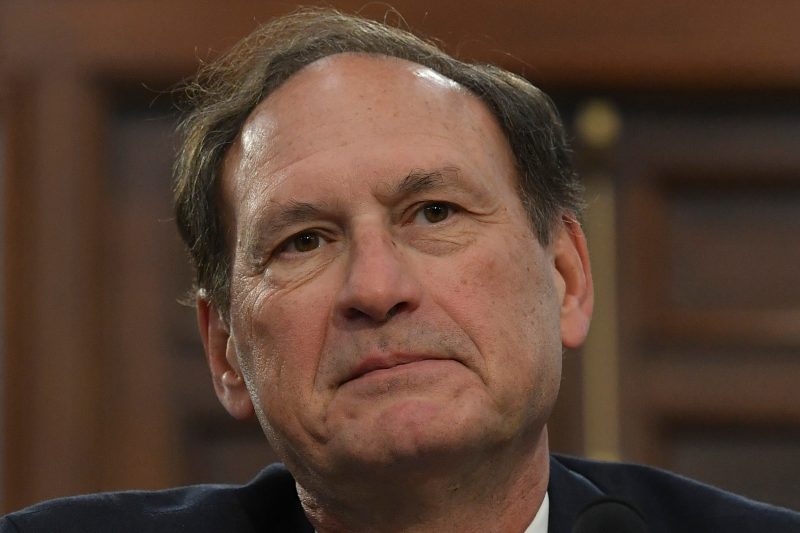

Scrutiny of the Supreme Court intensified Wednesday after Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. took the extraordinary step of writing an op-ed column to defend a luxury fishing trip to Alaska years ago that was partially financed by a politically active billionaire. Senate Democrats said the revelation of the trip, by the news organization ProPublica, was one more reason they would move forward on legislation to tighten ethics rules for the justices.

Although there appears to be little interest in the Republican-led House in forcing changes upon the high court, Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Richard J. Durbin (D-Ill.) said his panel would consider legislation after the Senate returns from its Fourth of July recess.

“The highest court in the land should not have the lowest ethical standards. But for too long that has been the case with the United States Supreme Court. That needs to change,” Durbin said in a joint statement with Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.), who chairs a subcommittee with jurisdiction over the federal judiciary.

Whitehouse has pushed legislation that would require the court to adopt a code of conduct and establish clear rules dictating when justices must recuse themselves from cases. A separate bipartisan bill by Sens. Angus King (I-Maine), who caucuses with the Democrats, and Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) would force the Supreme Court to establish an ethics code and require it to appoint an official to examine potential conflicts and public complaints. Legislation introduced by Sen. Chris Murphy (D-Conn.) would require the Judicial Conference of the United States, the policymaking body for the federal courts, to issue an ethics code that would apply to the court.

It was not immediately clear which provisions might be considered in July.

The statement by Durbin and Whitehouse took direct aim at Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., saying that the Supreme Court is in the midst of “an ethical crisis of its own making” and that Roberts “could resolve this today, but he has not acted.”

ProPublica reported late Tuesday that in July 2008, hedge fund manager Paul Singer flew Alito to King Salmon Lodge, a fishing resort in a remote corner of Alaska that charged more than $1,000 a day. If the justice chartered the plane himself, the cost could have exceeded $100,000 each way, the publication reported.

Alito struck back in a column on the Wall Street Journal editorial page even before the ProPublica piece was published. The column was headlined “ProPublica Misleads Its Readers” and included Alito’s rebuttals to questions posed by the ProPublica reporters — answers the justice did not share with the reporters before publication. In the op-ed, Alito said he was neither required to report the fishing trip on his annual disclosure form nor to recuse himself from cases before the court that involved Singer.

“It was and is my judgment that these facts would not cause a reasonable and unbiased person to doubt my ability to decide the matters in question impartially,” Alito wrote.

It is exceedingly rare for a justice to write an op-ed, especially one defending his own actions. A court spokesperson said Alito had no additional comment Wednesday.

