Congressional Republicans confronted sharp internal divisions Wednesday, with clashes over government spending and party leadership underscoring looming challenges in the GOP as it prepares to take control of the House in January.

House Republicans met Wednesday to discuss party rules that will govern their narrow majority next year, including a push by staunch conservatives dangling demands over Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (Calif.) in exchange for votes to support his bid to become the next speaker. The tensions threaten to delay the start of basic House functions, such as proposing legislation and jump-starting investigations into the Biden administration.

“It’s a volatile situation,” Rep. Stephanie I. Bice (R-Okla.) said of the conversation about House rules. “And I think that the majority of the conference doesn’t feel like that’s in the best interest of the body as a whole.”

On the Senate side of the Capitol, a group of Republicans used the conference’s rules to force a meeting to pressure leadership to lay out a vision and direction for the party. Some members have attributed what was widely seen as a disappointing midterm performance to the lack of a more concrete government agenda on the campaign trail. And after a Senate lunch, at least one Republican senator questioned why he and his colleagues were even working with Democrats on government spending.

The strife came as the clock continued to tick on yet another down-to-the-wire negotiation over federal funding. It also reflected the growing uncertainty surrounding the GOP’s ability to unite in the new year amid fractures in their ranks and strong disagreements between hard-right Republicans and their more moderate colleagues.

Congress must act before the end of Friday to avert a shutdown of federal government services. Lawmakers were poised to extend the deadline by at least an extra week, giving them until Dec. 23 to act. The Democratic-controlled House was expected to approve the extension Wednesday evening.

But finding a longer path forward on government funding has been far from smooth. McCarthy led House Republicans in echoing a handful of Senate Republicans who argued for a short-term funding measure until the GOP assumes the House majority in January. They could then immediately work to rein in spending by the Biden administration rather than wait until the end of next year, the thinking goes.

That strategy is worrisome for some congressional Republicans, who privately admit that demands by the far-right flank could make it impossible to agree on basic duties given to Congress. House Republicans will only be able to afford to lose five votes to pass legislation next year.

“I don’t think it’s of the interest of the House Republicans to have a CR,” retiring Sen. Rob Portman (R-Ohio) said, referencing a short-term continuing resolution through January.

A stated desire to lower government spending has driven many demands the rank-and-file have made of Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (Ky.) and McCarthy. McConnell survived a challenge to his leadership post last month by Sen. Rick Scott (Fla.), the head of the Senate Republican Campaign arm. Scott clashed with McConnell during the midterms over how much policy to run on in the campaign.

While most House Republicans are supporting McCarthy for speaker of the House, including former Freedom Caucus chair Jim Jordan (Ohio) and far-right Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (Ga.), his pathway to the top job remains uncertain. McCarthy convened a meeting Wednesday to allow for challengers to air their grievances and make demands over changes to the chamber’s rules.

Ahead of what was termed a “family discussion,” the five hard-right Republicans who have publicly said they would vote against McCarthy for speaker dug in deeper, complicating efforts to splinter them.

Rep. Ralph Norman (S.C.) said that he and Reps. Matt Gaetz (Fla.), Bob Good (Va.), Matthew M. Rosendale (Mont.), and Andy Biggs (Ariz.) — who is mounting a bid against McCarthy for speaker — “come as five” and must be won over by McCarthy for all of them to deliver their votes.

“I don’t think he has the votes,” Biggs said of McCarthy.

Norman said all five have strong concerns over government spending without proper oversight, but some also want McCarthy to reinstitute the “motion to vacate” rule that would allow any member to recall him at any point. It’s a discussion that McCarthy was intent on not entertaining before the midterms, but is now allowing debate to move forward on as he seeks to consider compromising with the right flank.

“I’ve told Kevin this is to his benefit because it shows confidence,” Norman said. “You got to have accountability and the motion to vacate gives accountability.”

Complicating matters is the number of moderate GOP members who told McCarthy on Wednesday that they will vote against any House package early next year that includes the motion-to-vacate rule.

“There is no ‘plan B,’” Rep. Maria Elvira Salazar (Fla.) said, indicating that the moderates will back McCarthy and no one else.

The moderate GOP Governance Group made blue and red buttons that say “OK,” an acronym for “Only Kevin” in an attempt to show their support for McCarthy. But some Republicans mocked the buttons saying that inadvertently says McCarthy is just an “okay” option.

