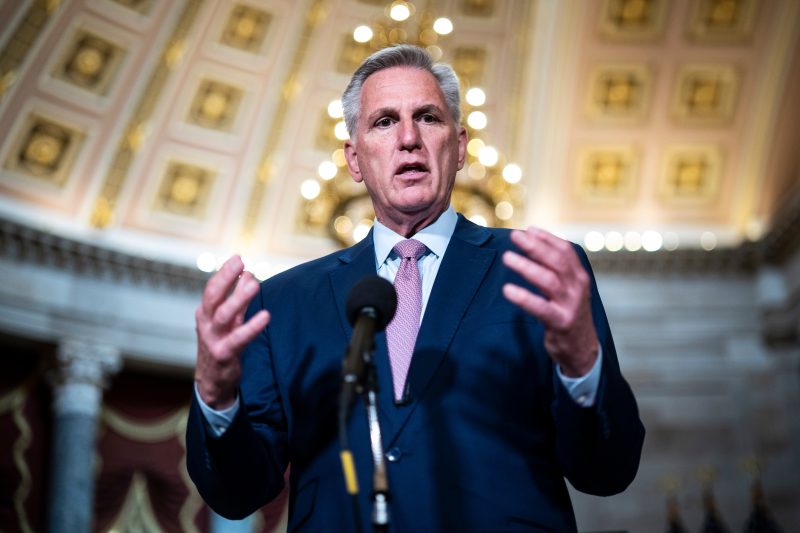

House Republicans have spent a good part of this year in a series of investigations into President Biden’s administration and family. House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) says the next “natural step” is to move toward an impeachment inquiry for President Biden. Really?

McCarthy’s justification is his assertion that the House is having difficulty getting the documents it wants for investigations that have been principally focused on Hunter Biden, the president’s son, but that Republicans are convinced implicate the president. An impeachment inquiry, he claims, would give the House the power to get the information they want.

McCarthy, who needed 15 ballots to claim the speakership, is caught between the demands of a restive Republican base looking for payback for the fact that former president Donald Trump has been indicted on 91 counts in four jurisdictions, including over efforts to overturn the 2020 election, and the reality that the public is nowhere near a judgment that such an inquiry into the sitting president is justified. If McCarthy is serious about labeling any further investigation with the word “impeachment,” it would carry considerable risk for the Republican Party.

After McCarthy made his latest comments, Ian Sams, the White House spokesman for these matters, sent out a message on X, formerly Twitter, that said, “This crazy exercise is rooted not in facts & truth but partisan shamelessness.” Still, the White House is preparing for an impeachment inquiry to begin sometime this fall.

The team geared up a year ago in anticipation that Republicans would win the House in the midterm elections and launch investigations, so an operation of lawyers, legislative experts and communications specialists has long existed. They have spent the year battling back against claims coming from congressional Republicans. Now they are prepared for what could be a significant escalation.

All of this comes as Congress returns from its August recess with the prospect of a government shutdown looming as Republican hard-liners are demanding more stringent budget cuts. This marks the second time in a matter of months that House Republicans are playing brinkmanship with the public purse.

The first came after Freedom Caucus members demanded deep cuts in spending as their price to agree to raise the government’s borrowing authority (to cover spending previously authorized). A default by the government was averted when Biden and McCarthy reached an agreement, though one that fell short of what the hard-liners had been demanding but which some lawmakers hoped would head off another confrontation this fall.

White House officials have called on lawmakers to approve a short-term measure that would give everyone more time to find an acceptable funding package by the end of the year. That would delay, but not resolve, the showdown over spending.

For some Republicans, impeachment is now directly tied to the debate over keeping the government open. Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.) told her constituents on Thursday that she would not vote to fund the government “unless we have passed an impeachment inquiry for Joe Biden.”

Impeachment used to be the tool provided by the founders to hold presidents and other officials to account for “treason, bribery or other high crimes or misdemeanors.” It was assumed that the mechanism would be used sparingly.

To date, there have been five such proceedings involving presidents.

President Andrew Johnson was the first to be impeached in 1868. He was impeached for firing a member of his Cabinet in violation of a law barring him from doing so. He was acquitted in the Senate trial by one vote.

President Richard M. Nixon was the second to face such an inquiry during the Watergate scandal. He resigned after the House Judiciary Committee approved articles of impeachment but before the full House voted. Had the process run its course, Nixon might have been convicted in a Senate trial in a bipartisan vote.

President Bill Clinton was impeached in 1998 after lying during an investigation by independent counsel Kenneth Starr into the president’s sexual encounters with Monica Lewinsky, a White House intern. Two articles were approved by the House — one for lying under oath and the other for obstruction of justice. Clinton was acquitted by the Senate on both counts. His conduct was widely judged as inexcusable, but he retained public approval in large part because the offenses were personal in nature and not official acts.

President Donald Trump set the record for presidential impeachments. The first came over his efforts to pressure Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky to dig up dirt on Biden and his son ahead of the 2020 election. Before the phone call, Trump had frozen aid to Ukraine. Trump was acquitted by the Republican-led Senate. One Republican — Sen. Mitt Romney of Utah — voted to convict.

The second impeachment came in the weeks after Trump’s followers attacked the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, after he had whipped up his loyalists with bogus claims of a stolen election. The former president currently faces two criminal indictments — one federal and the other in Georgia — resulting from his actions leading up to that attack.

Ten House Republicans joined Democrats to impeach Trump over the Jan. 6 attack and seven Republican senators voted to convict him. Even some who voted to acquit him, among them Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell (Ky.), said Trump bore principal responsibility for the Capitol attack.

Fox News had fed its viewers a steady diet of stories purporting to reveal widespread corruption in the Biden family, based largely on the misdeeds of the president’s son. Republican lawmakers have examined Hunter Biden’s foreign business dealings when his father was vice president. The president’s son is facing trial in federal court after an earlier plea deal with prosecutors collapsed. That case involves tax and firearm charges, not any foreign payments.

Hunter Biden, who has battled drug addiction, may be guilty of crimes. His upcoming trial will answer that question. He used poor judgment by profiting from the position of his father. Republicans have pointed to phone calls and two dinner meetings involving the president (then vice president), his son and his son’s business associates as questionable enough to demand more information.

Devon Archer, one of Hunter Biden’s business partners, testified before House Oversight Committee investigators that then-vice president Biden spoke with his son during business meetings about 20 times over a decade. Most were on speaker phone but in two instances, there were dinners he attended.

Archer said the elder Biden did not discuss any business dealings during those calls or meetings but also indicated there was an effort on Hunter’s part to sell “the brand.” Biden left himself open to criticism for not keeping more distance from Hunter’s business associates. Many Republicans believe there is much more to it but haven’t been able to prove it. Others in the party remain skeptical.

During the Clinton impeachment proceedings, Republicans paid a political price, losing seats in the 1998 midterm elections in defiance of history. Democrats see McCarthy’s moves as an effort to turn public attention away from the upcoming Trump trials on more serious allegations or to create a false equivalence in the minds of voters.

The speaker’s political standing remains tenuous, given the narrow majority he oversees and the rebelliousness of his hard-right fringe. Some of McCarthy’s colleagues have expressed doubts or outright opposition to moving forward with an impeachment inquiry. Rep. Ken Buck (R-Colo.) described such talk as “theater” and a “shiny object.”

McCarthy has been warned by allies, including some who believe there is enough on the public record to escalate the investigation to another level, to go slowly in the hope of turning up enough credible evidence to cause a shift in public opinion. If McCarthy lurches ahead to satisfy his base and then fails to deliver the goods against the president, the backlash could be costly to him and his party.