Labor strikes and contract negotiations have recently been in the news more than they have been in years.

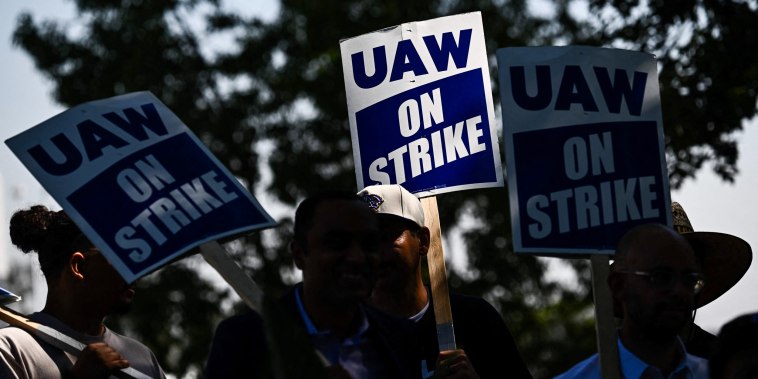

The United Auto Workers went on strike Sept. 14 after the UAW and Detroit’s Big Three, General Motors, Ford and Stellantis, couldn’t agree with the union on the terms of a new contract.

And over the past few months, Hollywood was wracked by a rare double strike as writers hit the picket lines in May and actors joined them in July. One of those strikes ended in late September, as the Writers Guild of America agreed on contract terms with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, which represents film and TV production companies.

The actors’ union, SAG-AFTRA, remains on strike.

One common point between the two high-profile strikes is the trajectory of technology in the auto and entertainment industries. The UAW has expressed concerns about the possibility that electric vehicles, which are simpler compared with those powered by gasoline, will be assembled by fewer workers. Major issues for the Writers Guild have included the size of writers’ rooms on scripted shows, and the producers’ ability to use AI to create scripts or stories.

Even before those strikes, work stoppages in other industries were making headlines, too. In July, 340,000 UPS workers came close to a strike before the Teamsters union agreed to a new contract that secured an average pay increase of 48% over five years.

A union that represents more than 15,000 American Airlines pilots also threatened a strike before it secured a significant pay bump.

“Labor has maybe just had enough,” said Rick Eckstein, a professor and sociology program director at Villanova University. “They had been giving up benefits and wages for 30 to 40 years almost across the board.”

Eckstein told NBC News that unions and many other workers watched their pay and benefits shrink after the 2007-08 financial crisis and the subsequent Great Recession. They expected, he said, that things would change as economic conditions improved. Instead, U.S. workers watched corporate profits and executive compensation soar while their own pay slipped relative to inflation and the cost of living.

Then came the pandemic

Covid arrived, with many groups of “essential workers” risking their lives during the pandemic. But as inflation spiked, job gains slowed, and parts of corporate America grew worried about a recession as they saw companies starting to cut jobs.

According to Bloomberg Law, new union-negotiated contracts gave workers a 7% first-year increase in pay in the first quarter of this year. That’s the largest on record since 2007, and Bloomberg speculates that it’s likely the largest ever.

Part of the wage increases can be attributed to expanded corporate profits in the wake of the pandemic, and to inflation.

‘If this wave increases it’s going to reduce that gap between executive or wealthy people or wealthy companies and the workers who are doing the labor,’ said Eckstein.

‘That’s always what’s happened historically.’

Eckstein and Patricia Anderson, an economics professor at Dartmouth, agree that the strong labor market is a major factor in what’s happened.

‘Workers felt like they had a lot of power, they were in the driver’s seat,’ Anderson, who’s also a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research, said. But she’s skeptical that widespread social change is in the offing. That’s partly because so few people are union members today.

Unions on the decline

Over the past 40 years the rate of unionization for workers has fallen to 10% from 20%, and even though the population of the U.S. and the labor force have grown, the number of overall union members has fallen to 14.3 million from 17.7 million.

Workers in the public sector, like teachers, are unionized at far higher rates than private sector employees. About 33% of government employees are in unions — that includes police, firefighters and teachers — compared with 6% of other workers.

‘You’d need a lot more unionization for this to have much of an impact on the economy at large,’ Anderson said of labor movements broadly.

Union membership had gone into a gradual decline as manufacturing, transportation and construction became smaller parts of the economy. Other contributing factors include deregulation, offshoring, technology and a shifting political landscape — one where, over the decades, laws and regulations have changed in ways that make it harder to unionize.

On top of that, Republicans have generally been hostile to unions in recent decades, the most famous example being President Ronald Reagan’s decision to fire 11,000 striking air traffic controllers in 1981. That step emboldened employers and led to a steep decrease in labor strikes.

President Joe Biden has declared himself as strongly pro-union, to the point that he visited UAW strikers on the picket line last week, a first for a sitting president. And experts agreed that the National Labor Relations Board, the agency responsible for enforcing U.S. labor laws, has been more clearly pro-worker under Biden.

Still, in December Biden signed a bill that blocked a strike by railroad workers by forcing several unions to accept contract terms they had rejected. He said at the time that a strike by railroad workers would have caused an economic catastrophe.

Whether or not there’s a long-term change in union membership, it’s possible that the effects of these demonstrations of worker strength will linger. In late September, nonunionized pharmacists at a group of Kansas City-area CVS stores refused to go to work because they were frustrated the company wasn’t hiring enough staff. The company said it would address the problem.

And unions have long argued that even nonunion shops benefit from their actions, as businesses that have to compete with employers are pushed to offer greater benefits.

‘If you see the Starbucks down the street unionizing you might make things better for your own workers,’ Anderson said. ‘You could see better wages and conditions just in response to the threat that workers will be the ones to organize next.’