Conservative activist Leonard Leo attended and helped organize the fishing trip, while conservative donor Robin Arkley II, who owned the lodge, hosted the justice as his guest, according to ProPublica. In the subsequent years, Singer’s hedge fund came before the court at least 10 times in cases where his role was often covered by the mainstream media and the legal press, ProPublica reported.

Alito wrote in the op-ed that he wasn’t aware that Singer was connected to the cases when the cases went before the court. He recalled speaking with him on “no more than a handful of occasions” and wrote that they never “talked about any case or issue before the Court.”

Alito also said his seat on Singer’s plane “would have otherwise been vacant” and argued that, at the time, justices did not generally think they were required to disclose the provision of “accommodations and transportation for social events.”

ProPublica said another guest on the trip was Judge A. Raymond Randolph. Randolph told the publication he also traveled on a June 2005 trip to Alaska that included then-Justice Antonin Scalia. After that trip, Randolph said, he contacted the federal judiciary’s financial disclosure office to ask whether it needed to be disclosed. He said he was told no, an answer ProPublica said was documented in Randolph’s notes about the call.

The explanations were similar to a defense offered by Justice Clarence Thomas following a ProPublica report earlier this year that said he accepted luxury trips around the globe for more than two decades, including travel on a superyacht and private jet, from Harlan Crow, a prominent Republican donor, without disclosing them. Thomas said he was advised “by colleagues and others in the judiciary” that he did not need to report those gifts.

Thomas also has drawn scrutiny on other fronts, including having Crow pay private boarding school tuition for his grandnephew, a young man the justice has said he raised as a son, as well as Crow’s purchase of three properties in Savannah, Ga., from Thomas in 2014, including the house where Thomas’s mother was living.

Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.), a member of the Judiciary Committee, said he would like to see the Senate act within weeks “to hold the court accountable to adopt a code of ethics.”

“That’s what I’m pushing to do,” he said. “I think we need to use whatever means necessary.”

Federal ethics law requires top officials from all three branches of government, including Supreme Court justices, to file annual financial disclosure forms listing outside income, gifts and investments. A separate judicial conduct statute allows for the filing and investigation of misconduct complaints against lower-court judges.

The Supreme Court does not have such a process for misconduct complaints or a binding ethics policy. The justices have discussed but have not reached a consensus on a policy, The Post reported this year, despite talks dating from at least 2019.

Judges are prohibited from accepting gifts from anyone with business before the court. Until recently, however, the judicial branch had not clearly defined an exemption for gifts considered “personal hospitality.”

Many legal experts have argued an ethics code tailored to the high court is long overdue.

“The public’s trust in the court is essential,” said James J. Sample, a law professor at Hofstra University. “The essentiality of that trust does not square with lavish, undisclosed luxuriating via the largesse of private benefactors, and particularly not when those benefactors not only have direct interests before the court, but also have derivative interests in connecting their friends to their beneficiaries on the bench.”

Louis J. Virelli III, a professor at Stetson University College of Law and an expert on judicial recusals, said he believes that Alito should have disclosed the trip and that, if justices are going to accept gifts from high-profile figures such as Singer, they need to be especially careful about possible conflicts. In such instances, “the justices have an even greater responsibility to do their due diligence about who’s appearing or having an interest,” he said.

Supreme Court 2023 decisions

End of carousel

This spring, a committee of the Judicial Conference, the courts’ policymaking body, revised disclosure rules to be more specific — spelling out, among other things, that judges must report travel by private jet. Gifts such as an overnight stay at a personal vacation home owned by a friend remain exempt from reporting requirements. But the revised rules require disclosure when judges are treated to stays at commercial properties, such as hotels, ski resorts or other private retreats owned by a company, rather than an individual.

The Rev. William R. Dailey, a lecturer in law at Notre Dame Law School, said the changes lend credence to the claims of Thomas and Alito that such “personal hospitality” did not previously need to be reported. Dailey also noted the reluctance of justices to recuse themselves from cases because there is no one who can replace them on a case, unlike in lower courts.

