Washington did this week what Washington had to do, defusing the debt ceiling issue before calamity struck. The legislation also marked a moment of bipartisanship in a badly divided political environment. Whether it speaks to broader questions of governing is quite another matter. On that issue, skepticism is in order.

First the positive analysis. The center held, at a time when there often seems to be no center left in American politics. In truth, the center was bigger than anyone anticipated. The vote in the House was especially notable: 314 votes in favor of a deal that satisfied almost no one and with a supermajority of the fractured House Republican conference voting in the affirmative. In the Senate, there were 63 votes in favor. The hard left and hard right were on the sidelines in dissent.

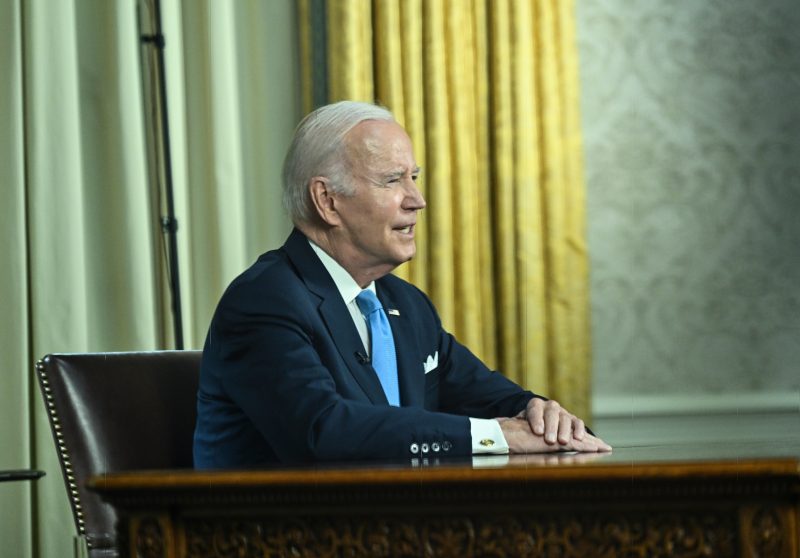

This was governing the old-fashioned way, with public messaging by President Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) aimed at blaming each other’s side for the crisis while their negotiators were given space and authority to deal with one another in good faith. The negotiators produced something that each side could claim met at least some of its objectives, most of all, averting financial disaster.

The final product was not exactly splitting the difference, but more a recognition of the red lines on each side and how not to trample them. Biden can claim that he protected vital programs and priorities from deeper cuts. McCarthy can claim he forced Biden to give ground on spending and on other policy points.

The debate about who won or lost more can continue but the majorities in the House and Senate who backed the compromise speak for themselves as a moment of consensus. As Jennifer Victor of George Mason University put it, “It’s how politics is supposed to work, a return to normal partisan governing.”

Biden once again showed that his commitment to working across party lines is genuine. From the early days of the 2020 campaign up to the present moment, he has never wavered in his conviction that cooperation is possible, occasionally at least, even in a divided country. It is part of his political DNA, though that DNA also includes a sharp partisan edge that was on display throughout the debt ceiling saga.

When Biden talked in his campaign about unifying the country and seeking bipartisan cooperation with Republicans in Congress, many called him naive or dismissed him as an aging politician yearning for a bygone era. Good luck with that, Joe, they said. But he stuck to it. He can now point to this agreement, in addition to the big infrastructure law and the significant semiconductor measure, both of which were approved during the last Congress, as evidence that his vision for bipartisanship can be realized.

Biden also has demonstrated anew an understanding of the rhythms of legislative dealmaking, no surprise given the 36 years he spent in the Senate. There were times not many weeks ago when the two sides seemed to have irreconcilable differences, with Republicans and Democrats firmly dug in. But his public optimism about an eventual resolution once the negotiations began was an example of what long experience brought to the table.

McCarthy fooled many of his doubters as well. He had labored to win the speakership (15 ballots!), cutting deals with hard-liners like Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.) to get the power he so badly wanted. His hold on that power was seen as fragile, seemingly hostage to members of the Freedom Caucus. He had left himself vulnerable by giving any dissatisfied member the right to demand a new election for speaker if he committed some perceived political transgressions.

For a time, the hard-liners seemed in control. McCarthy bowed to them in the early months, as the House crafted and then approved a debt limit bill to their liking. The measure included significant spending cuts that only seemed to underscore the size of the gap between the two sides. But that bill changed the dynamics of the conflict.

Biden wanted a clean debt limit bill and said that was nonnegotiable. Passage of the House bill in late April forced his hand. Maybe Biden knew that was inevitable, given that Democrats no longer had the majority in the House. Once the deal was struck with the White House and the votes were needed to approve it, McCarthy held firm against the most conservative faction in his conference who opposed it and rallied the rest of the Republicans to produce overwhelming support for the final package.

So two cheers for bipartisanship. But no one should get carried away. Republicans manufactured a crisis by using the danger of default and the damage that could have been done to the economy to demand what they could not have gotten otherwise. They insisted on concessions from the Democrats simply to do what previous Congresses have done repeatedly, which is authorize payment for past spending by giving the government more power to borrow money. The debt ceiling has nothing to do with future spending, only with what previous Congresses have already spent or authorized to spend.

Republicans knew the only leverage they had was to tie it to something with a deadline. As in the past, when Congress has faced a hard deadline, things usually get done. This time around, however, it was not a foregone conclusion because of questions about McCarthy and his ability to keep his members in line. “It was an engineered crisis, given Republicans’ demand that Democrats pay a ransom to secure an increase in the debt ceiling,” Sarah Binder of George Washington University and the Brookings Institution said in an email.

Despite his protestations about not negotiating over raising the debt ceiling, Biden had done so in 2011 when the White House and the Republican-controlled House were fighting over raising the government’s borrowing power. As vice president, he had started those negotiations and then when talks between President Barack Obama and House Speaker John A. Boehner (R-Ohio) collapsed, he helped put together the package that eventually was approved after those bigger negotiations collapsed.

The 2011 experience ultimately produced a messy and unsatisfying outcome, but initially, at least the two sides were talking about something significant and ambitious, a “grand bargain” that would have married changes in entitlement programs with new taxes as a way to deal seriously with deficits and debt.

This year, there was no such talk. Biden and the Democrats were unwilling to deal with entitlements as part of the debt ceiling. Republicans took that issue off the table early, after Biden snookered them during his State of the Union address. Republicans also would not consider taxes. Compared to 2011, this was lots of wrangling over relatively small things. The changes approved this time will have little real impact on the overall budget or national debt.

Political scientists Victor, Binder and Nolan McCarty of Princeton University shared the view Friday that the deal, while necessary and perhaps inevitable, does not foreshadow future cooperation in addressing and resolving big problems. It is not even on a par with some of the recent bipartisan bills on infrastructure, semiconductor manufacturing or coronavirus relief, Binder said.

“I wouldn’t code this one as much of a triumph of bipartisanship in the traditional sense,” McCarty wrote in an email. “Basically, the debt ceiling had to come up and both sides needed a partisan, face-saving way to get there.” He was also less optimistic about the ability of the parties to tackle tough financial questions. “As for the general climate, it seems about where it has been for a while,” McCarty added. “Congress can act when it has to, but lots of issues will continue to fester with inaction.”