Nearly a century ago, nine Black teens were wrongfully accused of raping two young White women — then arrested, tried and sentenced all in the span of two weeks. Now, former president Donald Trump’s legal team has raised eyebrows by citing that case while arguing for more time to prepare a defense in his 2020 election-obstruction case.

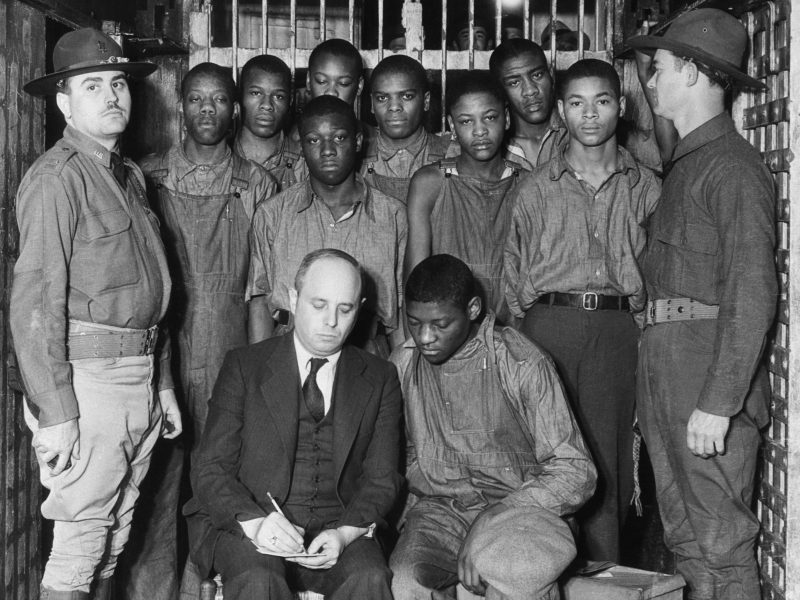

In March 1931, the teens who would become known as the “Scottsboro boys” were accused of raping the female mill workers as they passed through Alabama on a train. They were given barely any chance to talk to their attorneys before or during their brief trials by White juries, which led to death sentences for eight of them.

But the U.S. Supreme Court intervened upon appeal, saying that the accused youths hadn’t been given enough time to prepare proper defenses, and remanded the cases back to lower courts. The 1932 Supreme Court decision, Powell v. Alabama, would become a landmark ruling guaranteeing a defendant’s right to “reasonable time and opportunity to secure counsel.”

This week, that decision was cited by attorneys seeking to fight charges that Trump attempted to overturn the results of the 2020 election. The attorneys said their client needed more time to adequately prepare a defense, as guaranteed by Powell v. Alabama. U.S. District Judge Tanya S. Chutkan appeared unimpressed, denying the attorneys’ request that Trump’s trial start in 2026.

“I have seen many cases unduly delayed because a defendant lacks adequate representation or cannot properly review discovery because they are detained,” Chutkan said. “That is not the case here.” Trump has not been jailed or detained for an extensive period over his recent indictments.

Trump’s case was “profoundly different” from Powell, Chutkan added.

The Trump defense team’s decision to mention the “Scottsboro boys” was “unbelievably juvenile,” said Dehlia Umunna, a professor at Harvard Law School. “The Supreme Court held that there was an explicit denial of due process because the Scottsboro defendants were not afforded reasonable time and opportunity to procure counsel,” she said.

“That is not the case with defendant Trump. His actions leading to these charges occurred over two years ago, and he has several lawyers representing him,” Umunna said. There are no parallels between the “Scottsboro boys” case and Trump, she added.

The citation appears more aimed at Trump’s supporters “and to cast him in the position of poor black youths in the Jim Crow South who were subject to mob justice,” said Kenneth W. Mack, a professor of law and historian at Harvard University, via email.

Trump and his team have repeatedly criticized the cases against him. The former president, who is the front-runner in the 2024 Republican presidential race, is facing four separate criminal indictments: federal election-obstruction charges in D.C.; state charges of trying to obstruct the election results in Georgia; federal charges in Florida of mishandling classified documents after leaving the White House and obstructing government efforts to retrieve them; and state-level business fraud charges in New York. He and his allies have repeatedly claimed the prosecutions are politically motivated.

John Lauro, one of the attorneys for Trump, described the citation of the Powell decision as something primarily done out of duty to the court and his client, and not intended to portray the former president’s case as similar to that of the “Scottsboro boys.”

“It doesn’t mean, ‘Hey, my case is exactly like the case that I cited.’ That would be absurd. You cite a case for the legal principle it represents,” he said. “Submission to the court would have been inadequate without the citation to Powell,” he added.

Unlike Trump, who inherited millions of dollars from his father, the “Scottsboro boys” were poor African Americans who were hoboing — wandering from place to place in search of work — at the height of the Great Depression by hitchhiking on trains.

The teens, ages 13 to 19, hopped on a freight train going through Alabama on March 25, 1931. In the same car were nine young White travelers, seven male and two female. A fight erupted between them after a White youth stepped on the hand of Haywood Patterson, one of the Black youths.

In the ensuing brawl, the Black teens forced all of the White male group off the train, except one. The White youths then alerted local officials about what they described as “an assault by a gang of Blacks,” according to an account from Douglas O. Linder, a historian and an emeritus professor at the University of Missouri-Kansas City law school.

A local sheriff organized an armed group of police and civilians to confront the train in Paint Rock, Ala., where it was scheduled to stop. When the Black youths were forced off the train, the two White women, who had also been hoboing, emerged from the same car, prompting the group to ask why they were there.

The young women — Ruby Bates, 17, and Victoria Price, 21 — said they had been raped by the Black youths, who were then detained in Scottsboro, the county seat.

“The fact that they are traveling with men has already marked them as not respectable” because of the sexism of that period, said Ariela Gross, a professor of law and legal historian at the UCLA School of Law. “But when they’re discovered alone with young Black men, the pressure on them to accuse the young men of rape is very strong.”

Once the Black teens were locked up, a White mob appeared at the jail in Scottsboro, compelling the governor to deploy an 80-man National Guard detachment to protect the defendants, according to an Associated Press report from Mar. 26, 1931.

The subsequent court cases carried on for years past the teens’ initial convictions.

The trials reflected the racism prevalent in the South, where all-White juries continued to see the “Scottsboro boys” as guilty of rape, even as evidence indicating their innocence emerged.

In early 1932, a letter from Bates to her boyfriend surfaced in which she denied having been raped. In subsequent court testimonies, Bates again denied any rape had occurred. In public, she told a mostly Black crowd that the “Scottsboro boys” were innocent, The Washington Post reported in May 1933. Price, who died in 1982, never rescinded her accusations.

Court testimony from a doctor who had performed an examination a few hours after the alleged rape, which suggested that there were few signs of rape, was ignored.

It would take eight more decades and multiple appeals, hearings and pardon pleas to reverse the false Jim Crow-era convictions. In 2013, the last three “Scottsboro boys” who had not yet had their convictions dropped or overturned were posthumously pardoned. They collectively served more than 100 years in prison.

“The Scottsboro decision is one of the landmarks of American law,” said Mack, the Harvard law professor. “It is hard to believe that Trump’s legal team actually thought that citing it would be persuasive for this judge, or for any subsequent judges who will rule on appeals after the trial is over.”

But Trump’s attorneys probably want to buttress his “claim to his supporters that he is being persecuted,” Mack added in an email. “Although of course to be persuaded one has to believe the fantasy that the former president of the United States is like a poor black defendant in the Jim Crow South.”