Rep. Steve Womack (R-Ark.) was jolted out of the often-mundane work of presiding over the House when liberal activists in the public gallery started shouting and protesting. Just a few months into office, he didn’t know what to do.

“The chair has observed a disturbance,” Womack recalled saying, delivering a brief speech while banging the gavel to bring the chamber back to order. Once things settled down, the parliamentarian’s staff found the formal script for such moments — Womack had, on instinct, delivered the almost perfect response.

A gavel-wielding star was born. By the last day of his first term — a contentious New Year’s Day session in 2013, with Womack presiding again — he had logged more hours in the chair than any member of the huge freshman class. He instantly loved what many saw as a cumbersome task with little reward, and now, after four years in the minority, Womack is once again the go-to officer to preside over tense debates in the House.

“I came in as an institution guy,” Womack, a former mayor and 30-year member of the Army National Guard, said during an hour-long interview. He won’t even allow the slightest misstep of words when a member rises to speak until that member properly asks for “unanimous consent.”

“I want people to have enough respect for the institution that they adhere to the institutional norms, and when things go haywire, and they often do, it breaks my heart,” he added.

That is why these next 45 or so days will be the longest late-summer recess of his 13 years in Congress. Rising in power and respected on both sides of the aisle, Womack, 66, has grown so fed up with his party’s leadership kowtowing to a small band of hard-right lawmakers that he is considering retiring next year.

Expecting to make a decision around Labor Day, he will weigh whether Republican dysfunction is “so unpleasant” that he can no longer “be a difference maker” in the chamber he loves.

“Then I’ll go do something else,” he said.

After this column appeared online Saturday, Womack tweeted a statement stating as of now he intends to run again: “To be clear, I am frustrated with the state of play in Congress; however I have every intention of running for reelection and using my work to fix the institution I love,” he wrote.

He recounted leaving his longtime Methodist church during a late-1990s mayoral race because fellow congregants attacked him in the local press.

“Life is too short to sit in misery,” Womack said.

His friends are giving him space to make the decision but worry that his retirement would lead to his conservative northwestern Arkansas district replacing him with a more fire-breathing Republican. And some fear that Womack’s would not be the only retirement from the workhorse wing of the House GOP.

“He’s one of the brightest guys here in Congress. And he loves the institution and is frustrated, like I and others are, about what’s happening to it,” said Rep. Mike Simpson (R-Idaho), who is in his 25th year in Congress and has been a mentor to Womack. “I think there’s a lot of people like that, to tell you the truth. It’s just people considering: Is this really worth it?”

Simpson gave an equivocal answer about his own reelection bid in 2024. “Right now, I’m running again,” he said, pausing for effect. “Right now.”

That Womack has ended up so frustrated is an indictment of the state of congressional politics. He arrived 12 ½ years ago fairly awestruck.

While serving in the Guard, he won his first campaign, in 1996, for mayor in Rogers, Ark., a few miles east of the then-burgeoning city of Bentonville. The thousands of outsiders who’ve moved to the region to work at Walmart have softened the edge of a congressional district that has been in Republican hands for more than 55 years — Donald Trump’s 60 percent support there in 2016 and 2020 fell well below Mitt Romney’s 66 percent of the vote in 2012.

So after winning the 2010 House race, Womack immediately sought out a path toward traditional, insider influence. He bumped into Rep. Harold Rogers (R-Ky.), the incoming chairman of the Appropriations Committee, during orientation and gave a brief pitch about why Rogers should put him on the committee, citing all his prior work.

“You might be interested in knowing the name of the city where I was mayor,” Womack recalled saying, growing a bit desperate. “Rogers, Arkansas.”

“You’re exactly what I’m looking for,” Rogers replied, poking him in the chest.

Two years later, after that chaotic New Year’s Day conclusion to the term, House Speaker John A. Boehner (R-Ohio) apologized for how Womack got stuck presiding as Democrats protested the delay of emergency funding after Superstorm Sandy. Womack politely asked to get a spot on the defense subcommittee, a plum gig funding the Pentagon, and Boehner said yes.

By the summer of 2016, Speaker Paul D. Ryan (R-Wis.) appointed Womack to preside over that summer’s contentious rules fights during the Republican National Convention, and by 2018, Womack became the chairman of the House Budget Committee.

He was a joyful soul, sitting down in the front row of the chamber happily trading stories with veterans like Rogers, Simpson and others. He even served on the secretive-but-influential steering committee, deciding which lawmakers were assigned to which committees and who served as chairs.

While others sought cable news and social media highs, Womack stuck to his committee work, focusing on his district, and, so far anyway, he has not faced a credible primary challenge from his right while winning every general election by at least 2 to 1.

