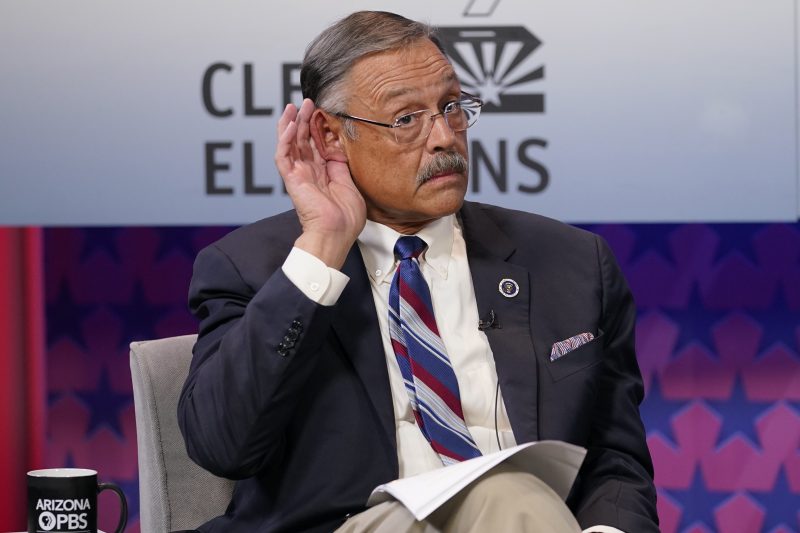

State Rep. Mark Finchem (R) lost his bid for Arizona secretary of state for two interrelated reasons.

The first was that he ran a bad campaign, as The Washington Post noted at the end of October. He had only one paid staffer for his statewide campaign in a state of 7.3 million people. He raised little money and ran only one television ad. His opponent, by contrast, ran a traditional campaign and spent heavily on advertising.

Those ads focused heavily on Finchem’s embrace of former president Donald Trump in the wake of the 2020 election, including that Finchem was just outside the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, as the violent riot was underway. This is the second reason: Finchem repeatedly rejected the legitimacy of President Biden’s win, earning him national attention as an election denier.

In the end, Finchem lost by about 5 points. And almost instantly, he claimed that his loss was a function of voter fraud. He formalized that complaint in a lawsuit filed Friday.

What’s interesting about that lawsuit, though — as was the case with Trump in 2020 — is that it relies on technical complaints and innuendo to overturn the election results, not actual claims of fraud. To the courts, Finchem and other losing candidates offer up a seemingly sober assessment of how the results were somehow questionable. To the public, though, they make baseless claims of illegality both because they’re unbound by the restrictions of legal filings and because it works much better for engagement.

In essence, then, the legal standpoint of the Finchems of the world is that they aren’t election deniers, even as they publicly deny elections.

No one should have been surprised by the results in Arizona. The top three statewide races ended up aligning closely with late polling from Siena College and the New York Times. Sen. Mark Kelly (D) defeated Blake Masters by about 5 points, compared to a 4-point margin in the poll. The sitting secretary of state, Katie Hobbs (D), won the gubernatorial race by just under one percentage point; the poll showed the race tied. In fact, Finchem actually did better than the poll would have suggested — but he still lost handily.

In his lawsuit, he claims this is a function of inadvertent (or perhaps intentional) voter suppression, which led voters in a number of polling places to have difficulty casting ballots. There were problems, in fact, but those problems were bipartisan in effect, hitting blue and red precincts equally.

His lawsuit also points generally to questions about having Hobbs administer an election in which she ran, something that has been raised repeatedly (including by Hobbs’s opponent, Kari Lake). But the Finchem lawsuit, filed with another losing candidate, suggests that Hobbs’s accurate warning to counties that the law required that they certify their election results was somehow an abuse of power.

Now contrast that with how Finchem talks about the election on Twitter.

The real vote was 1.3 million Republican, 1 million Democrat across the board. We all won. pic.twitter.com/0lB7dFmQhO

— Mark Finchem #JustFollowTheLaw VoteFinchem.com (@RealMarkFinchem) December 9, 2022

What this shows, more than anything, is that Republican voters were more skeptical of Finchem than of other candidates, like the losing Republican attorney general candidate (who filed his own suit against the election). Finchem waves this away by suggesting that there was a “real” vote that aligned with how people voted in U.S. House races: 1.3 million for Republicans and 1 million for Democrats.

How this led to his getting 50,000 fewer votes than the Republican running for attorney general or why the state treasurer candidate — who didn’t embrace election denialism — won is left unexplained. But it doesn’t take a lot of digging to see why this claim is better suited for the nonsenseverse of Twitter than in a sworn legal filing.

Quick and easy. Yes, Republican House candidates won 1.3 million votes to about 1 million for Democratic candidates.

But two of those Republicans were running unopposed. Take them out, and the Democrats got about 70,000 more votes.

There were two lopsided wins by Democrats, too. If, for example, you take out Rep. Ruben Gallego’s (D) 55-point victory, then the two parties are about even.

Oh, by the way, the candidate whom Gallego beat by 76,000 votes, a 3 to 1 margin? Jeff Zink, the other candidate who signed on to Finchem’s lawsuit.

Again, this isn’t really new. Kari Lake, the losing gubernatorial candidate, has similarly filed a lawsuit that tries to construct her various allegations and evidence — often anecdotes from supporters who found it harder to vote than they wished — into something palatable to a court. The reason, very simply, is that the court has very little (but not no!) tolerance for deception or invisibly thin evidence. So Lake and Finchem and Donald Trump in 2020 are forced to stuff their vague, incendiary claims into smaller, safer packages. There is sometimes spillover.

The reality is simple. Finchem lost because he ran a bad campaign and held unpopular opinions. He, like Lake, appears to believe that the claims of rampant fraud in 2020 and 2022 were actually legitimate. Luckily for both of them, their lawyers aren’t willing to make the same claim.