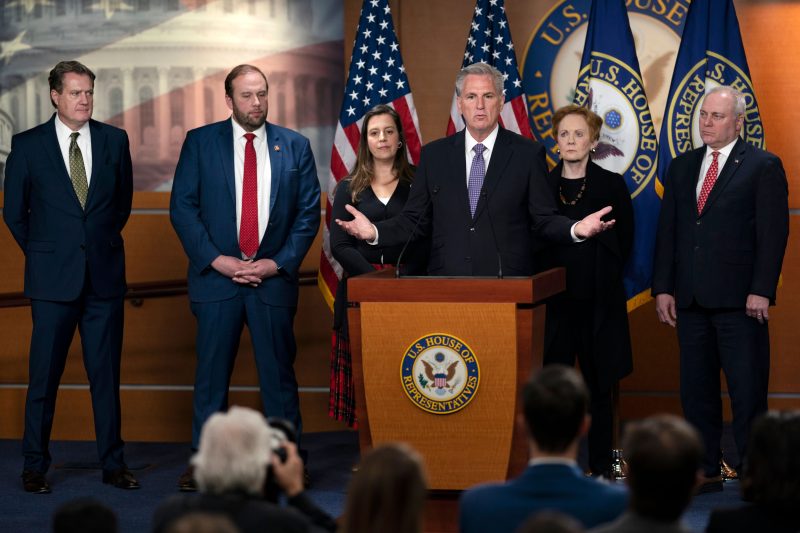

During a rare news conference Wednesday, McCarthy pushed back on questions about whether he was aggressively resisting the funding of the government through next year because it is favored by small group of staunch conservatives who are important to his future.

“What argument did I propose that had anything to do with the speaker?” McCarthy shot back.

Reflecting on the slim House majority to come, McCarthy said: “It doesn’t matter whether we have a 30-seat majority or five-seat majority, we get the same size gavel but we’re going to use it in the manner that the American public wants us to.”

McCarthy also criticized the last-minute funding process, choosing to indirectly attack Senate Appropriations Committee Chairman Patrick J. Leahy (D-Vt.) and the top-ranking Republican on the panel, Richard C. Shelby (Ala.), for influencing the budget talks even though they are retiring at the end of this term.

“If two people who are deciding it aren’t going to be held up to the voters, do you feel good about that as an American?” McCarthy asked.

Unlike McCarthy, McConnell has expressed more openness to a longer-term funding bill extending beyond early next year. On Wednesday, he renewed his calls for any deal to clear Congress by Dec. 22, a day before the expected new deadline at which federal funding is set to run out.

If that doesn’t happen, he said Senate Republicans would only support a temporary stopgap into next year — a move Democrats dislike, since it would force them into tough negotiations with Republicans once they take over the House.

“It will take seriousness and good faith on both sides to produce actual legislation,” McConnell said, pointing out lawmakers face a “challenging sprint.”

Also in the Senate, a group dubbed “the Breakfast Club” called a meeting Wednesday to discuss the vision of the party. Much of the meeting focused on government spending, with senators calling for the party to embrace more fiscal discipline as they have in the past. (Though during the Trump administration, big spending ballooned the deficit.)

Sen. Ron Johnson (R-Wis.) led the discussion with charts and bar graphs about how much the government has spent in the past year, he said. He released to the senators a draft of what the party should stand for and what its goals for the next Congress should be, proposing an agreement for no bill to expand the size of the government, except for defense and to protect the borders.

Senators said it was a good discussion mostly about the future where nearly every member participated.

When it comes to the government spending talks, congressional negotiators from both parties hailed a breakthrough Tuesday, working out what they described as a spending “framework,” which might fund federal operations through the remainder of the fiscal year that concludes Sept. 30.

Even into Wednesday, the architects of that early agreement — Leahy, Shelby and Rep. Rosa L. DeLauro (D-Conn.) — kept its details close to the vest. They shared no information about its spending levels — including the extent to which they planned to provide additional aid for Ukraine.

Instead, they forged ahead with the intricate process of writing the legislation with congressional leaders’ early blessings. McCarthy and top House GOP appropriator Rep. Kay Granger (Tex.) were not part of the negotiations, according to people familiar with the negotiations, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss private deliberations.

McConnell was asked in a policy lunch Wednesday why the senators still don’t know how much money the framework would cost, according to a senator who attended the lunch and spoke on the condition of anonymity to reveal private discussions.

Taking aim at federal spending, Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah) said he didn’t think the ongoing talks were an “appropriate activity for Republicans to eagerly engage in.”

“I don’t know why any Republican, let alone 10, would want to help them do that in those circumstances,” added Lee, who said he spoke with McCarthy earlier in the day.

Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.), who has long advocated for lower government spending and votes against most spending bills, said he hasn’t decided if he’s going to slow down the process of passing a government funding bill before Christmas.

“I haven’t made a complete decision on this week, or next week. Other than that, it’s a rotten, no good way to run your government,” Paul said.