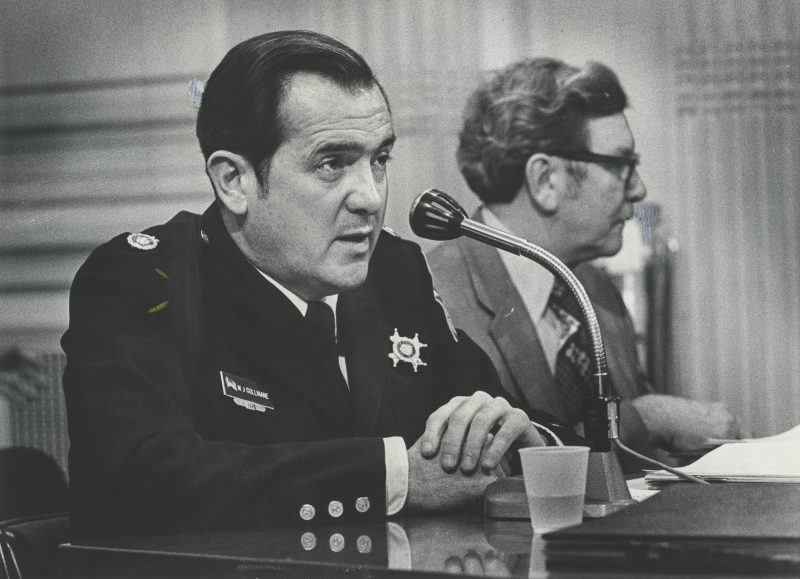

Maurice J. Cullinane, who served as chief of the D.C. police in the mid-1970s and helped negotiate an end to a deadly hostage siege by radicalized members of the Hanafi Muslim sect, died March 2 at a hospital in Bethesda, Md. He was 90.

The cause was complications from a stroke, said his daughter Patricia Carr.

Mr. Cullinane, a native Washingtonian known as “Cully,” followed his father, two great-uncles and other relatives onto the D.C. force in 1955 following Navy service in the Korean War. In December 1974, Mayor Walter E. Washington tapped the soft-spoken Mr. Cullinane to lead the department, then two-thirds White but serving a city that was 70 percent African American.

During his tenure, which lasted until January 1978, Mr. Cullinane was credited with providing steady leadership as the District rebuilt from the devastation of the 1968 riots following the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. Mr. Cullinane was a lieutenant during the upheaval and carried out orders to make sure officers did not open fire or brutally confront those involved in the mayhem.

Two years later, he suffered a debilitating injury during a demonstration against the Vietnam War when he said he was hit with a brick on his left knee, contributing to his early retirement.

He continued new departmental practices started by his predecessor, Jerry V. Wilson, that included engaging more with the community to foster trust and hiring minorities to make the force more reflective of its community. Wilson had reportedly groomed Mr. Cullinane for the chief’s position by promoting him into high-profile and sensitive jobs, including one overseeing the department’s budget.

As chief, Mr. Cullinane led the department through one of the city’s most traumatic episodes when, in March 1977, about a dozen members of a fanatical Muslim sect armed with shotguns and swords simultaneously stormed the B’nai B’rith building, the Islamic mosque and the city’s administrative building.

The “Hanafi Muslims” took 124 hostages, fatally shot a radio reporter, and wounded then-D.C. Council member Marion Barry and a protective service officer, who died days later after a heart attack.

The leader of the operation was Hamaas Abdul Khaalis, a District resident who had formed the Hanafi group. He was long prone to incomprehensible rants, often targeting the Nation of Islam and other Black activist groups. In an attack in 1973, six of his relatives were killed execution-style in his home, and his 9-day-old grandson was drowned in a wash basin.

Five men from a militant Black nationalist group from Philadelphia were convicted of the killings. But Khaalis became increasingly unstable in his grief. He stockpiled weapons in his home and recruited fellow followers of the Hanafi sect to carry out the hostage takings, to draw national attention to the slayings of his family and what he perceived as a lack of attention by government officials to the crimes.

