BEREA, Ohio — Ashton Grant got his NFL start on the lowest rung of the proverbial coaching ladder, as a yearlong fellow with the Cleveland Browns. His job, at least in the beginning, was simply to listen and learn.

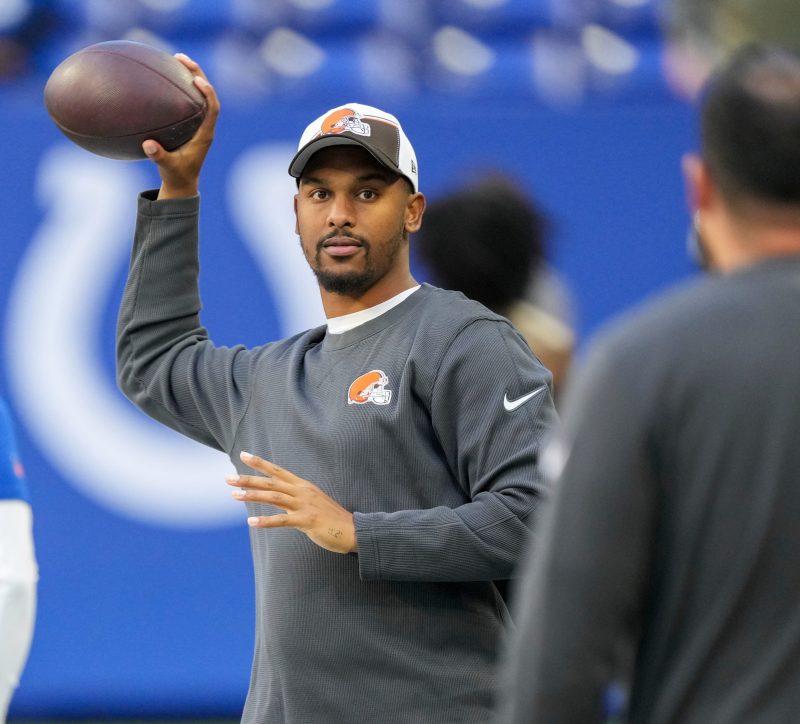

In the three years since, Grant has already been promoted twice: to offensive quality control coach, then to an offensive assistant working with the quarterbacks. At 27, he is still the youngest on-field coach on the Browns’ staff and one of the youngest in the NFL, period. His goal is to one day become an offensive coordinator.

“Sometimes I teeter on the line, if I want to become a head coach or not,” Grant said with a smile. “You’re in the public eye, you’re kissing babies — I don’t know if I want to do all that.”

Maybe that will change with time, he added. Maybe it’s just that offensive coordinator seems closer right now to the Xs and Os of the game, which he’s always loved. Or maybe it feels like the role is more within his reach — even though history suggests that is not, in fact, the case.

A climb that rarely leads to the top

For coaches of color like Grant, who is Black, the road to becoming an NFL offensive coordinator has always been confoundingly steep. Last year, there were four Black offensive coordinators in the league, three of whom were fired or not retained by the end of the season. This year, there are just three — which, according to USA TODAY Sports research, is the league’s annual average since the 2003 implementation of the Rooney Rule that requires teams to interview diverse candidates for vacancies at key positions.

The shortage of Black offensive coordinators has become especially glaring in recent years, as overall diversity within NFL coaching staffs has grown. According to USA TODAY Sports research, there are more coaches of color in on-field roles than ever before and more coaches of color getting opportunities on the offensive side of the ball. But that hasn’t changed the situation at the top of offensive staffs — at least not yet.

‘It’s a hard climb for a Black guy,’ said Lionel Taylor, who became the first Black offensive coordinator in NFL history when he assumed the role with the Los Angeles Rams in 1980.

Now 88, he likened the league’s progress to a traveler heading from New York to Los Angeles and winding up in Phoenix. Getting closer, he said, is not the same thing as getting there.

‘People say, ‘Well it was a long time, things are so much better,’ and this and that,’ he continued. ‘That’s an excuse. You say you’re climbing the ladder but you haven’t made it. That’s the way I look at it.’

A position that’s ‘plagued’ the NFL

While hiring head coaches in the NFL often receives the most public scrutiny, the trends at offensive coordinator are just as striking — and equally important considering the disproportionate number of white coordinators who have become head coaches over the past 10 years.

As part of its NFL coaches project, USA TODAY Sports found:

► The NFL, whose player pool historically is between 60% and 70% Black, has never had more than five Black offensive coordinators in a single season.

► Over the past 20 years, NFL teams have hired an average of nine white offensive coordinators for every Black offensive coordinator.

► In the decade from 2013 to 2022, only 12 Black men worked as full-time NFL offensive coordinators — the same number of Black men who worked as head coaches during that time.

‘That position has plagued us,’ NFL executive vice president of football operations Troy Vincent said. ‘A lot of that is from the false narratives of who these men were and what they were capable of doing — these myths that exist.

‘We’ve still got a lot of work to do here. But the efforts of building, focusing in on building the pipeline, we believe will have some long-term implications.”

