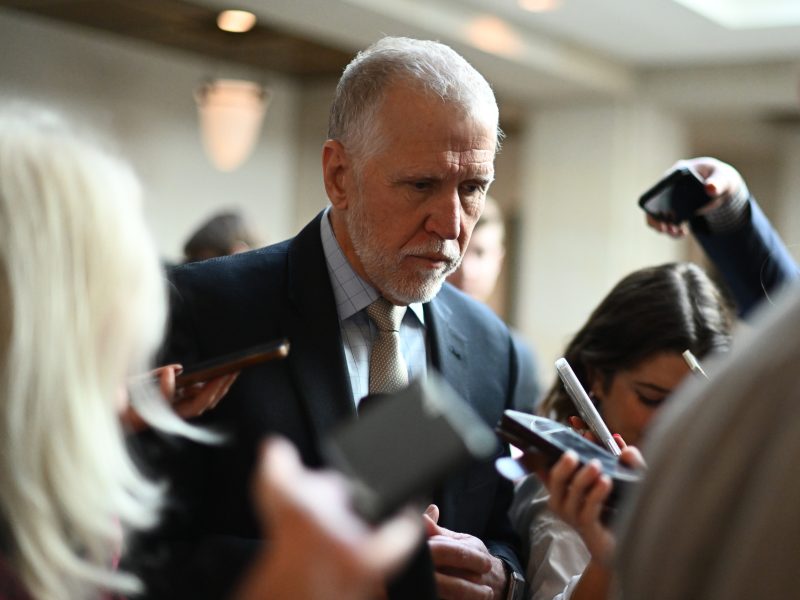

Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.) on Tuesday grew despondent at the idea of leading a delegation to the upcoming Munich Security Conference as Congress had yet to approve additional money to help back Ukraine’s war against Russia.

Whitehouse summed up his feelings in one word: “Crappy.”

By Thursday, however, the tide had shifted and a bipartisan collection of 67 senators voted to open debate on a $95 billion security measure, with almost two-thirds of that directed toward Ukraine. A final vote could come by midweek just as roughly 30 senators are slated to head to Europe.

Yes, the deal could still fall apart in the Senate and its prospects in the increasingly nativist House remain up in the air, but Whitehouse practically had a bounce in his step after that vote.

“We may be less empty-handed, TBD,” he said.

The annual security conference has long served as an annual show of cross-Atlantic unity, providing each party’s internationalist wing a chance to tout its vision of U.S. leadership.

Last year’s security conference saw record-high numbers of U.S. lawmakers there to show unity against Russian President Vladimir Putin, telling their European allies not to worry about those vocal Republicans who were opposed to additional funding to Kyiv.

“I think there’s been way too much attention given to a very few people who seem not to be invested in Ukraine’s success,” Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) said last February before heading to Munich.

But those “very few people” grew their ranks, and for the past four months they have bottled up efforts by the Biden administration and traditional security hawks in Congress to replenish Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelensky’s weaponry.

The bleeding of political support has all come from one side of the aisle.

In May 2022, 39 GOP senators joined 47 Democrats in voting for a $40 billion security-and-humanitarian aid package for Zelensky, with just 11 Republicans voting no.

On Thursday, just 17 Senate Republicans, barely a third of their conference, voted with 50 members of the Democratic caucus to move forward on debate on the national security measure. On, Friday one more Republican voted yes on a procedural motion to advance the bill.

Sen. Thom Tillis (R-N.C.), one of those voting yes, warned that his fellow Republicans needed to remain strong in their support for Ukraine or else their party will become the face of surrender to Putin.

Over the next few days the debate would end one of two ways, Tillis said. “A sufficient number [vote yes] to send it to the House, or Republicans ultimately owning the message from the U.S. Senate that there’s not enough of us to support Ukraine aid.”

This Senate debate comes just after the European Union reached a unanimous deal among all 27 member nations to send $54 billion to shore up Ukraine’s government services, providing a rejoinder to far-right critics in Congress who regularly say the E.U. doesn’t provide enough support for its own security.

Many of the 31 GOP opponents in the Senate do not want to provide funds for Ukraine under any circumstances, while some said they would only vote to do so if President Biden accepted their exact prescription for shoring up the U.S.-Mexico border’s migrant crisis.

Some Republicans gave conflicting statements that served as political head-spinners.

