There are a lot of different jobs in the world, the products of which are entirely shielded from public scrutiny, subjected to it constantly or something in between.

Most people’s jobs land somewhere near the former end of the scale. What they do happens mostly internally; in fact, there are often enormous pressures to ensure that’s the case. Businesses are willing to accommodate internal mistakes far more than external ones.

Elected officials sit closer to the other end of the spectrum. A lot is public and publicly scrutinized, but there are quiet maneuverings and decisions that are mostly shielded from view. There are mechanisms to expose many of them — Freedom of Information Act requests, intragovernmental scrutiny — but usually they aren’t exposed, and usually there’s no need for them to be.

Then there’s the media, of which I am a nonobjective member. The media’s work is largely public; nearly everything I’ve done as an employee of The Washington Post, for example, is still available for your perusal. Here, too, there are internal discussions and actions, but those almost always lead to some public presentation.

Now consider what happens when a mistake is made. As noted, private-sector companies are eager to shield those mistakes from view, though there are likely to be internal consequences. Elected officials will instinctively scramble to protect themselves, efforts whose success depends on the scale of the mistake. Sometimes, the best way to preserve one’s reputation is to admit guilt. Sometimes, the best way is to blame someone else.

Then there’s the media. Most media outlets (admittedly not all) aim to correct mistakes rapidly and accurately and to do so publicly. Even small fixes can lead to an article being accompanied by a little blurb of explanation. Large fixes, meanwhile, can lead to public retractions or apologies. This is uncomfortable for the writer in part because it is a black mark for their employer in a way that political scandals generally aren’t and in a way that businesses are desperate to avoid.

The disparity between how the media and other institutions operate has proved to be a disadvantage for journalists. Increasingly, isolated mistakes are cherry-picked from an extensive catalogue of reporting to cast a media outlet as inherently suspect. Those corrections or clarifications that are intended to provide transparency also provide ammunition for critics. The process of seeking corrections has itself been corrupted by bad-faith actors who nitpick small issues and, if a correction is made, trumpet the change as further evidence of the media’s corruption. Meanwhile, dishonest actors in the media simply refuse to admit their mistakes, meaning that efforts at accountability collapse into they-said, they-said debates over accuracy.

This articulation is useful in the moment because of a pair of politically fraught conversations about free speech in the United States. The first was a discussion helmed by Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) in that state on whether the free press was too free. The second unfolded in Washington on Wednesday, as the House Oversight and Accountability Committee considered whether the social media platform Twitter had unacceptably suppressed speech. In each case, Republican officials were demanding a reexamination of elements of the First Amendment and, in each case, were (ironically) leveraging the power of government to try to reshape the sort of speech that should be allowed.

In Florida, DeSantis hosted a group of lawyers, conservatives and individuals who had challenged the media for a discussion on loosening the standard that protects news organizations against defamation lawsuits. The group focused on New York Times Company v. Sullivan, a 1964 Supreme Court decision that established a standard mandating, among other things, that deliberate malice be shown. It’s not enough for reporting to have been mistaken; it must have been deliberately wrong.

Protection of the press is, of course, written into the First Amendment — but that protection centers on avoiding government interference. The standard under Sullivan offers a different protection, helping news outlets avoid frivolous or overwrought lawsuits generated for punitive reasons. This is not an idle threat; billionaire Peter Thiel funded a lawsuit against the website Gawker that eventually bankrupted it — an act centered not on the incident at issue but, instead, on his own animus toward the site.

Were the bar for successfully suing a news organization not high, there would be far more lawsuits. The effect would be to drain organizational resources — but also to chill critical reporting.

That would certainly appeal to DeSantis, but it’s likely that his focus was more on playing to conservatives who view the media as dishonest, hyper-liberal or both. The discussion included inaccurate assertions (such as DeSantis’s claim that the question of Russian interference in 2016 and contact with Donald Trump’s campaign was “all eventually … debunked”) as well as examples of media overreach plucked from years of accurate reporting, presented as cases of inherent dishonesty and inaccuracy.

Notably, the examples of purported media bias cited by attendees had resulted in corrections or changes to reporting and, as evidenced by the hearing itself, continue to inflict damage on institutional reputations. But what was desired by those hosted by DeSantis was, instead, financial punishment — the sort of thing that can more immediately hobble a news outlet.

This event centered on an elected leader soliciting suggestions for ways in which the free press could be constrained. That leader was doing so very obviously because he’s considering a presidential campaign and hopes to demonstrate his anti-media bona fides to Republicans. And to blunt any critical coverage of his tenure or campaign as inherently biased.

