WASHINGTON — Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine) was basting her Thanksgiving turkey when Sen. Thom Tillis (R-N.C.) gave her a call with an important update: He had made progress in their effort to convince more Senate Republicans to vote for their bipartisan legislation to protect same-sex married couples.

“He’s always working on it,” Collins said of the second-term senator. Her husband pleaded with her to get off the phone and focus on Thanksgiving, but less than a week later, the bill passed with 12 Republican votes — thanks in part to Tillis’s relentless focus.

“He is an extraordinarily good vote counter,” Collins said.

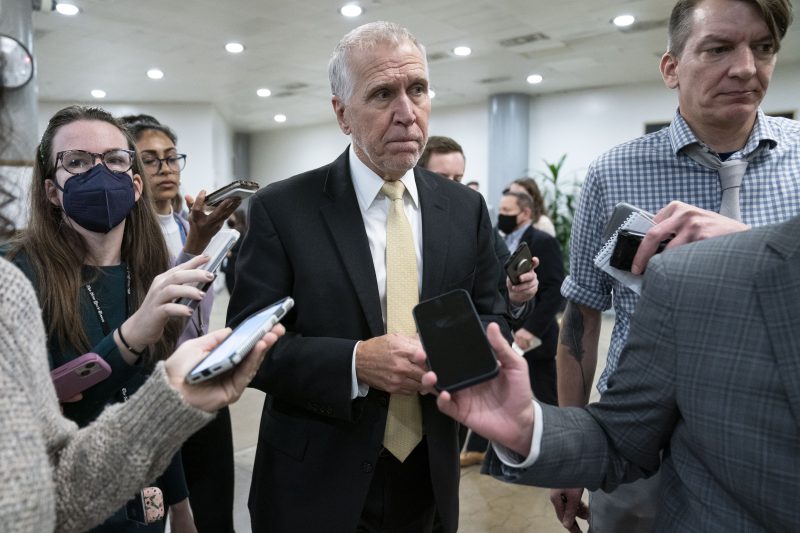

Over the past year, Tillis has muscled his way to the heart of nearly every major bipartisan effort to emerge from the evenly-divided Senate, taking a lead role in negotiating legislation on hot-button issues including gay rights, guns and immigration — all without drawing much attention to himself.

It’s a politically tricky trifecta that few Republicans — many fearing primary challenges from the right — would want to touch. But Tillis’s willingness to find compromise despite the political blowback is desperately needed, his colleagues say, as a wave of retirements has taken many more bipartisan-minded lawmakers out of the chamber just as it needs to find a way to compromise with a narrow and fractious House Republican majority that barely managed to elect a speaker earlier this month.

“I see him as stepping into what otherwise would be a bit of a void because of the loss of those members,” said Collins, referencing the retirements of institutionalist Republican Sens. Rob Portman of Ohio, Richard Burr of North Carolina, Richard C. Shelby of Alabama and Roy Blunt of Missouri, who all at times helped forge compromises to keep the government running.

A hard-right faction of House Republicans have extracted concessions from newly elected Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) that make showdowns over lifting the debt ceiling and funding the government more likely next year — putting even more pressure on the shrinking pool of lawmakers like Tillis who can forge compromise.

“It is really worrying that people like Rob Portman are leaving,” said Sen. Chris Murphy (D-Conn.). “And my hope is that people like Thom and others will step up to help make the Senate work.”

But Tillis, a former management consultant who jumped into local politics 20 years ago and later quickly climbed the ranks in the North Carolina State Legislative Building to become its speaker, rejects the label of “dealmaker” and emphasizes the conservative stamp he’s placed on the legislation he’s worked on. He describes his decision to help craft compromises as driven not so much by an affinity for centrism but by a frustration with the inability of some of his co-workers to effectively work together. He chooses the issues he wades into carefully and with an eye to their impact on his career.

“I don’t believe in this kumbaya, everybody-be-happy, lets-all-be-bipartisan [thing],” Tillis told The Washington Post in an interview. “I think you’re bipartisan on a transactional basis. If you’re always bipartisan then you’ve lost your mooring on your ideological worldview.”

