Dick Clark, a former college professor who won a long-shot U.S. Senate campaign in 1972, wooing Iowa voters with help from a folksy walk across the state, and who went on to help shape U.S. foreign policy in Africa during a brief but busy single term in office, died Wednesday at his home in Washington. He was 95.

His family announced the death but did not cite a cause.

Mr. Clark, a liberal Democrat, hardly seemed destined for a career making policy on Capitol Hill. Born in his grandmother’s farmhouse in eastern Iowa, he grew up in the back of his parents’ grocery store, where his family hung oil lamps for light and relied on a wood-burning stove and hand-pumped well. He helped pay for his education by baling hay, became one of the first in his family to graduate from college, and joined the faculty at Upper Iowa University in Fayette as a history and political science professor.

But after a few years volunteering in local Democratic politics, Mr. Clark quit academia and moved to Washington, becoming the top aide for newly elected Rep. John C. Culver (D-Iowa) in 1965. When Culver began considering a run for Senate in 1972, Mr. Clark laid the groundwork for his campaign — then ran for office himself after Culver had a change of heart, deciding it would be better to hold on to his House seat instead of taking on a two-term Republican incumbent, Sen. Jack R. Miller.

Mr. Clark had never run for office and was unknown to most Iowa voters. But his campaign gained traction after he started trekking across the state on foot, adopting a tactic that another little-known Senate candidate, Lawton Chiles of Florida, had used to headline-making effect two years earlier. He walked more than 1,300 miles, meeting with hundreds of farmers, shopkeepers, radio broadcasters and newspaper reporters, asking about their lives and answering questions about corn prices and tax plans.

When the results came in, signaling that Mr. Clark had won 55 percent of the vote, he and his team were stunned, according to longtime aide Robert K. Miller. “We had a campaign headquarters in a dirty, dusty little building in Marion, Iowa. People were working for nothing,” Miller said in a phone interview. “Somebody from CBS called, and the next thing I know, there’s a news break that we had won.”

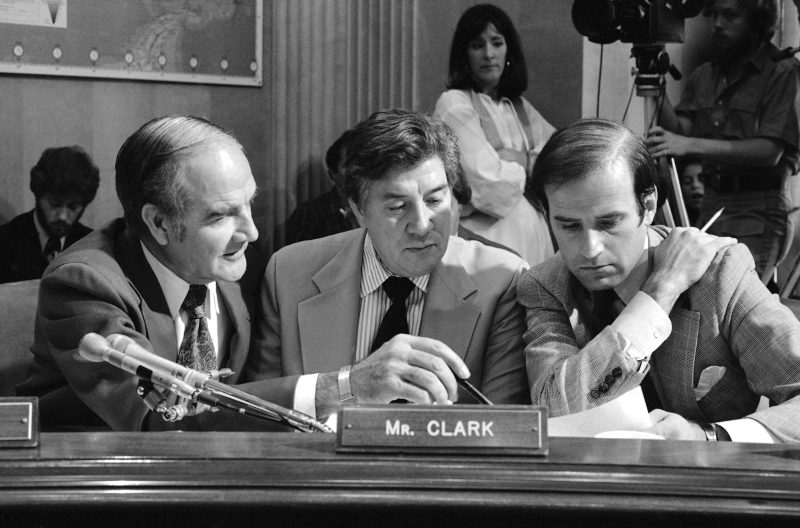

In Washington, Mr. Clark served on the Senate Agriculture Committee and helped create the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. But he was best known for chairing the Foreign Relations subcommittee on African affairs, a role that gave him a platform to speak out against White-minority rule in South Africa and Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe.

Mr. Clark traveled across sub-Saharan Africa, educating himself on policy issues, and met with activists including Steve Biko, a leader of South Africa’s anti-apartheid movement, who was later killed in police custody.

In 1976, he sponsored a measure banning American aid to rebels in Angola, where paramilitary groups were fighting the country’s leftist government with support from South Africa and the CIA. (The ban, which became known as the Clark amendment, was repealed in 1985 under pressure from the Reagan administration.) He later championed a 1977 bill that restored an embargo on Rhodesian chrome, part of an effort to promote a transition toward Black-majority rule in the country.

Mr. Clark’s interest in African policy issues, and especially his support for Black liberation movements, earned him plenty of critics. When he ran for reelection in 1978, he was taunted by Republican challenger Roger Jepsen, a former Iowa lieutenant governor, who labeled him “the senator from Africa.”

Antiabortion activists also targeted Mr. Clark, as did a top South African embassy official who broke diplomatic protocol to get involved in the campaign, asking voters during a visit to Iowa “why their senator finds South Africa such a fine platform, rather than dealing with the real problems this state might have.”

The diplomat’s comments prompted a formal rebuke from the State Department, although foreign meddling in the race apparently continued: After the election, former South African information secretary Eschel Rhoodie claimed that his government provided $250,000 in support of the Jepsen campaign, which denied knowing anything about the alleged funding.

Mr. Clark lost to Jepsen by 3 percentage points. He was soon appointed an ambassador at large by President Jimmy Carter and spent most of 1979 serving as the administration’s coordinator for refugee affairs, working to provide aid and housing for tens of thousands of people fleeing wars and famine in Southeast Asia.

After resigning to work on Sen. Edward M. Kennedy’s 1980 campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination, Mr. Clark became a senior fellow at the Aspen Institute, a Washington think tank. Combining his interests in teaching and politics, he launched a program to educate members of Congress on foreign policy issues, organizing dozens of bipartisan conferences and retreats, including sessions on the politics and history of the Soviet Union, Vietnam and South Africa.

One program, held in Bermuda in 1989, brought U.S. lawmakers together with South African politicians and members of the country’s outlawed opposition. After anti-apartheid leader Nelson Mandela was freed from prison in 1990, Mr. Clark organized a gathering within South Africa, bringing in officials that included Mandela as well as F.W. de Klerk, the country’s last apartheid president.

“Aspen enabled me to help fill one of the most important needs of the U.S. Congress: providing time and opportunity for informed reflection in a bipartisan setting,” Mr. Clark later wrote, according to his family. “People have told me that this was more important than the work I did in the Senate. It may have been the most important thing I’ve done in my life.”

The second of three children, Richard Clarence Clark was born in Paris, Iowa, on Sept. 14, 1928. He served two years in the Army before graduating from Upper Iowa University in 1953. Three years later, he received a master’s degree in history from the University of Iowa.

His first marriage, to Jean Gross, ended in divorce. Survivors include his wife, Julie Kennett Marshall of Washington, whom he married in 1977; two children from his first marriage, Julie Clark Mendoza of Bethesda, Md., and Thomas Clark of Baltimore; a stepson, Stephen Kennett Marshall of Washington; three grandchildren; and two great-grandsons.

Mr. Clark said that for all his foreign policy work in Africa, he fell into the field only by chance, when the Senate Foreign Relations Committee was divvying up its subcommittees. “I was next to last on seniority,” he told Politico in 2013. “When it got down to me, the only thing left was Africa, about which I knew very little. Some would say none. So I just figured: Here’s a chance to learn something.”

His willingness to dive into the field impressed many of his colleagues, including his old boss Culver, who was elected to Iowa’s other Senate seat in 1974. “Dick came to it when there was less political reward,” Culver told Politico. “But he stuck to it.”