Jonathan Beane, the NFL’s senior vice president and chief diversity and inclusion officer, said the league office considers improving diversity at offensive coordinator to be a key strategic goal. It’s why the NFL announced last spring it will begin requiring each team to hire a woman or a member of an ethnic or racial minority to coach on the offensive side of the ball, among other initiatives intended to get more people of color into offensive coaching rooms.

The league is betting that more coaches of color in entry-level positions will cause diversity at offensive coordinator — and, in turn, head coach — to eventually climb. But it hasn’t happened this season, and those who follow the issue closely acknowledge that it might not happen any time soon.

“That’s sort of the long path, to getting more numbers at the head coach position,” said Rod Graves, executive director of the Fritz Pollard Alliance. “I’m not suggesting that there needs to be a more detailed or even a different approach. But the path that the league has focused on is going to take some time to get the results.”

Grant’s path from Assumption to the NFL

In conversations about coaching diversity in the NFL, league officials and experts often reference “the pipeline” of diverse coaches working their way up the ranks.

It’s a pipeline already filled with dozens of sharp up-and-coming coaches like Grant.

Like many of his coaching peers, Grant said he originally dreamed of making it to the NFL as a player. But after a successful career as a wide receiver at Division-II Assumption College, during which he broke multiple school records and earned two all-conference nods, Grant received only a handful of invites to NFL rookie mini camps, which ultimately led to nothing. A brief foray into the now-defunct Alliance of American Football also fizzled.

“I saw the writing on the wall, of what my playing career would’ve been,” Grant said.

So rather than toiling on practice squads or bouncing around lower-level leagues, Grant decided to go back to school and finish his degree. He said he spent just two months away from football before getting an itch to return, even if that meant moving to the sidelines. A conversation with his college coach, Bob Chesney, led to Grant’s first coaching gig, as a volunteer special teams quality control coach on Chesney’s new staff at Holy Cross.

It didn’t take long for Grant to have an impact, Chesney said.

“His ability to relate to these players, I think, is probably one of the things that will be one of his strongest attributes,” Chesney said. “His maturity was through the roof, and his ability to connect and empathize with everybody also stood out to me. … He wasn’t afraid to speak his mind.”

A year later, in 2020, Grant got his first opportunity in the NFL, spending a few weeks with the Browns as part of the Bill Walsh fellowship program — a long-running, leaguewide effort to give diverse coaches a chance to build connections in the league.

Little did he know that Cleveland also wanted to create its own fellowship program, a more substantial, yearlong position named after former Browns lineman Bill Willis, one of the first Black players in the league’s modern history.

In their search to find “a rising star,” Browns head coach Kevin Stefanski said Grant, then 24, stood out from other applicants because of his desire and dedication — as evidenced, among other things, by his work as a low-level special teams coach at a Football Championship Subdivision school.

“You have to love football to coach and not get paid a bunch of money at all and just grind,” Stefanski said. “And he clearly had that in him as a young coach.”

Lack of diversity on offense ‘a mystery’

When the Browns introduced the Bill Willis Coaching Fellowship, they noted the position would work exclusively on the offensive side of the ball. It’s no secret why.

While the league has made significant strides in coaching diversity over the past five years, data shows those gains have come disproportionately on the defensive side of the ball. According to USA TODAY Sports research, 55% of all defensive coaches in the NFL this season are people of color, including half of the league’s defensive coordinators. On offense, meanwhile, coaches of color hold 40% of the roles, including just 12.9% of the offensive coordinator jobs.

“Why we are getting more opportunities on the defensive side, as opposed to the offensive side, is still a bit of a mystery,” Graves said. “I think it certainly starts with recognizing that there’s more talent in the pipeline than we choose to recognize.”

Graves, the former general manager of the Arizona Cardinals, applauded the NFL for helping more Black coaches get a foot in the door through its offensive assistant initiative, which requires each team to hire an assistant who is a woman or part of an underrepresented racial or ethnic group, and provides funding for that role. But he believes the focus now must be on helping those young coaches progress through the ranks.

Part of this, he said, comes down to improving a hiring process in which the success of a coach’s previous team is often put above their knowledge, skills and experience.

“At this point, I think we’re leaving a lot of good talent behind — and that’s regardless of color,” Graves said. “We’re not optimizing our ability to point to the best that the league has to offer.”

The other piece is development, and that’s where coaches like Stefanski come in.

Before the Browns hired him, Stefanski spent 14 seasons with the Minnesota Vikings, working his way up from the head coach’s assistant to offensive coordinator. He said he was given opportunities as a low-level coach to grow into new roles and coach different positions — and his objective now is to provide the same opportunities for young coaches of color, such as Grant.

“Until this gets better, we have to be intentional about it,” Stefanski said when asked about the lack of diversity among NFL offensive coordinators. “We need to develop young Black coaches.”

One past Bill Willis fellow, Israel Woolfork, has already landed a quarterbacks coach job after following former Browns assistant Drew Petzing to Arizona this year. The Browns also have one of the league’s highest-ranking female coaches on their staff in assistant wide receivers coach Callie Brownson. Stefanski originally hired her as his chief of staff in 2020.

