Record numbers of migrant families streamed across the U.S.-Mexico border in August, according to preliminary data obtained by The Washington Post, an influx that has upended Biden administration efforts to discourage parents from entering illegally with children and could once again place immigration in the spotlight during the 2024 presidential race.

The U.S. Border Patrol arrested at least 91,000 migrants who crossed as part of a family group in August, exceeding the prior one-month record of 84,486 set in May 2019, during the Trump administration. Families were the single largest demographic group crossing the border in August, surpassing single adults for the first time since Biden took office.

Overall, the data show, border apprehensions have risen more than 30 percent for two consecutive months, after falling sharply in May and June as the Biden administration rolled out new restrictions and entry opportunities. The Border Patrol made more than 177,000 arrests along the Mexico border in August, up from 132,652 in July and 99,539 in June.

Erin Heeter, a spokesperson for the Department of Homeland Security, said the Biden administration is trying to slow illegal entries by expanding lawful options and also stiffening penalties. The government ramped up deportation flights carrying families in August, she said, and since May has repatriated more than 17,000 parents and children who recently crossed the border in family groups.

“But as with every year, the U.S. is seeing ebbs and flows of migrants arriving fueled by seasonal trends and the efforts of smugglers to use disinformation to prey on vulnerable migrants and encourage migration,” Heeter said in a statement.

Family groups have been an Achilles’ heel for U.S. immigration enforcement for over a decade. Most migrants in that category who are detained by Border Patrol agents are quickly released and allowed to live and work in the United States while their humanitarian claims are pending. Backlogged U.S. immigration courts typically take several years to reach a decision, and the process rarely ends in deportation, federal data show.

Coming amid peak summer heat, the latest surge underscores the extent to which U.S. immigration enforcement has come full circle since Trump’s tenure, when the Department of Homeland Security faced an influx of families crossing over from Mexico and for several months tried taking children from their parents as a deterrent.

Trump officials eventually reduced family crossings by aggressively expanding the “Remain in Mexico” program, which sent thousands of asylum seekers back across the border to wait, many in squalid conditions, while their claims were adjudicated in U.S. courts.

When the pandemic hit in early 2020, Trump used a provision of Title 42, the U.S. public health code, to rapidly expel border-crossers to their home countries or Mexico without a chance to seek asylum. U.S. Customs and Border Protection carried out 3 million expulsions, including families between March 2020 and May 2023, records show.

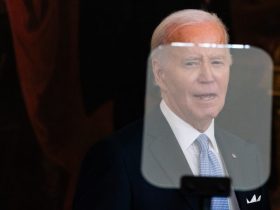

President Biden, who ran for office pledging more humane treatment for migrants, halted Remain in Mexico and closed the three detention centers for families operated by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Biden has replaced the pandemic policy with new measures that allow tens of thousands more migrants to come to the United States legally each month but make it harder for those who cross illegally to get released after making an asylum claim.

The latest Customs and Border Protection data show more than 50,000 migrants were processed in August at U.S. border crossings, where the Biden administration is allowing up to 1,450 per day to schedule an appointment to enter the country lawfully using a mobile app. That increased the total number of migrants encountered by CBP at the southern border in August — at legal crossings or elsewhere — to about 230,000, the highest one-month total this calendar year.

A separate Biden program accepts roughly 30,000 applicants per month from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua and Venezuela who obtain authorization to live and work in the United States for two years if they have a financial sponsor and clear background checks. The program, known as parole, allows beneficiaries to fly to the United States instead of crossing at the border.

Both programs are facing challenges in federal court from officials in Republican-led states.

Illegal crossings by migrants from the parole-eligible countries have fallen sharply. But CBP records show major increases this summer in migration from Guatemala, Honduras, Ecuador, Peru and an array of nations in Asia and Africa. The arrival of thousands of parents with children in remote areas amid triple-digit temperatures is a major humanitarian, linguistic and logistical challenge.

The Biden administration has expanded the border agency’s network of climate-controlled “soft-sided” tent facilities with medical staff and social workers on hand to help care for children. But many families still first encounter traditional CBP stations, which have windowless, grim detention cells with concrete benches and were designed as short-term holding facilities for adults.

Blas Nuñez-Neto, the Biden administration’s top border policy official, said in a federal court filing last week that bipartisan efforts to control the border helped reduce illegal crossings from more than 1 million a year decades ago to fewer than 400,000 a year, on average, from 2011 to 2017.

But partisan gridlock has intensified — and the demographic makeup of migrants has changed. Officials saw a marked increase in families and unaccompanied minors arriving at the southern border. Some have been targeted by violence in their home countries that could make them eligible for humanitarian programs. But others are relying on promises from smugglers, who tell them families are far less likely to be deported.

The August tally brings the total number of “family member units” surrendering at the southern border during the current fiscal year to more than half a million people, a record high, with one more month to count.

The Biden administration has sent mixed messages about targeting families for deportation.

During his first year in office, Biden pledged to reunite the families Trump had separated and to protect undocumented families already living inside the United States. In 2021, Biden administration officials ended family immigration detention and declared schools and “places where children gather” off-limits for immigration enforcement. Officials said they would not detain or deport women who ae pregnant or breast feeding.

But officials said they would continue to deport families who had recently crossed the border, worried that if they didn’t, their numbers would overwhelm Border Patrol facilities. In recent months, Biden administration officials have held news conferences with Spanish-language media and published footage of deportation flights carrying children to discourage families from attempting to cross.

The Biden administration also has created enforcement programs targeting families: In 2021, Department of Homeland Security and Justice Department officials created a “dedicated” immigration court docket in 11 cities to adjudicate family cases within 300 days of the initial hearing. The expedited system, which is not for all families, is much faster than the usual time for the backlogged immigration courts.

The program operates in Boston, Denver, Detroit, El Paso, Los Angeles, Miami, Newark, New York, San Diego, San Francisco and Seattle. Advocates for immigrants say the system is unfair because thousands of migrants have been unable to find lawyers and it is unclear how families are assigned to the faster docket.

In May, Biden officials launched the Family Expedited Removal Management program, or FERM, which places some heads of households under GPS monitoring and into the fast-track deportation process. These families also have mandatory curfews from 11 p.m. to 5 a.m. CBS News reported Thursday that fewer than 100 family members have been deported from that program.

“FERM is one element of DHS’s operations to enforce U.S. immigration law and to remove individuals and families without a legal basis to stay in the country,” DHS’s Heeter said.

DHS has removed or returned more than 200,000 recently arrived migrants since May, Heeter said, a number that includes the 17,000 who came to the United States as part of a family group.

In fiscal year 2019, Immigration and Customs Enforcement deported more than 5,700 people who had entered the United States as part of a family group, more than double the number from the year before, according to a federal report.

Official family deportations spiked to nearly 14,500 in 2020 and then sank during the pandemic, when the government’s usual policies were replaced by quick expulsions under Title 42 that did not carry the same legal penalties as a deportation.