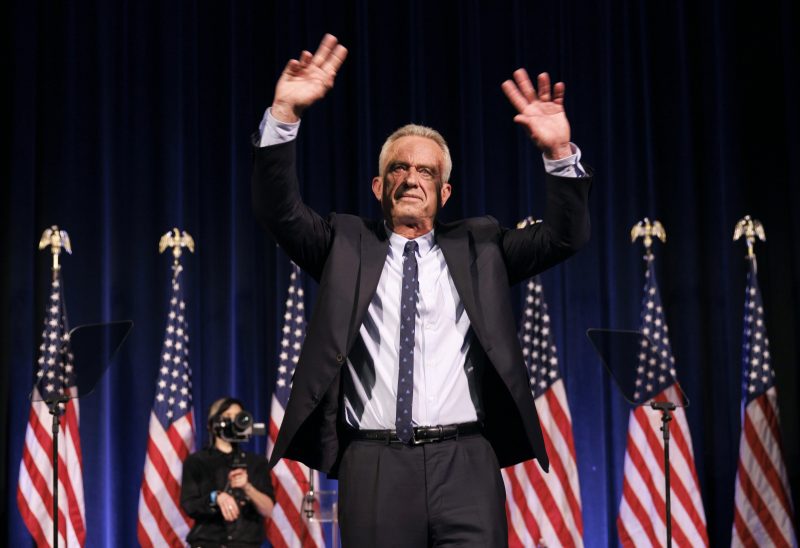

For understandable reasons, the tidbit of Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s comments about genetically engineered “microbes” that captured the public imagination over the past week were the ones centered on Jewish people.

The coronavirus that causes covid-19, he said at a dinner attended by the New York Post, was “targeted to attack Caucasians and Black people” while it offered protection to “Ashkenazi Jews and Chinese.” At other times he tried to qualify this — there’s “an argument that [the virus] is ethnically targeted,” he said a bit earlier — but the intent of his comments, rooted in the expertise of “doing a book on it for the past two and a half years,” is obvious.

In fact, extending outward from the comment about Jewish people, Kennedy’s falsehoods only become more laden with outlandishness. Those types of falsehoods often find their way into part of conspiracy theories, which often are a bundle of red yarn tying in nearly everything.

First of all, just on this point, he’s wrong. Study after study after study has shown that Jewish people (most of whom are Ashkenazi) were actually disproportionately harmed by covid-19 across multiple countries. The idea that Chinese people were protected from the virus, according to Kennedy’s remarks, means either accepting the country’s obviously artificial toll as accurate or ignoring a lot about the pandemic.

But, again, this was a subset of what Kennedy said at the dinner. He also claimed, for example, that the United States had “put hundreds of millions of dollars into ethnically targeted microbes,” which is what “those labs in the Ukraine are about: they’re collecting Russian DNA. They’re collecting Chinese DNA so we can target people by race,” he said, according to the New York Post.

We can start here by pointing out that it would be far more useful to try to collect “Chinese DNA” in the United States than in Ukraine, should one wish to do so. But the entire concept here is dubious, rooted in obviously fraught assertions about fundamental genetic differences between nebulously bounded groups. The American Medical Association has publicly rejected the idea while noting that such claims are an essential component of racism. Whatever one’s opinion of the AMA, it is indisputable that it has more cumulative expertise and research hours on medical issues than does Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

Close observers of the political conversation in recent years will have noticed Kennedy’s invocation of “labs in Ukraine” as significant. When the full-scale Russian invasion began last year, the idea that the Russians were seeking in part to dismantle U.S. biolabs in Ukraine became a common bit of rhetoric on the political right. Tucker Carlson, then perched in the Fox News prime time lineup, offered this idea as a rationalization for the invasion — and as a way to pin blame for the invasion back on the U.S. government. Kennedy, dizzily stabbing pushpins into his corkboard, wrapped this into his broader just-asking-questions about the coronavirus.

Kennedy’s attempt to repurpose fringe-right conspiracy theories is hardly new for his candidacy. In many ways, Kennedy is doing what Donald Trump did with the Republican Party in 2015, offering a conspiratorial right-wing worldview to primary voters.

Kennedy’s challenge, relative to Trump, is that there is less appetite for such ramblings on the left. In part, this is because fewer Democrats are immersed in a media universe in which conspiracy theories are the watchword. Kennedy didn’t launch his campaign on the back of years of rhetoric from increasingly popular fringe media outlets in the way that Donald Trump did.

In fact, since he launched his campaign, Kennedy’s political position has improved — but only among Republicans.

Kennedy has decent favorability ratings relative to other candidates, but that’s largely because he’s viewed much more positively among Republicans who otherwise give Democrats low rankings. Again, this is in large part a function of Kennedy’s rhetoric finding a receptive audience with right-wing media outlets.

After the New York Post’s report on Kennedy’s comments, the Democratic Party was quick to distance itself from a guy who is seeking the party’s presidential nomination.

“These are deeply troubling comments and I want to make clear that they do not represent the views of the Democratic Party,” party chairman Jaime Harrison wrote on Twitter.

The Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee offered an even more aggressive response. Kennedy’s comments included “reprehensible anti-semitic and anti-Asian comments aimed at perpetuating harmful and debunked racist tropes,” it said in a statement. “Such dangerous racism and hate have no place in America, demonstrate him to be unfit for public office, and must be condemned in the strongest possible terms.”

It’s not surprising that the party’s institutions and leaders would take this tack; the Democratic Party is keenly attuned to racist stereotypes and antisemitism. But it is also not much of a burden. Kennedy’s support in the primary is not particularly robust relative to the incumbent president, and his long-standing conspiratorial rhetoric has not been effective at building a constituency. The party is certainly eager that it doesn’t.

Compare the response here with the Republican Party’s response to Donald Trump in 2015. The chairman of the party then, Reince Priebus, didn’t excoriate Trump’s repeated rhetoric about criminal immigrants on social media. The party doesn’t appear to have done so either, though it did offer a condemnation of his later disparagement of the military service of Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.). (That came from Sean Spicer, who would later accept a gig as Trump’s White House press secretary.) For the GOP, Trump’s controversial comments were already accepted by a large segment of its base, which is why his candidacy quickly gained traction.

There is an interesting question inherent to the Kennedy situation for the Democratic Party: How accountable is it for the espoused views of one of its candidates for the presidential nomination? What is it about Kennedy that demands a response at all? Is it his name? Because he’s getting more than zero percent in polls? Is it simply that Kennedy affords Democrats an opportunity to reinforce who they are relative to what he presents?

Or is it also that the party has seen what happens if you don’t challenge the fringe assertions of a long-shot celebrity candidate for the presidency?