Nevertheless, Tillis has had his hand in nearly every bipartisan piece of legislation to emerge from the Senate in the past year and a half: from the $1 trillion infrastructure package, to the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act that expanded background checks for some gun buyers that passed in the wake of the school shooting in Uvalde, Tex., to the Electoral Count Act that updates the presidential certification process to avoid a repeat of the pressures President Donald Trump put on his vice president, Mike Pence. (Tillis did not vote to convict Trump during his second impeachment for his role in that event.)

Murphy, who worked with Tillis on the first significant gun legislation to pass the chamber in 30 years, said Tillis had an intuitive grasp of what would get individual Republican senators to “yes,” allowing the group of negotiators to move quickly. It’s a skill Tillis honed during his years as speaker in North Carolina.

“Thom was relentlessly in touch with his caucus,” Murphy said. “Between our negotiating sessions I would watch him: Thom would walk around the Senate floor and talk to Republican after Republican about the things we were discussing, probing what could get 60 votes and what couldn’t.”

When he’s working on a bill, Tillis keeps track of where his colleagues land on certain provisions by scribbling on an oversized index card that he keeps in his jacket pocket, Collins said, noting whose vote is gettable and what it would take to lock it in.

On the gun bill, Tillis quickly divined that banning assault weapon purchases for people under 21 would not get the necessary 10 Republican votes for passage, allowing the group to move on to other provisions.

And Tillis was also a tough negotiator when it came to ensuring due process protections for gun owners, Murphy said. (He also wasn’t sure Tillis himself would have supported the limited assault weapons ban. “Thom is real conservative,” Murphy said.)

Working with Democrats has led to some blowback from conservatives back home, as some Republican base voters view any compromise as sacrilege. But Tillis doesn’t seem worried — he’s done the political math.

For Tillis, a high compliment for a piece of legislation is that it will “age well.”

The same-sex marriage bill? It’s going to age well, he says, pointing out that the protections for religious organizations in the bill were rock solid. The gun legislation that the NRA said would “infringe upon the rights of law-abiding Americans?” It will age well, too, he says, given the Justice Department says it’s already allowed authorities to stop people with serious criminal backgrounds from purchasing weapons, and Second Amendment rights have not been infringed.

Tillis makes these political calculations carefully. And unlike some legislators who tout their political courage in forging consensus around tough issues, Tillis candidly says he has never voted for a bill that he believed carried a significant risk to his job. One of his final votes of the last Congress was to oppose the bipartisan $1.7 trillion federal spending law that had become a punching bag on the right.

“I don’t vote for anything that I honestly believe will have a serious political consequence,” Tillis said. “I should say I haven’t. I may. If I got to a point where I felt strongly about something.”

Paul Shumaker, a Republican political consultant in North Carolina who’s been advising Tillis for years, said Tillis’s bipartisan work could help him in the purple state, which Barack Obama won in 2008 but has voted for the Republican in every presidential contest since. Tillis won his Senate seat by less than two percentage points in both 2014 and 2020 after grueling and expensive races.

“Thom Tillis’s focus is always about winning,” Shumaker said. “I would make the argument if you look at North Carolina today … he’s strengthening his standing in his state with all voters.”

“North Carolina is the swingiest of all swing states,” he added.

While Tillis often speaks of his legislating in businesslike and transactional terms, Murphy said in the wake of the horrific deaths of children in Uvalde, he saw someone moved to reassure Americans that Congress could actually work.

“I did get the sense from Thom that he thought the moment after Uvalde was a bit of a test of our democracy,” Murphy said. “This was an issue that a lot of people cared about and a lot of parents really cared about … It didn’t feel like a moment where nothing could be the answer.”

And Tillis was beaming after the gun bill passed with 15 Republican votes on the Senate floor.

While facing the prospect of a primary in 2020, Tillis seemed more constrained in the Senate than he does now. In 2019, he wrote an op-ed for The Post declaring he opposed allowing Trump the power to declare a national emergency to build a border wall.

“It’s never a tough vote for me when I’m standing on principle,” he told The Post at the time. Just a few weeks later, facing an uproar from Republican voters, he did an about face and voted to stand with Trump on the emergency declaration. Tillis also walked away from nascent talks on exchanging increased border security for a lengthy path to citizenship for some Dreamers — people who lack legal immigration status but have been living in the United States since they were children. Conservative media outlets blasted any such move as “amnesty.”

