DAYTON, Ohio — At the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 82 Hall here in June, Ohio’s senior senator posed for photos with bricklayers. He joked with sheet metal workers. He questioned union worker after union worker: Where do you live? What got you into this trade? How long have you been working in this industry?

This is how Democratic Sen. Sherrod Brown has won three Senate terms in Ohio, once a key swing state that has shifted solidly to Republicans over the past two presidential elections — with a personal appeal to working-class families and particularly union trades. Now facing a tough reelection challenge in 2024, Brown is wagering that by casting himself as a pro-labor, progressive populist, he can retain support from White working-class voters whose embrace of former president Donald Trump has propelled Ohio’s move to the right.

His race offers a key test of whether Democrats could regain support in the key state and places like it, and will be closely watched as one of a few races where Democrats must defend seats in states that Trump won, as they seek to retain their Senate majority.

“If you support workers and understand the economy depends on building out from that rather than the trickle down, the demographic or whatever change of the state doesn’t much matter,” Brown said in an interview with The Washington Post.

As Brown looks to court these voters, he faces several serious Republican challengers, who will compete to face Brown in a March primary. They include: Ohio State Sen. Matt Dolan, a former assistant attorney general for Ohio, who lost in the Republican Senate primary in 2022; Bernie Moreno, a businessman based in Cleveland who ran for the 2022 GOP Senate nomination; and Ohio Secretary of State Frank LaRose, who was a vocal proponent in the Republican-backed effort to make it harder to amend the state constitution, which would have made it harder to enshrine abortion rights in the state’s upcoming referendum.

Voters such as Joshua Kisling, a plastering business agent with the Operative Plasterers and Cement Masons International Association, who met Brown for the first time at the Dayton event, could be key to determining Brown’s ongoing appeal. Kisling said he wasn’t sure which candidate he would support in the upcoming election but walked away impressed by the longtime Ohio senator.

“He actually asked a lot of questions,” he said. “It shows he’s not just here to shake hands. He actually wants to learn a thing or two.”

After Democratic presidential candidate Barack Obama won Ohio twice by small margins, Trump swung the state back into Republicans’ hands, winning Ohio by roughly 8 percentage points in 2016 and 2020.

The political shift in Ohio came in part due to more Republican candidates, such as Trump, embracing populist messaging and appealing to voters who felt left behind by economic changes. That shift was particularly notable in counties in eastern Ohio, where voters historically supported Democrats, said Christopher Devine, an associate professor of political science at the University of Dayton.

Trump was able to bolster Republican support there, in part due to his support of the coal and fracking industries and his opposition to free-trade agreements, Devine said.

“Manufacturing areas have struggled,” Devine said. “We’ve seen significant struggles in rural areas … because of the opioid epidemic, for example. So a lot of those areas are struggling and have turned to someone who promises to change those conditions.”

Devine said Brown’s past successes have been in part due to his ability to connect with those blue-collar workers and having voters see him as “less liberal than the Democratic Party as a whole.”

“So whatever negative images, perhaps stereotypes of the Democratic Party some of these voters — who have shifted away from it — may have, to them Sherrod Brown just seems different,” Devine said in an interview.

Devine added that Brown’s support for punitive tariff measures on Chinese steel imports, backing the United States-Mexico-Canada trade agreement, which was passed under the Trump administration, and his opposition to free-trade deals have also bolstered his credibility with voters and made him stand out from other Democrats.

Despite Ohio’s political shift, Brown won his last reelection decisively. In his most recent reelection in 2018, he defeated former Republican congressman James B. Renacci by nearly 7 percentage points. After winning, Brown exclaimed that his victory showed “progressives can win, and win decisively, in the heartland.” But 2018 also followed the tradition of the political party in the White House losing heartily in the midterm elections. Democrats were widely successful running against Republicans two years into Trump’s term, taking back control of the House.

Brown told The Post that the biggest frustrations he hears from constituents are related to the economy, workers’ treatment by big companies, and layoffs at large manufacturing companies.

He said fighting for blue-collar workers will again be a central part of his campaign, leaning into the hope that his populist messaging will galvanize support from constituents.

“[Workers] still see the rich getting richer; they still see corporate interests taking advantage of them,” Brown said. “And that’s why I play on the issues I do, from banks having too much power to railroads having too much power.”

Union leaders argue Brown has delivered substantive policy wins for workers that have earned him ongoing support.

Last year, Brown played a key role in getting the CHIPS and Science Act signed into law. The legislation, championed by labor advocates, provides funds to support the domestic production of semiconductors, among other provisions. It was touted as a bill that would create thousands of jobs, including union construction jobs, and requires that the prevailing wage be used for facilities built with CHIPS funding.

Dave Green, former United Auto Workers Local 1112 president at the now-shuttered GM Plant in Lordstown, Ohio, said Brown played an instrumental part in helping workers when the company announced the Lordstown factory would close in 2019.

“Soon as the announcement was made, the senator called and said, ‘what can we do.’ It’s hard to find that in any politician,” said Green, who has known Brown for 20 years. “He’s never been afraid to take on the corporations.”

Mike Knisley, the secretary and treasurer of the Ohio State Building and Construction Trades Council, who has known the senator for more than a decade, said Brown has been vocal about advocating on unions’ behalf, particularly when it comes to new investments in the state.

