On May 26, 1647, Alice “Alse” Young was ordered to Hartford, Conn., to be hanged. Young, a botanist, was accused of using witchcraft to start a pandemic that resulted in children’s deaths in nearby Windsor.

Young, who was roughly 32 years old, was the first of at least 11 people put to death for witchcraft in Connecticut.

On Thursday — nearly 376 years after Young’s death — Connecticut’s Senate passed a resolution absolving dozens of state residents who were accused, convicted and executed for the crime of witchcraft in the 1600s.

Generations later, there was celebration from the relatives of those accused. Susan Bailey, Young’s ninth-great-granddaughter, who lives in Hartford, was relieved to receive an apology.

“It doesn’t matter that it was so long ago; it was somebody’s life that was taken unjustly,” Bailey, 67, told The Washington Post. “It may not help her in the afterlife, but maybe it will. But the relatives of hers that know about her terrible death … will gain some peace from it. It will help the healing process.”

In the 16th and 17th centuries, many people believed that witchcraft was the cause of some unexpected deaths and illnesses. It was a crime punishable by death in many states and countries. While the records from that time are incomplete, experts estimate that about 50,000 people worldwide were killed after facing witchcraft accusations.

Modern-day lawmakers across the world have since worked to exonerate people of those crimes. The Spanish region of Catalonia pardoned its residents’ witchcraft crimes in January 2022. In March of that year, Scotland’s first minister issued an apology to residents who were accused of witchcraft. The final Salem Witch Trials conviction was overturned this past July.

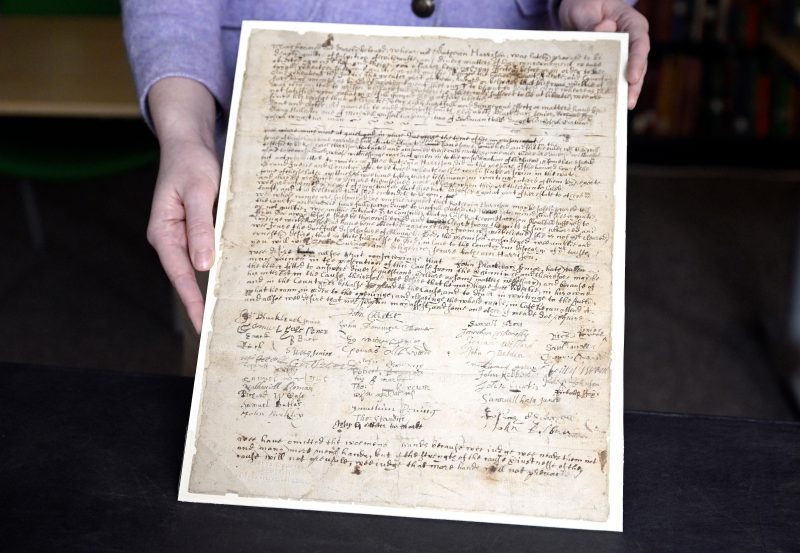

In the past decade in Connecticut, people whose relatives were harmed by witchcraft charges have pushed for the accusations to be expunged. Witchcraft executions in the state occurred between 1647 and 1663 and often took place at a central gathering spot in Hartford, now the location of Connecticut’s Old State House.

At least 34 people were indicted on witchcraft charges, and many fled the state with their families, according to the Connecticut Witch Trial Exoneration Project.

Young’s daughter, Alice Young Jr., was about 7 when her mother was killed. Residents raised her until she married and had about a dozen children. Through DNA testing, Bailey learned around March 2021 that she was a descendant of Young.

Bailey had learned about Young through her newly found relatives and her friend Beth Caruso’s book, “One of Windsor: The Untold Story of America’s First Witch Hanging.” She realized how lucky she was to be alive, but also how frightening it was to have walked many times by the place where Young was killed.

“To find out that part of me really does go back so far … it was just kind of a cool feeling,” Bailey said, “but sad at the same time to find out that your relative was executed.”

Bailey connected with other people who were related to women accused of witchcraft. Sarah Jack learned through Ancestry.com that Winifred Benham was her ninth-great-grandmother. Benham and her daughter were indicted on charges of witchcraft in Connecticut in 1697 before fleeing to Long Island.

A group of more than a dozen distant relatives spoke with and testified in front of lawmakers about erasing their ancestors’ charges. In January, state Sen. Saud Anwar (D) introduced a bill that would do just that. In the following months, Anwar heard from families about the trauma they still endured from their relatives’ hangings.

“More and more people were understanding the relevance of what we were asking,” said Jack, 47. “It’s not just because we want someone to tell us they’re sorry. We want everyone to start acknowledging that that type of targeting towards vulnerable women or men or children isn’t acceptable.”

On Thursday, relatives of accused witches gathered in the Capitol in Hartford. Jack expected the resolution to pass, but she still felt excitement each time she heard a senator vote in support of it.

The bill passed with a 33-1 vote. Senators waved and smiled to the group in the audience as distant relatives hugged and cried.

“It’s never too late to do the right thing, and here it was very concerning that it was over 370-some years ago that people in our state … were murdered because of a reason that has no moral standing,” Anwar said. “There was no legal standing. And it was something that made me sad because it truly has been a stain on our history.”

Some relatives still want Connecticut to build a memorial for the victims and to feature their stories in a museum. Still, they feel relieved to know their ancestors’ names won’t remain stained by crime.

“It’s a long time coming,” Bailey said. “But it was worth waiting for.”