“People here trust me a hell of a lot more than they trust the media,” he said at one point in the discussion. “So it ends up being fine.”

The following day, House Republicans, newly in the majority, delivered on one of the central promises they’d made to their cable-news constituents: challenging Twitter for having blunted free speech, perhaps with the aid of corrupt government actors.

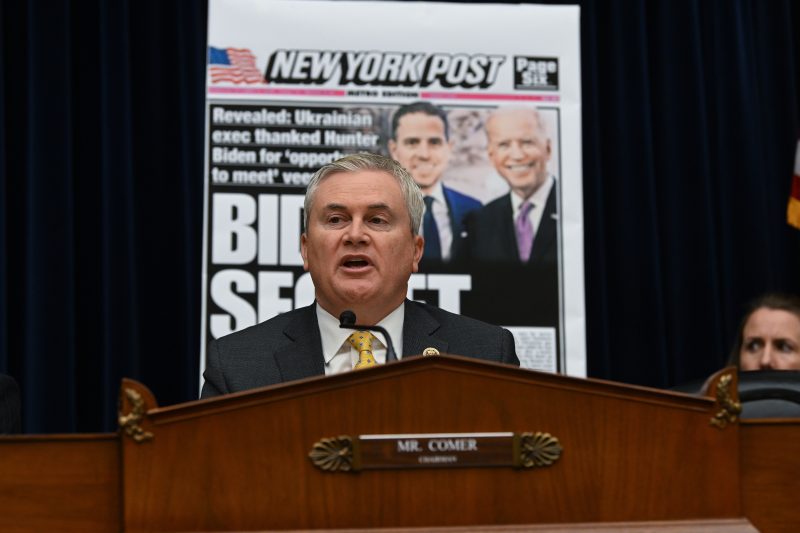

The hearing was focused on a now familiar narrative: Twitter briefly muted discussion of a controversial New York Post story about the laptop of President Biden’s son Hunter in the weeks before the 2020 election, an egregious overstep of its mandate. This one act has been useful enough to be looped into a number of other Republican lines of rhetoric, like that the 2020 election results were skewed by malicious liberal interference (as by Twitter) or that the FBI sought to hobble Trump’s reelection by encouraging Twitter to mute the subject. Neither of these lines of argument is accurate, but you can see how this all fits nicely together.

Wednesday’s hearing did include some new revelations, including that the Trump administration had sought to have a critical tweet from model Chrissy Teigen deleted. This undercut the idea that efforts to control Twitter’s content was a function of left-wing actors, and helped demonstrate the lack of evidence that any institution besides Twitter was making decisions about what content to show. In fact, the hearing revealed that Twitter changed its own rules to protect Donald Trump’s account after he attacked Democratic lawmakers in 2019.

It is safe to say that the central trigger for the hearing was the selected release of internal company information once Elon Musk — deeply sympathetic both to the presented line of rhetoric and to the House majority’s politics — bought the platform. In an effort to prove that Twitter was riddled with liberal activists, Musk leaked internal discussions to reporters sharing his position, allowing them to frame a case against Twitter’s actions that often depended heavily on strategic omission.

Consider how this inverts our expectations about what’s public and what’s private! The media’s work is public, subjecting it to scrutiny and bad-faith attacks, but at least we know it’s public. Twitter employees could have assumed that their internal conversations would be private and that the institution on whose behalf they were working would have no interest in making those debates available for scrutiny. Then Musk shows up and does precisely that — in a way that intentionally disadvantages the company’s (now mostly former) employees.

Over the course of the hearing, Republicans repeatedly praised Musk for buying Twitter and fueling this idea that Twitter was a liberal institution bent on harming the political right. The idea was that the new system would somehow avoid the old pitfalls, though Musk’s tenure has been one in which policies are changed for only as long as it takes to make obvious why the original policy was useful.

There are two through-lines to this week’s First-Amendment-related conversations by Republican officials.

The first is that government actors are hoping to change the extent to which private entities can speak freely, by increasing the likelihood that news organizations can be sued or by attacking a social media platform for making decisions about what it hosts on its own platform. This gets much closer to violating the First Amendment than anything Twitter did or didn’t do.

The second is that these attacks largely depend on cherry-picking public information. In the case of DeSantis, that’s the available reporting and infrequent corrections of news organizations. In the case of the House hearing, it’s selectively presented information offered by the new owner of Twitter, letting motivated parties construct narratives from selectively released documents written without any expectation that they would be public.

What the Republicans driving this discussion seek is clear: thorough autopsies of every decision that disadvantages them and their allies and an impenetrable defense against any such scrutiny of their own.