Then Republicans lost the 2018 midterms, and Ryan, like Boehner before him, retired. Rep. Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.), now the speaker, became minority leader and, slowly but surely, the House GOP’s center of gravity started drifting away from people like Womack.

Rep. Jim Jordan (R-Ohio), one of McCarthy’s biggest antagonists from the right, became McCarthy’s confidant. And McCarthy leaned in heavily to President Donald Trump as the 2020 election approached, and whenever some Republican acted up, very few faced any real punishment.

Womack’s turning point came Jan. 6, 2021, when then-Rep. Mo Brooks (R-Ala.) spoke at the Trump rally that preceded the joint session of Congress held to certify Joe Biden’s presidential election victory. Brooks called for “taking down names” of Republicans who didn’t back Trump’s false claim of victory.

When the dust settled after the ensuing riot, Womack voted with one-third of his conference to certify Biden’s win. He then sought to punish Brooks for his pointed attacks on fellow Republicans by using his steering committee perch to try to remove Brooks from the Armed Services Committee.

“I think I had the votes,” Womack said. McCarthy and leaders delayed that vote and eventually tipped the scales for Brooks.

“Keeping him on Armed Services was rewarding him for comments that were just completely out of line,” Womack said during the interview, explaining how he quit the steering committee in protest. “And I felt so principled about it that I just didn’t want to be associated with an organization that was going to be populating committees with people like that.”

The joy of winning back the majority last November, giving him a subcommittee chairman’s gavel overseeing roughly $30 billion of federal funds, began to fade when McCarthy had to go 15 rounds of balloting to secure the votes to become speaker. A series of closed-door sessions between McCarthy and far-right lawmakers led them to proclaim that they had secured secret promises from McCarthy.

“That’s not how you want to govern as speaker, where there is a feeling out there that you cut a deal with some other people and we don’t really know what the deal is,” Womack said.

Contrasting McCarthy with Boehner, Womack said some members have trouble taking the speaker at his word.

“I want him to mean what he says and stand by his position among a conference that sometimes can get sideways with him. That’s kind of the military in me,” the former Army colonel said. In defending his soft touch as House speaker where discipline is concerned, McCarthy has said that he prefers to reprimand wayward Republicans in private discussions rather than with public admonishment or actual punishments.

In the late spring, after McCarthy and Biden clinched a budget framework deal, the far-right flank objected to those spending levels and the Appropriations Committee was told to drop more than $100 billion from its dozen bills. Womack’s bill cut funding for agencies such as the IRS and the Securities and Exchange Commission by billions of dollars while also adding policy riders that restrict D.C. traffic cameras, and other culture-war items.

Democrats generally respect Womack and accuse McCarthy of caving to the ideologues, but Womack does vote for these bills.

“Awful things are put in bills,” said Rep. Steny H. Hoyer (Md.), the top Democrat on Womack’s subcommittee. “And people who don’t believe in awful things are voting for the bills.”

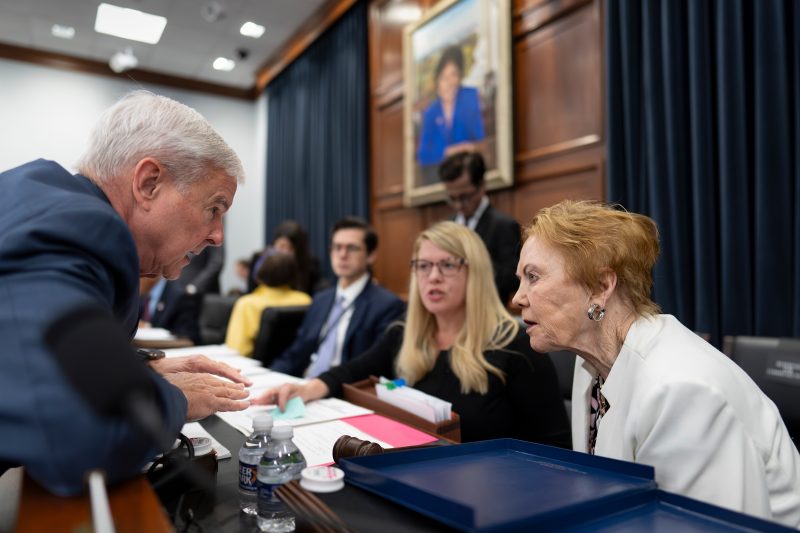

Early this year, during the first major slog of amendments, Womack took over as presiding officer and explained that the nearly two dozen votes would be completed in 2-minute increments.

“Two minutes is two minutes,” he said, eliciting cheers from both sides of the aisle. He felt good about his standing in the institution.

Now he’s going to spend the next few weeks deciding whether the institution itself is fixable, with him or without him.

“We can’t afford to lose people like him,” Simpson said.