On Jan. 2, 2021, Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Tex.) announced a plan to block the recognition of electors from states that voted for Joe Biden in the previous year’s presidential election. In a statement signed by nearly a dozen sitting senators and senators-elect, Cruz called for the formation of a commission to “conduct an emergency 10-day audit of the election returns in the disputed states” — that is, states that flipped to Biden after Donald Trump won them in 2016.

This was necessary, the statement read, because the election “featured unprecedented allegations of voter fraud, violations and lax enforcement of election law, and other voting irregularities.”

Did you catch that? Not because there was unprecedented fraud or violations but because of allegations of the same. That’s what made those states “disputed”: Trump was stoking unfounded claims about fraud in an effort to retain power. So Cruz et al., interested in leveraging Trump’s falsehoods to boost their own positions, cited the allegations themselves as demanding redress. Instead of standing athwart Trump and pointing out that the allegations had no basis in fact, they agreed with the crowd that the emperor was the best-dressed guy in Washington.

Theoretically, leadership includes challenging those being led to be better. But, as any parent of a petulant child can attest, sometimes it’s easier just to let them do their thing.

Until this weekend, Cruz’s statement was the best example of how Trump’s grip on the most vocal portion of the Republican base spurs his allies to explicitly kowtow to baseless beliefs. During an appearance on ABC News’s “This Week,” though, Sen. Lindsey O. Graham (R-S.C.) offered another good one.

Host George Stephanopoulos asked Graham whether he believed Trump’s assertions that he did nothing wrong in the chain of events that led to his indictment last week on federal charges. Graham quickly transitioned to “whataboutism.”

“Most Republicans believe we live in a country where Hillary Clinton did very similar things and nothing happened to her,” Graham told Stephanopoulos. “ … Did he do things wrong? Yes, he may have. He will be tried about that. But Hillary Clinton wasn’t.”

It’s true that Clinton was not put on trial. And Graham, as a U.S. senator now and at the time that the questions about Clinton were under consideration, should understand the distinction.

As I wrote last week, the FBI announced in summer 2016 that it would not be charging Clinton for having classified material on her private email server because indictments generally involved “clearly intentional and willful mishandling” of such material or “efforts to obstruct justice,” among other things. What Trump is alleged to have done ticks both of those check marks: He is accused of having willfully retained documents that were improperly stored and of blocking the government’s efforts to recover them.

But Graham isn’t arguing that Clinton did what Trump did. He’s arguing that most Republicans think Clinton did what Trump did. And on that basis, he’s defending Trump.

Let’s assume, even in the absence of poll data to support it, that Graham’s assertion is true, and that most Republicans do think that. Why do they think it? Centrally because Trump and his allies have spent years suggesting that Clinton skated because of politics and months suggesting that the two scenarios are fundamentally comparable. In other words, a central reason this belief is widely held is that Trump himself espouses it.

The chain of logic, then, goes like this: Trump presents argument, his base accepts argument, Graham points to that acceptance as defense of Trump. See the problem? It’s the same self-reinforcing chain that undergirded Cruz’s comments about the 2020 election.

“We live in a world today where most Republicans believe that Hunter Biden’s laptop was real and people knew it was real but they told the public something else to help Joe Biden,” Graham also told Stephanopoulos. “ … I know you don’t get what I’m saying, but people on my side believe it, and I think Donald Trump is stronger today politically than he was before.”

Here we have a refreshingly blunt connection between the belief and Trump’s political strength. The vagueness of Graham’s presentation — what is the junction of “people knew” and “they told” here? — is used to elevate the idea that the Republican position demands redress. And without that redress, unattainable because it is rooted in false assumptions about knowledge and intent, Trump grows ever stronger.

On Jan. 6, 2021, Cruz gave a speech on the floor of the Senate arguing against recognition of the electors submitted by the state of Arizona.

“Recent polling shows that 39 percent of Americans believe the election that just occurred, quote, was rigged,” Cruz said. “You may not agree with that assessment. But it is nonetheless a reality for nearly half the country. … Even if you do not share that conviction, it is the responsibility, I believe, of this office to acknowledge that it is a profound threat to this country and to the legitimacy of any administrations that will come in the future.”

Within a very short span of time that day, it became readily apparent that the threat to the country was not that the baseless fears of election fraud held by Trump supporters were not being treated seriously but, instead, that they were granted far too much leniency by Trump and Cruz and many others. Some of the people who thought the election was rigged also thought the appropriate redress was the violent takeover of the Capitol.

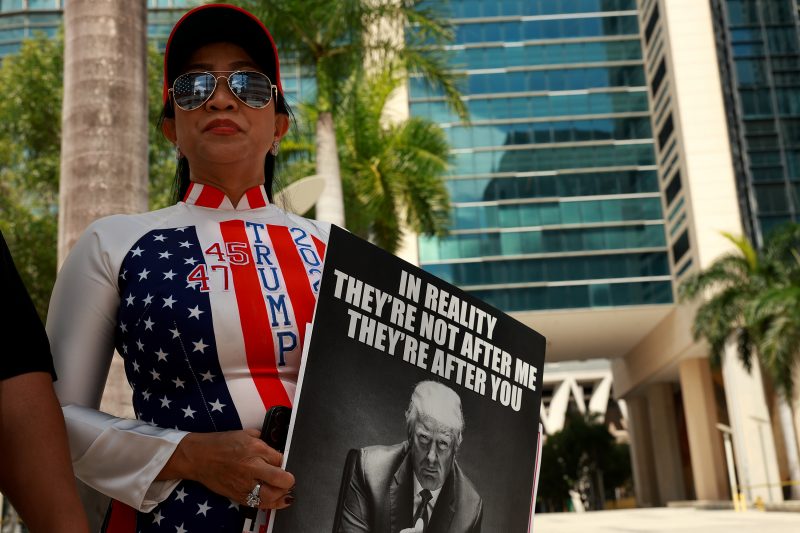

Some of those who believe that Trump’s indictment is a demonstration of unfair political bias, as Graham insisted to Stephanopoulos, are on their way to Miami, where Trump will be arraigned Tuesday.