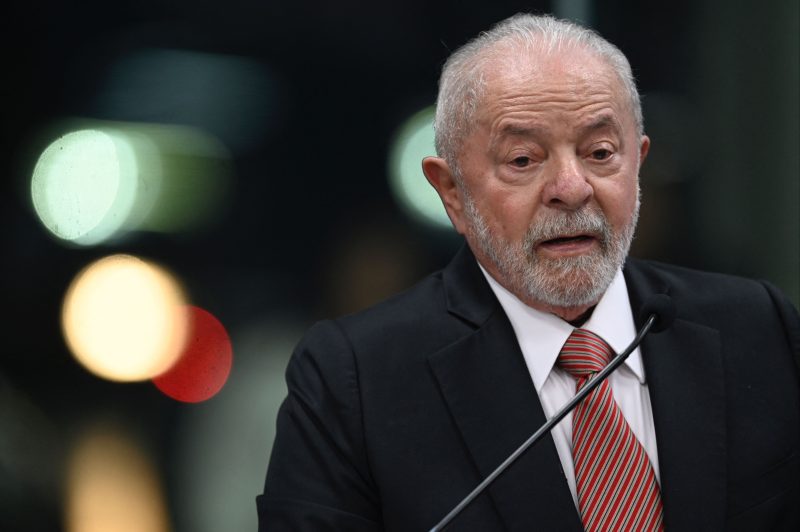

President Biden and Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva might have more in common than they would like.

They’re both their country’s oldest presidents — Biden is 80 while Lula is 77 — who previously served at the highest levels of government.

More starkly, they came to power amid disturbing political turmoil only two years apart. They both campaigned on promises to return their countries to normalcy after four years of sometimes-chaotic rule by populist-style leaders. And they defeated incumbent presidents who refused to recognize the election results as legitimate, leading to insurrections in both their nations’ capitals — one on Jan. 6, 2021, and the other on Jan. 8, 2023.

On Friday, Biden and Lula will meet at the White House in what is intended as an important signal that their democracies are resilient.

“These are two leaders with so much in common, and I think they’re going to talk as much as they can about their shared experiences because that’s what will play best with their domestic audiences,” said Brian Winter, a Brazil expert and vice president at the Americas Society and Council of the Americas.

“Lula wants to point to Biden as someone who defeated an authoritarian, anti-constitutional threat and lived to tell about it,” Winter said. “There’s domestic benefit to Biden being able to point to Lula and say, ‘Hey, the United States is not the only country that has faced challenges from the authoritarian right.’”

Biden and Lula also have a personal relationship, said a senior administration official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to provide details of an upcoming meeting. Biden was among the first leaders to congratulate Lula for his victory, the official said, and he spoke with Lula after the Jan. 8 attack in Brazil and invited him to the White House.

The two are expected to discuss democracy, including “their categorical rejection of extremism and violence in politics,” the senior official said, as well as climate change and economic development.

But there could be tension between the two men when it comes to the war in Ukraine, given their differing views.

Biden has worked to rally support for Ukraine from the global south, arguing that all nations have a responsibility to stand up against a superpower’s unprovoked and bloody invasion of its neighbor.

Lula, by contrast, has said both Russian President Vladimir Putin and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky bear responsibility for the war and has sought to fashion himself a senior statesman who can broker a negotiation between the two countries. He has proposed setting up a “peace club” of countries that could mediate an end to the war, and he has repeatedly rejected calls from Western countries to support Kyiv with weapons and ammunition, saying Brazil does not want an “indirect” role in the conflict.

His stance reflects a widely held view in the global south, where many countries have been especially hurt by fuel and food shortages inflamed by the war and do not want to harm relations with Russia.

There is little appetite for negotiations in the near-term in Washington, where Biden and his top aides have made clear they do not think the conditions are ripe for a peace talks, citing Putin’s bombardment of Ukrainian civilian infrastructure and evidence of war crimes. They have said they will not force Ukraine to negotiate before its leaders are ready.

The two men are also unlikely to see eye-to-eye on China, which Biden views as the biggest long-term threat to American interests. The United States and China are in the middle of a diplomatic skirmish after the Pentagon discovered an alleged Chinese spy balloon that the United States shot down last week.

Lula, for his part, has sought to forge closer relations with China, a major trading partner of Brazil. He plans to visit the country in March, a trip that Brazilian officials say is occupying more of their time and will have a more robust agenda than this week’s meeting with Biden.

Lula, a lodestar of the Latin American left, came to power in October in the closest presidential election in Brazil’s history with ambitious pledges to protect the Amazon rainforest, tighten gun laws and ease hunger and poverty in a country rife with income inequality.

His victory in the race — one marred by a mix of disinformation and conspiracy theories that echo recent developments in the United States — marked a striking comeback for Lula. Previously president of Brazil from 2003 to 2010, he was convicted on corruption charges after leaving office and spent 580 days in prison before his convictions were thrown out in 2021.

Like Biden, Lula also has a reputation for pragmatism and reaching across the aisle to work with moderate members of the opposition. Both men must now govern bitterly divided nations.

“They are very seasoned men who are … tasked with the mission of bringing peace to their countries,” said Dawisson Belém Lopes, a political scientist at the Federal University of Minas Gerais. “I don’t know if they will live up to this daunting task, but this is what people expect from them at the moment.”

Bruna Santos, a fellow at the Wilson Center’s Brazil Institute, said Brazil and the United States are “looking each other in the mirror, because we have been facing challenges toward the rule of law and our institutions that are very scary.”

In contrast to the deliberate pace with which U.S. authorities have moved to investigate former president Donald Trump’s role in the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, officials in Brazil quickly opened a probe into outgoing president Jair Bolsonaro’s role in the violent attack in their capital last month. Like Trump, Bolsonaro, who some political analysts have called “the Trump of the Tropics,” skipped his successor’s inauguration and headed to Florida.

The former Brazilian president has condemned the violent attack in Brasília and denied any role in it. Several of his former allies have been arrested or are being investigated for their roles in the riot.

Bolsonaro recently applied for a 6-month tourist visa to stay in the United States. Democratic lawmakers have urged Biden to cancel any visa that Bolsonaro might be using to stay in the country. Brazilian officials have said it’s unlikely that Lula will raise the subject with his American counterpart.

Lula is expected to travel to Washington with a small coterie of cabinet ministers, including those in charge of the economy, environment, human rights and foreign affairs. He has been frustrated by what he sees as a lean agenda for the meeting, according to two Brazilian government officials who spoke on the condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak publicly.

The Brazilian leader also plans to meet with several U.S. lawmakers, including Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.), and members of the AFL-CIO. Like Biden, Lula has close ties to unions in his country.

Officials in Brazil have conceded privately that they expect few, if any, major announcements from the meeting, except for a potential agreement on the Amazon Fund, which aims to prevent deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. Rather, they cast it as an opportunity to reset the U.S.-Brazil relationship following the Trump-Bolsonaro era and to build a foundation for stronger ties in areas where there is policy alignment, such as combating climate change, protecting human rights and safeguarding democratic institutions.