“President Nixon mourned the death of President Johnson, but not my family,” he said, according to the New York Times. The group’s central demand was that authorities free the defendants convicted of killing his family so that the group could exact its own form of justice.

The hostage drama played out over the next 38 hours, with Mr. Cullinane in charge of negotiating an end. He refused the group’s demand to release the killers of Khaalis’s family. But at one point Mr. Cullinane shed his gun and met face-to-face with Khaalis in the foyer of B’nai B’rith, seven floors below where 104 hostages were being held.

With him were ambassadors from Egypt, Iran and Pakistan; some of the hostages were from those countries. President Jimmy Carter reluctantly agreed to let the diplomats take part in the operation, after expressing deep concern about the risk of having foreign emissaries meet with a terrorist.

“I absolutely had none of the problems that people would generally assume you would have,” Mr. Cullinane later told The Washington Post, speaking about turf battles and political interference from the White House and other government agencies. “Everybody deferred to the department’s judgment. There was no attempt on anybody’s part to take it over. Maybe nobody else wanted it.”

In the end, Mr. Cullinane cut a controversial deal. In exchange for an agreement to surrender and release the hostages at all three buildings, the police chief assured Khaalis that after he was arrested, he would be set free on bail to await his trial. Khaalis was convicted of armed kidnapping and conspiracy and died in prison in 2003.

The deal drew criticism, including from the police chief in neighboring Montgomery County, Md., who said police should deny all requests from hostage takers. Mr. Cullinane at the time dismissed that position as “stupid.” In a 2019 interview for this obituary, Mr. Cullinane repeated what he had said over the years: “If you’re going to keep any credibility for the future, then you’ve got to keep your promises.”

Mr. Cullinane was credited with achieving an astonishing trifecta of popularity with the force, the media and large swaths of the community.

“No chief should stay more than four or five years,” he told The Post a year after retiring on disability for his knee problem. “Because once you’ve been there that long, you’ve shaped the department in your own image; it is a reflection of your idea. Once that happens it’s impossible for you to recognize the problems that are there and see the flaws, because you probably created those problems or flaws.

“After four years, most guys want out anyway,” he added. “You’re in a very exposed position. You always have to be covering your flanks on all sides. It’s exhausting.”

Mr. Cullinane was succeeded by Burtell M. Jefferson, the District’s first African American chief.

Maurice John Cullinane was born in the District on Nov. 29, 1932. He graduated from Calvin Coolidge High School in 1950 and, while chief, received a bachelor’s degree from American University in 1977.

In 1956, he married Carole West. In addition to his wife and Carr of Edgewater, Md., survivors include daughters Debra Bitonti of North Potomac, Md., and Joanne Crow of Laytonsville, Md.; a sister; 13 grandchildren; and 13 great-grandchildren.

After Mr. Cullinane left the police department, he became executive vice president of what became the Washington Bankers Association and later ran a private consulting firm. He also served on the board of directors for Heroes, a nonprofit organization that supports families of police officers and firefighters killed in the line of duty.

Mr. Cullinane seemed marked from an early age for prominence on the force. In 1957, Washington Daily News photographer William C. Beall captured the young, lanky Mr. Cullinane helping to calm and protect a 2-year-old boy as firecrackers went off during a parade in Washington’s Chinatown neighborhood.

The image — which Beall called “Faith and Confidence” — won a Pulitzer Prize and has been widely reprinted over the decades.

“He was the kind of cop that was approachable,” said Charles H. Ramsey, the District’s police chief from 1998 to 2006, adding that Mr. Cullinane was ahead of his time in calling for a community-based policing model. “He is leaning over to talk to that boy — that was real. It showed how one viewed police and how police viewed their role. And that is having a good relationship with the people we serve.”

Mr. Cullinane, who was often asked to autograph copies of the photo, offered another interpretation of the scene. “That picture is not of me,” he said in the 2019 interview. “I’m almost like a prop. That is a picture of that little boy.”