‘These initiatives allow for young men, and now young women, to just be in the room to learn,’ Vincent said.

‘It allows exposure for these young (coaches) to be exposed to play-calling, organizational structure on the offensive side of the ball. We didn’t have that five, six years ago. Today, we do.”

‘You have to get in the quarterback room’

Grant said he has taken on more responsibility in each of his four seasons with the Browns — from breaking down tape, to helping draw and chart passing plays, to leading position group meetings and giving presentations on opponents’ schemes and tendencies to the entire offensive staff.

He’s also spent each year with a different position group, moving from running backs to wide receivers to tight ends and, most recently, quarterbacks. Offensive coordinator Alex Van Pelt oversees the quarterback room, but Grant is effectively the assistant position coach.

“I think if you want to coordinate an offense, you have to get in the quarterback room,” Grant said. “Because that’s the only room where you’re fully engulfed in what’s going on.”

The statistics certainly bear that out. Of the 31 offensive coordinators in the league this year, 26 either passed through the quarterback room or previously held the title of “passing game coordinator.”

The problem is that, for coaches of color, these positions have also historically been the hardest to get.

In a wide-ranging report last year, USA TODAY Sports found Black coaches are still largely left out of springboard roles, like coaching the quarterbacks, and instead confined to working with position groups, such as running backs, that offer slimmer hopes of advancement — a trend one expert described as “positional segregation.”

Taylor, who won two Super Bowl titles as an assistant coach with the Pittsburgh Steelers, said the same sentiments existed when he became an NFL assistant decades ago. There have long been preconceived notions not only about the positions Black men can play, he said, but also ones they should coach.

“I knew it was a hard wall to climb,” Taylor said of his path to the coordinator spot. “You knew there was discrimination there. A Black person was not going to be in the spotlight calling the plays, snapping the ball — or playing quarterback.”

In May 2022, the NFL took arguably its most significant step to date to address this issue by expanding the Rooney Rule to require that teams interview a diverse candidate for quarterback coaching vacancies, in addition to coordinator and head coach roles.

According to USA TODAY Sports research, there is one more quarterback coach of color in the NFL this year than there was a year ago, and three more assistant quarterbacks coaches of color, including Grant.

‘The numbers don’t lie: We’re not where we need to be on the offensive side of the ball, in particular when we look at positions like QB, O-Line, tight end and offensive coordinator,’ Beane said.

‘We always feel that we want to be well-positioned not only today but three years from now, five years from now, eight years from now. And to do that, you’re going to have to build, brick by brick, the foundation — in terms of a pipeline of talent — on that side of the ball, in those positions.’

Nepotism, cronyism and the trust factor

Grant said he doesn’t pay much attention to all the stats on coaching diversity and hiring trends in the NFL, though he can’t help but follow the career paths and successes of guys like Pittsburgh Steelers head coach Mike Tomlin, whom he called ‘inspirational.’

He said he hasn’t given much thought to how the league’s efforts might impact the trajectory of his own career.

“I haven’t looked at the numbers like, ‘Oh, they’re talking more about hiring Black people so maybe it’s good for us,’” Grant said. “I haven’t looked at it that way. I’m just excited that people are getting more opportunities.”

Perhaps the most important aspect of all of this, he added, is relationship-building. ‘People understand who I am as a worker,’ he said, ‘not just a one-page resume on their desk.’

Vincent pointed out that, unlike owners hiring head coaches, the decision to hire a coordinator or position coach usually rests with the head coach. And that makes it all the more important, in his view, that Black coaches get in the offensive room, where they’re able to prove their value.

‘Nepotism, cronyism, this is where it sits,’ Vincent said. ‘There’s a trust factor. There’s hiring people that you are familiar with, that you’ve either coached with or your buddy has shared with you. … The Black coach just hasn’t had that opportunity, because he’s not in the room to make those decisions at that level.’

The most recent hiring cycle offers just one example. While half of NFL teams hired a new offensive coordinator prior to this season, only three of those 16 vacancies were filled by Black men: Thomas Brown in Carolina; Brian Johnson in Philadelphia; and Eric Bieniemy in Washington. A fourth hire, Tampa Bay Buccaneers offensive coordinator Dave Canales, is Latino-American.

In contrast, more than half the league’s open defensive coordinator jobs were filled by coaches of color — including Minnesota Vikings defensive coordinator Brian Flores, who is suing the NFL and several of its teams for discrimination.

The question, over the next five to 10 years, is whether young, hungry coaches like Grant will help alter these trends.

When asked where he sees himself a decade from now, Grant said he hopes whatever he’s doing, he’s making his family proud, and that his recently-born daughter still thinks he’s ‘pretty cool.” Career-wise, he aspires to either be an offensive coordinator or a quarterbacks coach ascending to that spot.

Graves was asked if, given the NFL’s history in hiring offensive coordinators of color, there should be optimism that Grant will get there — or, at the very least, get a fair shot.

“If this young man is developing and working at it and puts into it all that he can, he has a chance,” Graves said. “And his chances are better today than they’ve ever been.”

Contact Tom Schad at tschad@usatoday.com or on social media @Tom_Schad.