Rage over Tillis’s brief stand against Trump powered a primary challenger from the right, in the form of retired businessman Garland Tucker. But Trump then endorsed Tillis along with all incumbent GOP senators, dashing Tucker’s hopes, who dropped out.

Since winning reelection, Tillis has taken on a higher-profile role in the Senate in more ways than one. He personally helped raise money for a Republican challenger to former Rep. Madison Cawthorn (R-N.C.), who lost his primary bid following a string of scandals and after insulting the state’s junior senator as a “RINO” (Republican in name only). It was a flexing of political muscle by Tillis that did not go unnoticed back in North Carolina.

And this year, he’s joining the Senate Republican leadership team as counselor. “North Carolina and the whole country benefit from his service and I’m glad he’s taking on this new leadership role,” said Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) in a statement.

Tillis has also returned to the issue that previously gave him the most headaches politically: immigration. In December, he and Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (I-Ariz.) worked on a last-minute compromise to give a path to citizenship to Dreamers in exchange for billions more in border security and revisions to the asylum process. Though the proposal did not attract enough support to pass, it drew heated responses from Tillis’s conservative constituents.

Tillis and those who know him, however, say he’s gifted with an ability to compartmentalize that makes it easier for him to withstand controversy. Shumaker recalls Tillis asking him during his first Senate race to call his wife Susan and brief her on any new polling data, so that when he got home he didn’t have to talk about work.

“Some people’s personality is just such that they internalize the criticism,” Tillis said. “I don’t. When I leave this building tonight I won’t think about this stuff until I come back in this building tomorrow. God has blessed me with that.”

Tillis has worked closely with another senator with a gift for blocking out criticism: Sinema. The pair talk as often as six times a day when they’re working on legislation, she said, and Tillis once even dressed one of his dogs as Sinema for Halloween (the other went as McConnell). At one point while they worked on the same-sex marriage compromise, Tillis called Sinema to brief her about the vote count and warn her he was going to be out of cellphone service for a day for a camping trip.

“I’m off the grid for 24 hours. Don’t let it go to hell while I’m gone,” he told her, according to Sinema. During the gun violence negotiations, they talked vote counts while she ran in the desert and he was doing construction in his garage.

“He’s very straightforward. He’s very direct, he doesn’t hide the ball, or move the ball. And those are things I really appreciate,” Sinema said.

But the pair’s last-minute bid to tackle the surge of migrants crossing the U.S.-Mexico border and the plight of Dreamers who could lose their temporary legal status failed in the dying days of December’s lame duck session, and Tillis was clear-eyed in an interview last month about how little hope there is for that kind of compromise now that Republicans have taken over the House. With the precision of a seasoned vote counter, he quickly ticked off the obstacles standing in the way: a House Republican majority who would want even more border security money in the bill to even consider it, and a Senate controlled by Democrats who would demand in turn that a larger population of immigrants be eligible for citizenship, which would poison the effort for Republicans.

“All of those things lead me to believe that it’s highly unlikely that in the next three or four years that we will get anything done,” he said.

On Jan. 9, Tillis joined a bipartisan group of senators who traveled to the border, and said after he planned to try to “work with our House colleagues” to see if there is any possibility of passing legislation. But the new House Homeland Security Committee chairman, Rep. Mark Green (R-Tenn.), called the deal “garbage” and “dead” last week, according to Roll Call.

But House Republicans’ struggle to elect a leader suggests the chamber will need senators who can help forge far more basic compromises to keep the government funded and the federal government’s debts paid over the next two years — or else risk grave financial consequences.

“Republicans in the House are right to say we’ve got to bend the curve on spending, but the real question is okay, what is the path exactly?” said Tillis, who called a default a bad idea. “How do you get it done with the reality of a divided Congress and a Democrat in the White House?”

Some fear an era of shutdowns and dysfunction is beginning, while others, including Portman, named Tillis as an example of a lawmaker who can keep the place functioning. Asked last month if he worried about the place after his own retirement, he said no, that others would “step in.”

“I’d point you to Thom Tillis,” Portman said.