Nearly four years after 43-year-old William Green was fatally shot while handcuffed behind his back, the second-degree murder trial for the Prince George’s County police officer charged with pulling the trigger began Monday.

The officer, Cpl. Michael Owen Jr., has been jailed since the fatal shooting in January 2020, when police say he shot Green six times as the man sat in the front seat of his police cruiser. Owen’s own department arrested him less than 24 hours later, the first time a county officer had been charged with murder in connection with actions taken while on duty.

Jury selection started in Prince George’s County Circuit Court on Monday morning for the case, which has ignited calls for police reform in the majority-Black Washington-area suburb in Maryland, where the police department has long had a fraught history of excessive force and misconduct.

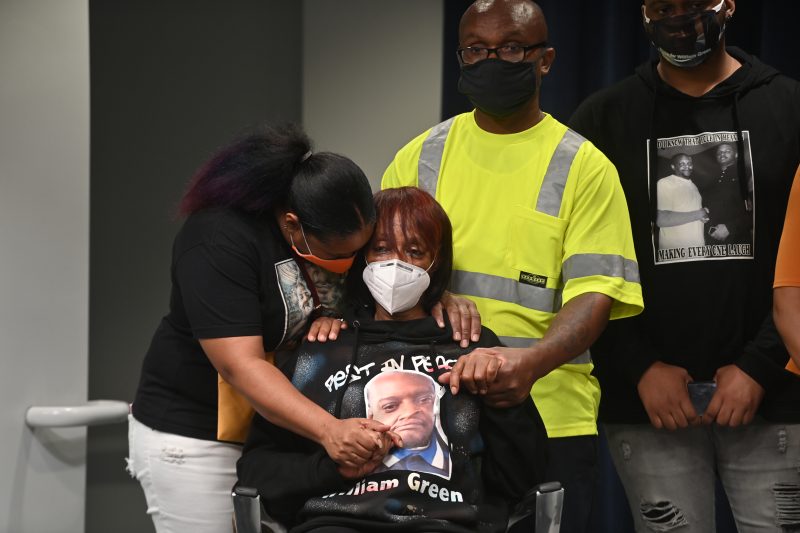

Since Green was killed on Jan. 27, 2020, his family has won a $20 million settlement from county officials and upended a potential plea deal for Owen earlier this year after publicly expressing their disapproval because they wanted the details of the case to be exposed in court.

Before the fatal shooting, Owen had been accused of using excessive force and had sought workers’ compensation for psychological difficulties stemming from a fatal shooting earlier in his career, information that should have been reported to supervisors or triggered intervention through the police department’s early-warning system. But that did not happen.

Green, of Southeast Washington, was a father of two and a Megabus luggage loader whom family called “Boo Boo.” On the night he was killed, police received a 911 call about a man driving a Buick that had struck several vehicles. Authorities eventually found the car in Temple Hills, Md. Green was asleep inside.

Owen removed Green from the car, cuffed his hands behind his back and placed him in the front seat of a police cruiser to wait for a drug recognition expert, according to police records and interviews. A few minutes later, authorities said, Owen shot at Green seven times, with six shots hitting the man. The wounds, Green’s family said, were on both sides of his torso.

Owen was not wearing a police-issued body camera at the time of the shooting. The officer told authorities that Green reached for his firearm and that he feared for his life. Thomas Mooney, Owen’s attorney, has said in the past that authorities pressed the second-degree murder charge after a “rushed” investigation.

But prosecutors have said there is no evidence that Green posed a serious threat.

The case became a turning point for police reform in Prince George’s County but never captured the nation’s attention in the same way that the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police did in the summer of 2020, sparking widespread racial-justice protests.

For Green’s family, the reason is simple: The officer who killed Floyd is White. The officer who killed Green is Black.

Still, local police accountability advocates worked with Green’s family and Baltimore-based civil rights attorneys William “Billy” Murphy and Malcolm Ruff to push Prince George’s police to reform their systems. The county paid Green’s family a $20 million settlement after they filed a federal wrongful-death lawsuit, believed at the time to be among the nation’s largest one-time settlements involving someone killed by law enforcement. (Floyd’s family was later awarded $27 million from the city of Minneapolis.)

During the news conference announcing the Green family’s settlement in late 2020, County Executive Angela D. Alsobrooks (D) said officials were “accepting responsibility” for the mistakes that led to Green’s death. She created a police reform working group and vowed to advocate for police reform measures at the state level.

“Police are given by this community an awesome and tremendously difficult responsibility of protecting life,” Alsobrooks said at the time. “They are also likewise given an authority that is not shared by anyone else in this community, and that is the authority to take life. … When that trust is abused, it is necessary to take swift and decisive action.”

It has taken prosecutors nearly four years to bring their case before a judge. The trial was first delayed by the coronavirus pandemic, but even after the courts in Maryland reopened and criminal trials resumed, delays continued. The trial was scheduled for March 2021, then rescheduled to March 2022, then pushed again to February.

Just days before the trial was scheduled to begin, though, prosecutors offered Owen a plea deal that would have reduced the officer’s charges from second-degree murder to voluntary manslaughter and dramatically cut back a potential punishment, The Washington Post reported. Green’s family had met with prosecutors on the anniversary of the date Owen was first charged to discuss the plea offer and expressed concern that the deal could have made the officer eligible for parole within a few years.

Prosecutors made the offer, according to court records, and Owen accepted.

Plea deals, which are common in courthouses nationwide, are not final until a judge accepts them, and the details rarely become public before they are discussed in open court. But Green’s family went public with their disapproval — and Judge Michael Pearson threw out the deal days later, telling prosecutors in court that they had “dropped the ball” in the case.

He delayed the case a final time because neither the prosecution nor the defense was prepared to go to trial.

Ahead of the shooting, the department missed opportunities to steer a struggling and errant officer back on course, a Post investigation in 2020 found.

Owen had triggered the agency’s early-warning system by using force twice in quick succession the previous summer. But it took months for the system, which relied on information being compiled by hand and entered into a database, to create the flag, police officials said. Owen’s supervisors weren’t formally notified until the month he killed Green, and they had not taken action.

In two other 2019 incidents, videos showed Owen with his hands on the necks of people he arrested. One of those incidents came less than a month before Green’s death.

Other Prince George’s residents who encountered Owen over the years also had accused him of brutality and a lack of professionalism. Several who were arrested by Owen, and accused of aggressive behavior toward him, had charges dropped because the officer did not show up for court proceedings — another sign of trouble.

Experts who spoke to The Post said the sluggish pace of the early-warning system jeopardized both officers and civilians like Green. Former Prince George’s County police chief Hank Stawinski — who ordered Owen arrested after the shooting — told The Post that he understood that the system was too slow and had been working to upgrade it.

Owen’s supervisors also were unaware that he had sought workers’ compensation for psychological difficulties stemming from a fatal shooting early in his career, department officials said, even though Owen was supposed to notify them. This meant that while some parts of the county bureaucracy were aware of the claim, Owen’s supervisors — according to the department — were not.

Opening statements in the trial are expected to start Tuesday.