“I have rarely seen people like him that actually walk the walk,” he said.

Brown’s relationship with manufacturing labor unions has allowed him to connect directly with White working-class voters. But the influence of these labor unions has shifted in recent years. Since 1990, union membership or affiliation with a union in Ohio has slowly declined from 23.2 percent of the workforce to 14 percent, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Some of the Republican candidates in the Senate primary have criticized Brown for being unable to improve the economy during his time in office.

In a statement, Dolan cited his work on economic issues in the state Senate as chair of the Finance Committee and said Brown’s record “is failing union households and working families in Ohio.”

Alex Triantafilou, the chairman of the Ohio Republican Party, believes Brown will face a tough reelection race because his voting record shows how aligned he is with the Biden administration despite his populist rhetoric.

“Ohioans have woken up to where his priorities truly are,” Triantafilou said in a statement.

Moreno and LaRose, the other Republican candidates in the Senate primary, did not respond to requests for comment on the race.

Brown is still hoping his record of working with Republicans in Congress could appeal even to voters who do not tend to support Democrats.

Brown said he has “all kinds of bipartisan accomplishments” but pointed specifically to the FEND OFF Fentanyl Act that he co-sponsored with Sen. Tim Scott (R-S.C.) as members of the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs. The bill, which has not yet been passed out of the committee, is targeted at the people who traffic fentanyl into the United States.

And in the days and months after the East Palestine train derailment in February, which led to a fire that spewed hazardous material into the air, Brown has worked with his Republican counterpart, freshman Sen. JD Vance (Ohio), on a bill that the two said would address railroad safety concerns and ensure better health-care services for constituents affected by the incident.

The senators’ bill would increase fines for safety violations and require certain procedures when trains are carrying hazardous materials. The bill passed out of committee in May but faces an uncertain future on the Senate floor.

“We have 51 Democrats supporting it. We’ve got to get 10 Republicans to break the filibuster. We’re not quite there yet,” Brown said in June at a news conference in Ohio. Republicans have expressed concerns that the bill would give the government too much control to regulate the railroad industry.

But Brown has also tried to create distance between himself and the heightened polarization on Capitol Hill. At an early March congressional hearing, Vance suggested that Biden’s administration’s slow response to the East Palestine railroad incident was in part because it was perhaps a “little too rural, maybe a little too White.”

Brown pushed back on these remarks, saying officials from both the Ohio Republican governor’s office and the White House were on the ground in the days following the derailment.

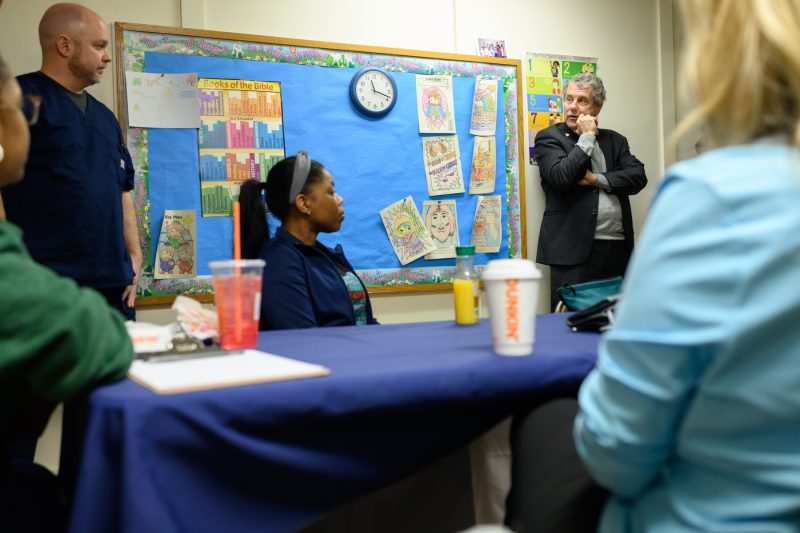

Since that hearing, Brown has gone back to East Palestine on multiple occasions to talk with medical practitioners and residents in the area. Health-care professionals have expressed concerns about an increased number of patients complaining of shortness of breath, sore throat and anxiety since the derailment.

“I think it’s important [that Brown is engaged],” said Gretchen Nickell, a doctor based in East Liverpool, Ohio, who works at a clinic Brown visited in March. “It continues to shine the light on what’s happening here so that the residents continue to get what they need.”

Tim Young, 56, a resident of Steubenville, nearly 43 miles from East Palestine, said in the first few weeks after the incident he felt nervous whenever trains passed through the city, but months later, he feels a bit better.

Young, a Democrat and Marine Corps veteran, said he will probably vote for Brown next year.

“He’s always around when something is going on. I like his attentiveness,” he said.

But five months after the train derailment, residents living near the incident still have mixed feelings about the Biden administration and Brown’s efforts to address the issue.

“The sad thing is they tried to do their best, but it’s not good enough. It’s not satisfying to the residents of East Palestine,” said Scott McAleer, who lives in East Palestine.

McAleer, a Republican who voted for Trump in 2020, said he was still experiencing symptoms months after the derailment, such as fatigue, headaches, and a bloody nose.

He added that the government could have done more. He said he’s decided not to vote for anyone in the 2024 election.