On Tuesday, as a bigger security package fell apart because of partisan divisions over border rules, Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) stuck by his long-held view of wanting to defeat Putin at all costs.

“If we fail on the border, we put our country at risk. There’s no use letting the world fall apart, because Putin winning in Ukraine doesn’t solve any of our problems. It makes all of our problems worse,” Graham told reporters.

For several years Graham has served as the co-host of Whitehouse’s group, dubbed the “McCain delegation,” in honor of the late Sen. John S. McCain (R-Ariz.), a legendary presence who used his last several trips to Munich to reassure allies that Donald Trump’s world view had not taken hold in Washington.

On Tuesday, Graham was ready to strip the contentious border provisions and just pass the funds to defend Ukraine, Israel and Taiwan. “No matter how you feel about the border, the problems of Ukraine, if not managed well, will make every problem we have at home worse,” he said.

Yet two days later, he reversed his position, voted against moving to debate the Ukraine-Israel-Taiwan package and joined the ranks of MAGA senators who want to close the border.

“I enthusiastically support Ukraine, Taiwan and Israel, but as I have been saying for months now, we must protect America first,” Graham said in an official statement.

Later Thursday, he got into a heated Senate floor debate with Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (I-Ariz.), who helped lead the border proposal negotiations. Graham mocked Sinema’s group for a “half-assed effort” at reaching a border compromise, without acknowledging that he and his staff played regular roles in the talks.

Then he held up a large poster-board with a social media post from Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk, who suggested Ronald Reagan would be “turning in his grave” over the attitudes of today’s Republicans.

“Shame on you. To the prime minister of Poland, I could care less what you think,” Graham shouted.

This is exactly the opposite message that Tillis, Whitehouse and others want to bring to Munich.

“There are people in Ukraine right now in the height of their winter, in trenches, being bombed and being killed,” Tillis said. “The signal from the United States about whether or not we’re going to be there is not only important to the morale of those warfighters that are doing that every single day for the last two years, but also for the 50-some countries that are also part of this coalition.”

Sen. Chris Coons (D-Del.) said he expects to hear the same question from European counterparts next weekend: “Can we count on you?”

But those GOP voices are increasingly drowned out by the newcomers, such as Sen. J.D. Vance (R-Ohio), who won in 2022 after he refashioned himself from Trump critic to all-in MAGA theorist.

Vance plans to deliver that blunt message when he goes to his first Munich conference. “First of all, this war is in your direct backyard,” he said, followed by accusing Europeans of “turning NATO effectively into a welfare client of the United States.”

Of the 17 Republicans who took office after Trump won the presidency, just two voted to advance the Ukraine-centered security package: Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah), who, at 76, had already served as a governor and his party’s 2012 presidential nominee before joining the Senate five years ago; and Sen. Markwayne Mullin (R-Okla.), a leadership ally elected in 2022.

Some Republicans doubt the dire predictions that, if the U.S. funding dried up, Russia could crush the smaller nation.

“I don’t think Russia has the capability to roll through and take all of Ukraine, much less hold it. Before we got aid to Ukraine [in 2022], the Russians couldn’t do that,” Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.), the top Republican on the Senate Intelligence Committee, said Thursday. “I think what it does do is force a negotiated settlement much more favorable to Putin, because he’ll feel emboldened and stronger.”

Other Republicans say that is naive.

“There are pivotal times in our nation’s history when what we do in this chamber really matters,” Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine), who co-wrote much of the security package, said in a floor speech. “How we vote may well determine whether people live or whether they die; whether men and women live under the dictates of an authoritarian regime or as free people in a democratic nation.”

Tillis, a member of the Armed Services Committee, said Russia’s long-term plan has been to wear down American support for the war and unravel international backing for Zelensky.

“Us leaving here with the Senate failing to take this up, is exactly what Putin hopes happens this weekend,” he said. “And I’m going to do everything I can to prevent it.”

All of this could end up nowhere in a very conservative House, where GOP leaders move in lockstep with Trump. But Whitehouse remained optimistic that Senate leaders were working to include measures that some House Republicans want and hopeful that an even larger vote could come within a few days of the Senate’s final passage of the security measure.

That would make for a much more enjoyable trip across the Atlantic Ocean.

“I think the Munich Security Conference delegation won’t have loads of egg on its face,” Whitehouse said.