But he said lavish trips create a problem for the judiciary’s appearance. “On a macro level,” he said, ordinary Americans think justices, and other public officials, “shouldn’t be jumping on billionaire’s junkets.” If the Judicial Conference does not simply prohibit such trips, he said, it could require some sort of compensation from the justices or perhaps limit the givers of such gifts to family members and longtime friends, people whom judges and justices knew before they were on the bench.

The rules change applies to disclosure forms filed this year for 2022. Both Thomas and Alito requested extensions for those forms, so their disclosures are not yet public.

While Democrats have grown increasingly frustrated with the justices, Republicans have argued the push to impose an ethics code is aimed at undermining the legitimacy of a conservative-leaning court.

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) told reporters Wednesday that he doesn’t think Congress has the “jurisdiction” to tell the Supreme Court how to handle ethics issues.

“Look, the Supreme Court, in my view, can’t be dictated to by Congress,” he said. “I think the chief justice will address these issues. Congress should stay out of it.”

The chief justice has resisted previous congressional efforts to impose changes, but he also recently acknowledged the controversy.

“I want to assure people that I’m committed to making certain that we as a court adhere to the highest standards of conduct. We are continuing to look at things we can do to give practical effect to that commitment,” Roberts said when accepting an award last month from the American Law Institute. “And I am confident that there are ways to do that consistent with our status as an independent branch of government and the Constitution’s separation of powers.”

Ethics issues have been raised regarding other justices as well.

In May, a conservative news site, the Daily Wire, questioned Justice Sonia Sotomayor’s decision not to recuse herself from two Supreme Court cases involving Penguin Random House, which publishes her books and has paid the justice about $3.6 million since 2009 — income she listed on her disclosure forms.

Justice Neil M. Gorsuch has faced questions involving the same publisher. He has received $655,000 from the company, according to his financial disclosure reports, and he also did not recuse himself in a case that came before the court during his tenure.

Since Scalia’s death in 2016, Alito has emerged as the justice most eager to take on critics, with rock-ribbed speeches and caustic opinions.

In 2020, he drew sharp criticism for a speech to the Federalist Society that Democrats said read like a political speech, rather than a judicial address.

He recited “previously unimaginable” pandemic-related restrictions on individual freedoms and lamented that freedom of speech, religion and gun rights are in danger of “second-tier” constitutional status.

He again raised his disagreements with the court’s recognition of same-sex marriage.

These days, “you can’t say that marriage is a union between one man and one woman” without fear of reprisal from schools, government and employers, Alito said.

“Until very recently, that’s what the vast majority of Americans thought. Now it’s considered bigotry,” he said, adding: “One of the great challenges for the Supreme Court going forward will be to protect freedom of speech.”

After penning the court’s landmark Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision striking down federal abortion rights last year, Alito spoke to the Notre Dame Religious Liberty Summit, sponsored by the Religious Liberty Initiative at the university’s law school, mockingly dismissing criticism of the ruling from overseas.

“I had the honor this term of writing I think the only Supreme Court decision in the history of that institution that has been lambasted by a whole string of foreign leaders who felt perfectly fine commenting on American law,” Alito said.

The justice had also made another recent appearance on the Wall Street Journal editorial page.

In an interview published in April, Alito declined to answer questions about Thomas and reports about his travels. But Alito said he believed that reports about alleged ethical violations by justices are attempts to damage the court’s credibility now that conservatives are firmly in control. “We are being hammered daily, and I think quite unfairly in a lot of instances. And nobody, practically nobody, is defending us,” he said.

“And then those who are attacking us say, ‘Look how unpopular they are. Look how low their approval rating has sunk,’” Alito said. “Well, yeah, what do you expect when you’re — day in and day out, ‘They’re illegitimate. They’re engaging in all sorts of unethical conduct. They’re doing this, they’re doing that’?”

Camila DeChalus contributed to this report.